Charles T. Williams at Work and Play

- Katie Robinson Edwards

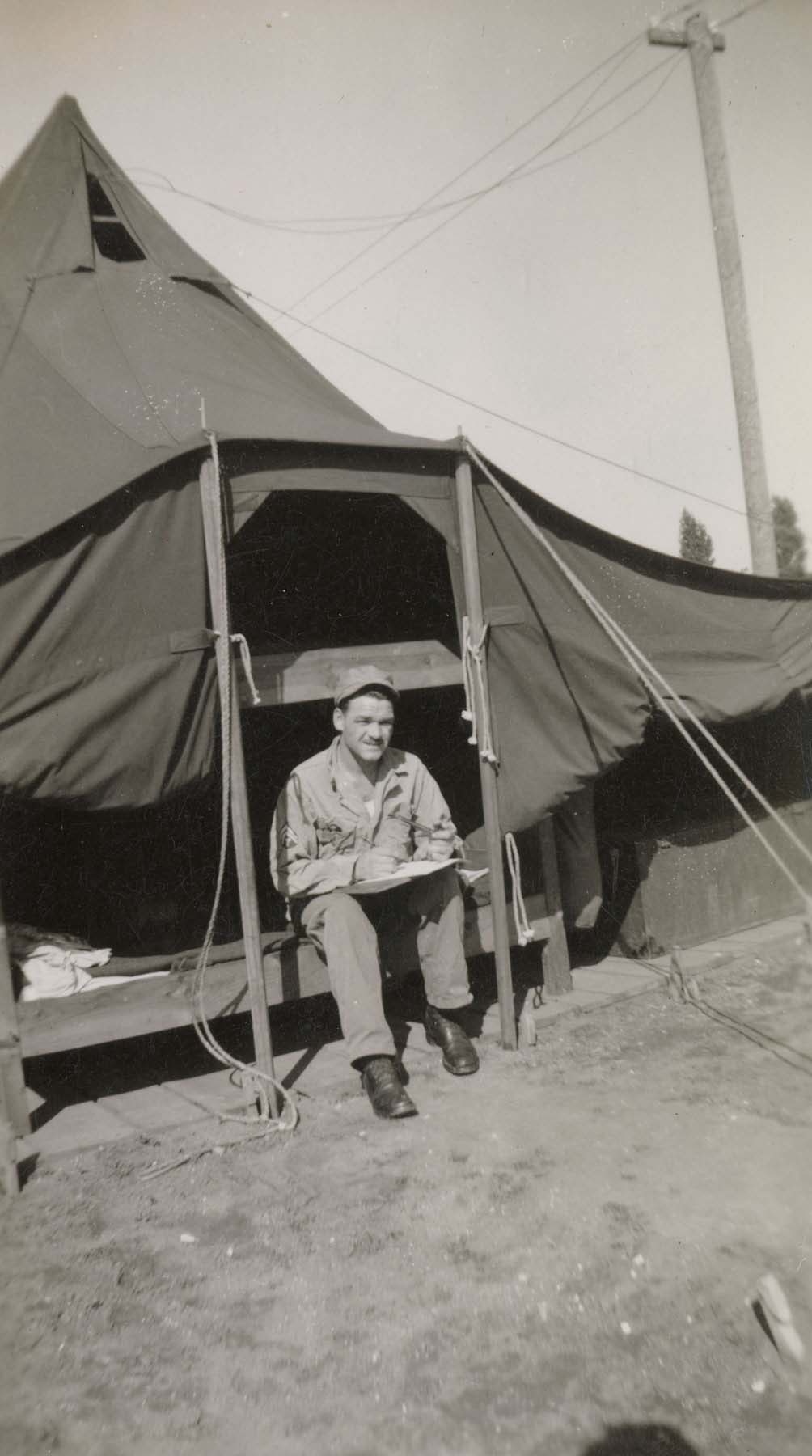

Charles Truett Williams (1918–1966) was rare, even among successful artists, for possessing a single-minded, round-the-clock focus on art. Between February 1945 and June 1946, following the end of World War II, he served a tour of duty in Europe as a topographic draftsman for the Army Corps of Engineers.1 For much of that tour, the twenty-eight-year-old native Texan was stationed in Paris (fig. 3.1). He had been making drawings and cartoons since childhood, and he continued to sketch and create linocut prints while on the transport ship and overseas (fig. 3.2).2 Even when working full time, Williams was like an anthropological participant-observer placed in a foreign land: He watched, researched, and engaged as fully as possible. From the music, the people, the food, the art, and the mood of his surroundings, he absorbed everything with gusto and allowed it to feed his creativity. Whatever aesthetic inclinations Williams brought with him, Paris steeped him in the most current modern art, broadened his mind, and encouraged him to become a career artist.

Upon Williams’s return to the United States in June 1946, he joined his wife, Louise, and their young son, Karl, at their home in Atlanta, Georgia. Tragically, Louise passed away a year later, prompting Williams to move to Fort Worth, Texas, near his parents. There he embarked on a deliberate and decisive path to make his living as a full-time artist. For the next eight years, Williams maintained his job with the Army Corps, raised his son, and completed college and graduate school, all while pursuing his passion of making art.3 Continuing to explore ideas he encountered and developed in Europe, he brought key aspects of both modernism and sociability to the Fort Worth region. Charlie’s shop and Charlie’s studio, as his Fort Worth art studios were known, became literal and figurative watering holes for artists from across the state and beyond.

In 1955 Williams finally quit his salaried job, spending the last decade of his life working full time as an artist. Years later, when asked about his father, his son Karl described him as “an artist all of the time, absolutely all of the time. There was not a moment that that drive ever left him.”4 That drive, along with Williams’s affable character and what a contemporary curator once called his “own special brand of bathroom humor,” made him a central figure who energized the burgeoning Texas modern art scene.5

Williams’s vitality and aesthetic acumen permeated all aspects of his life, infusing a work ethic into his leisure time and a playful spirit into his work life. Play deeply affected his work: Playing games, punning and wordplay, and even play acting all contributed to the artist’s creative output, and similarities and symmetries abound between Williams’s good-natured games and his subsequent sculptures. Fun, humor, games, and sexual innuendo—the jocular liberation of stricture and boundary—occupied a central role in Williams’s art. When he died in Fort Worth at the age of forty-eight, Williams left behind a compelling array of modern sculptures and a legacy as one of Texas’s most creative and unique artists.

Paris: 1945–46

It was work that took Charles T. Williams to Paris, but he found ample opportunities to play. Although Parisians were joyful after the war, four years of Nazi occupation left deep physical and psychological marks; the city and its inhabitants continued to suffer from shortages of housing, power, and food. Williams arrived in Paris in February 1945, six months after the liberation, as part of the postwar rebuilding project led by the US Army Corps of Engineers. Having shown interest in engineering as a student, Private Williams was assigned to the photomapping company attached to the 659th Topographic Mapping Battalion in the Seine Section Headquarters. After regaining territory, the Allies still faced significant obstacles moving into the Rhine region of Germany, including a lack of accurate maps.6 The topographic mapping effort converted aerial photos and other intelligence into functional maps for wayfinding on the ground. At work, Williams learned to make colored topographic maps of Bavaria, prepare multiplex manuscripts from aerial photographs, and ink five-color separation boards.7 He worked side by side with the French, teaching their engineers to do the same. His assignments required him to shift cognitively and physically between two- and three-dimensional spaces. Consciously or not, he acquired crucial pedagogical and technical skills as a result of the rigorous Army Corps training.

We have only the barest of glimpses into Williams’s time in Europe, gleaned from photos, one-sided letters, and recollections housed in the Charles Truett Williams Papers at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. What we see is a man in a foreign land recovering from war, a man obsessed with art and attentive to the aesthetic revolutions of the time, and a man who, throughout all of it, never forgot how to enjoy himself. Like thousands of other American GIs in Paris, Williams took advantage of the locale, traversing the city and countryside to experience many of the world’s greatest cultural and historical monuments and museums. He also found opportunities to meet artists and see paintings and sculptures in person that he had previously only encountered in books and magazines.8 Americans were welcomed as heroes when they helped to liberate Paris in August 1944, and Williams benefited from continued goodwill toward the United States. His tour of duty left an indelible impression, solidifying his resolve and shaping his vision of art and his notion of what an artist was.

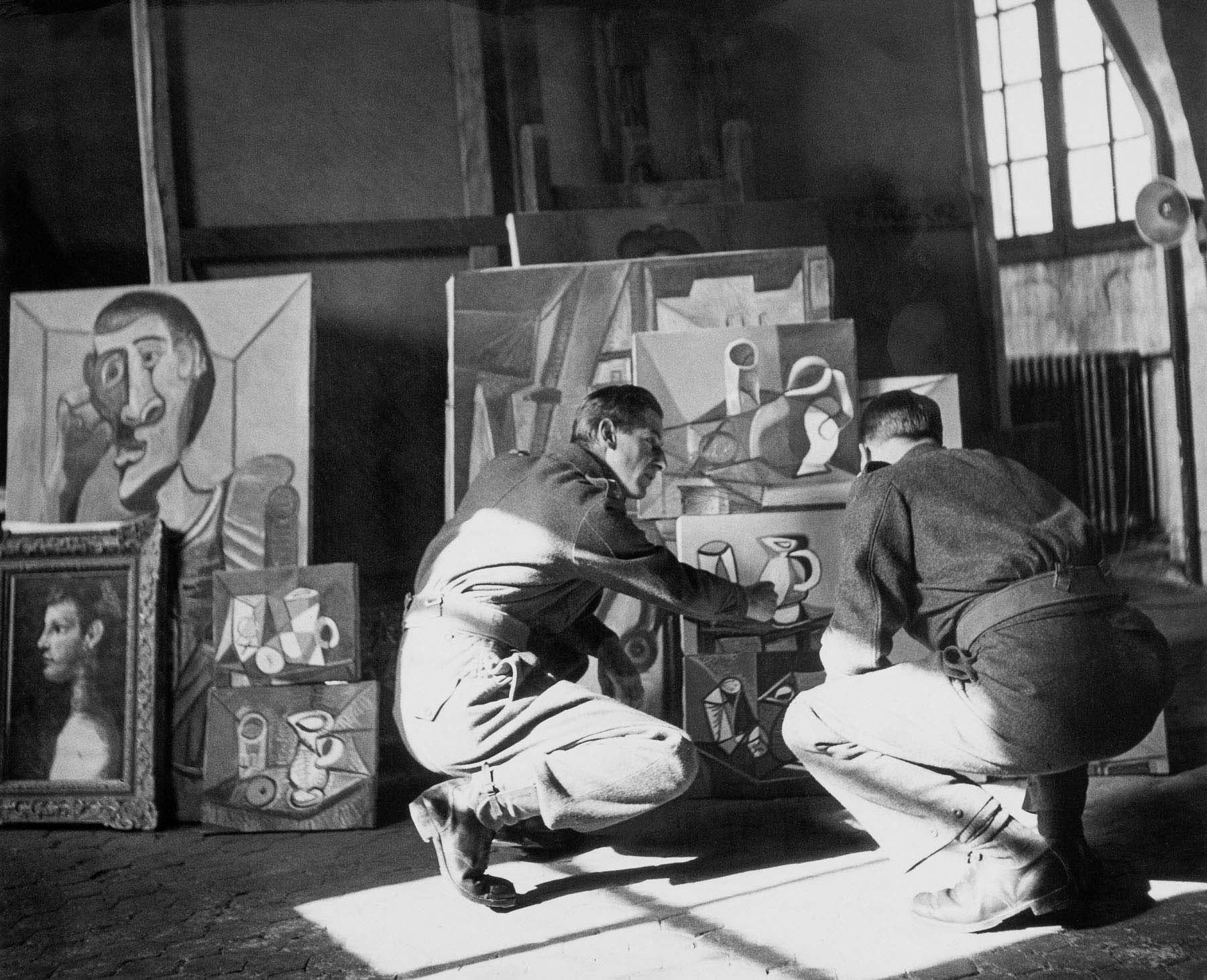

The rise of the Third Reich and the expanding war had driven many artists from Europe, where cities and the countryside were brutally ravaged or completely leveled. Even so, after the German air force bombed Paris in 1940 and killed hundreds of civilians, the Nazis left much of the city intact during their four-year occupation, even as they looted thousands of cultural artifacts. Some prominent artists who fled, like Marc Chagall, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Alberto Giacometti, and Henri Matisse, returned after Paris was liberated. Others, like Constantin Brâncuşi and Georges Braque, remained in their homes and studios for the duration of the war. The Germans allowed Pablo Picasso to stay in his Paris studio throughout the occupation, although the Gestapo periodically paid him visits.9 Like many modern European artists, Picasso was labeled a “degenerate” by the Third Reich, but in the 1940s he was also the world’s most famous living artist.10 Although there is no indication that Williams ever met Picasso, the celebrated artist’s address at 7 Rue des Grands-Augustins was common knowledge among American GIs.11 They dropped in regularly on the Spanish artist, bearing gifts of war rations as Picasso patiently let them wander through his studio (fig. 3.3).12 Germain Viatte, art historian in post-war France and former Pompidou Center Director, noted that, with the war over, “Paris became once more the mecca for artists from all over the world. They arrived to find the heritage of modern art miraculously alive.”13 That heritage included not only historical architecture and artworks but also numerous galleries, museums, and salons that exhibited twentieth-century European modernism.

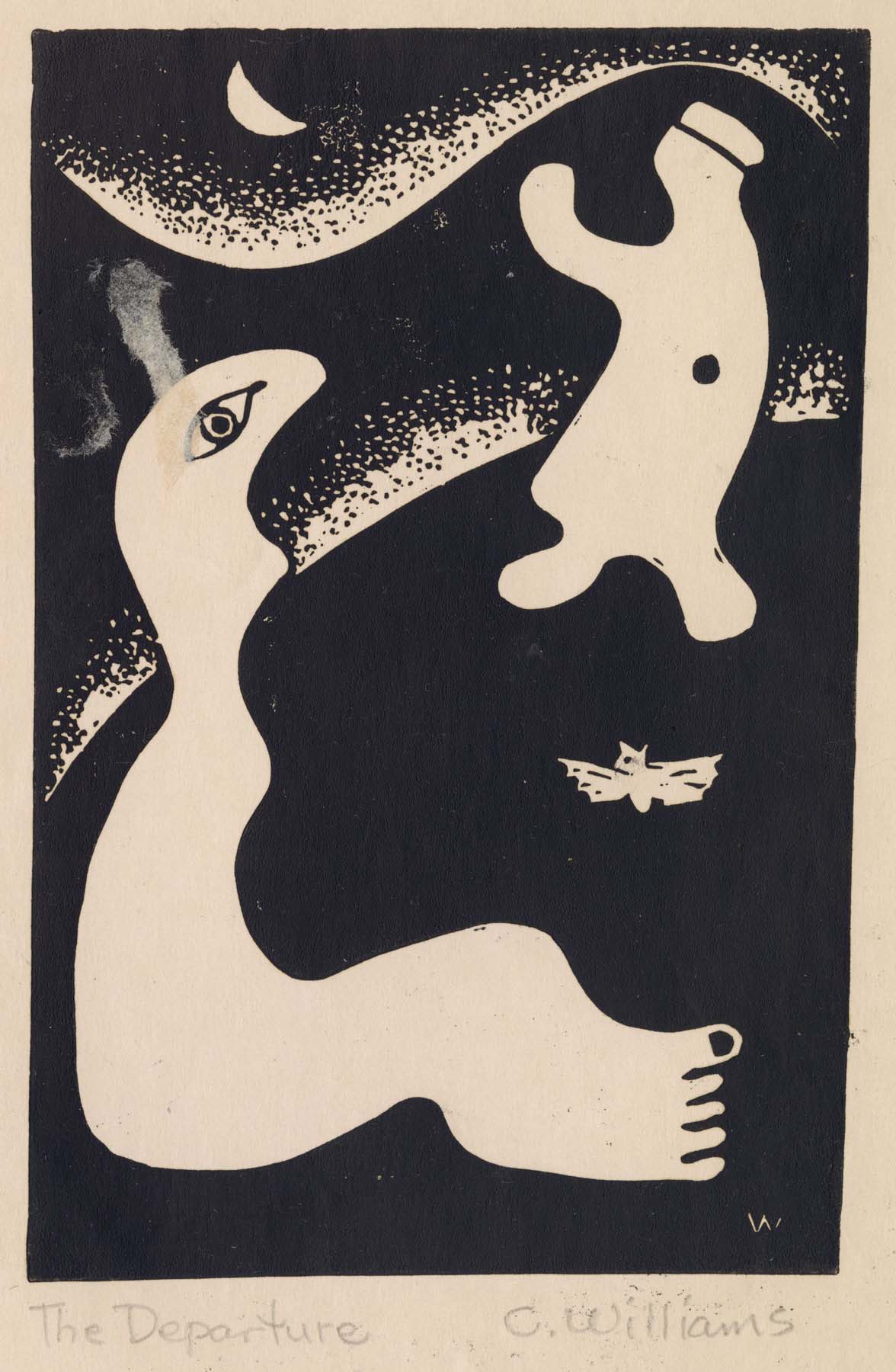

Williams’s art from this period reflects the influence of European artists. Between his full-time Army Corps duties, travels, and socializing, Williams somehow made time to carve and print linoleum blocks. One black-and-white linocut from around 1945 bears a remarkable resemblance to the latest styles in Paris and appears to pay homage to two influential Europeans: author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and artist Joan Miró. The night scene depicts two simple figures—a large, single-footed creature in the foreground and a man wearing a hat, or possibly a crown—both standing on the curved edge of a planet (fig. 3.4). The curve recalls the illustrations in Saint-Exupéry’s 1943 novella The Little Prince. A pilot during the war and national hero, Saint-Exupéry was nevertheless a controversial figure in France. His work had been banned by both the collaborationist Vichy Regime and the French Resistance Movement. His mysterious vanishing on a routine reconnaissance flight mission made global headlines in 1944. Though The Little Prince was published in the United States in 1943, it was not published in France until after liberation in 1945, the same year that Williams arrived in Paris. While the evidence for a direct inspiration is only circumstantial, Williams was tuned in to the French political world as well as the art world; for example, in 1962, he created Portrait of Charles Degaul (misspelled in Williams’s art logbook), a caricature of French general-turned-president Charles de Gaulle, made with a cast iron bathtub leg.14

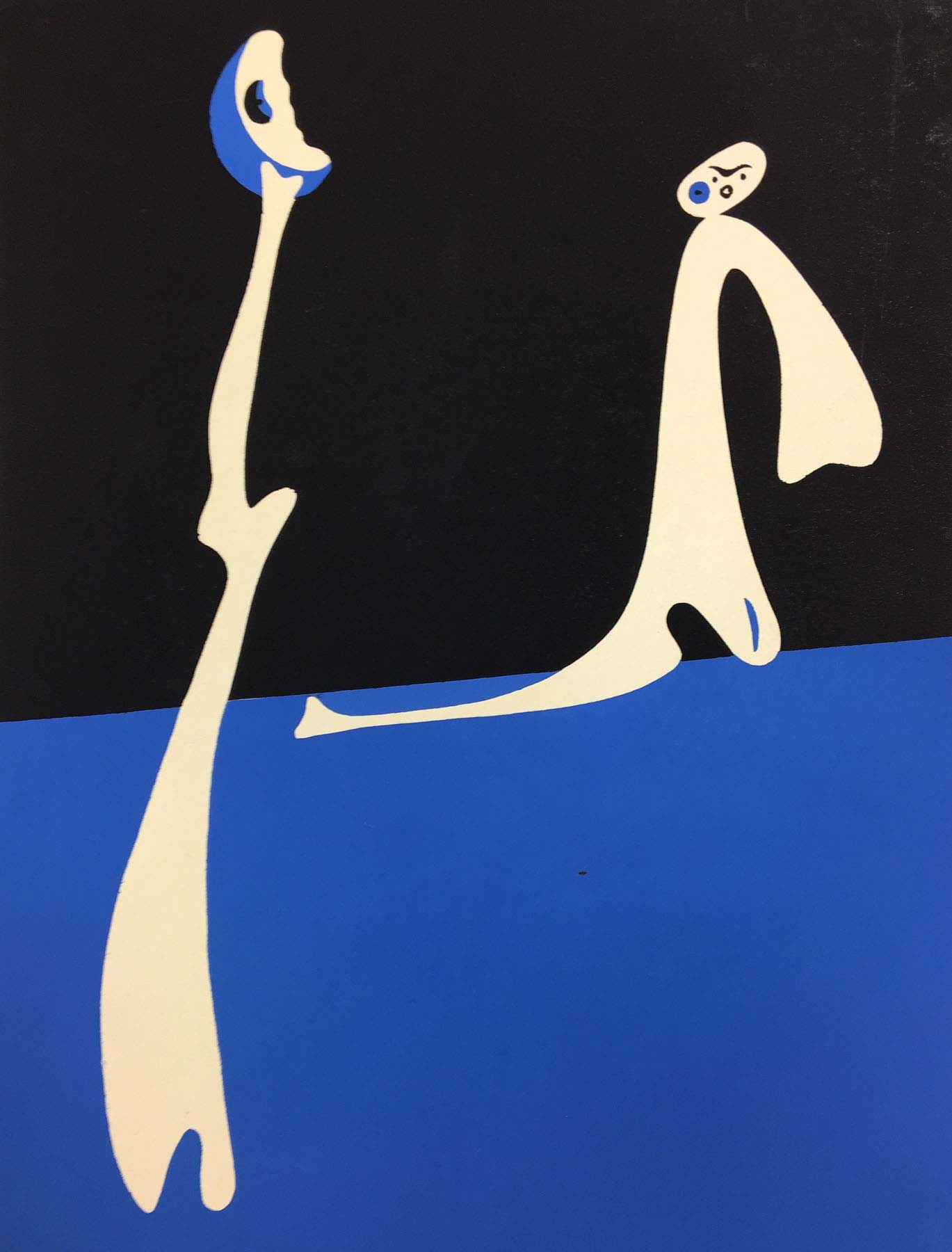

While the setting of Williams’s linocut may take after The Little Prince, the composition visually echoes two works by Catalonian artist Joan Miró. Miró’s 1934 pochoir (or stenciled) print Surrealist Composition II consists of a solid black sky and blue landscape with two elongated, abstracted figures (fig. 3.5). The 1934 edition of the French journal Cahiers d’Art, where Williams may have seen Surrealist Composition II, published in Paris by art critic and collector Christian Zervos, included large-size original colored pochoir prints by Miró. Although neither Miró nor Williams were official members of the surrealist movement, both drew considerable inspiration from its emphasis on “automatic” drawing to access the unconscious mind and the movement’s privileging of elemental shapes and objects.15 An earlier, better known Miró painting, Person Throwing a Stone at a Bird (1924), seems to be another clear source for Williams’s Paris linocut (fig. 3.6). Person features a simplified surrealistic figure characterized by its oversized single foot, set within a bold green and yellow landscape. It is also reminiscent of the cartoon-style, three-dimensional limbs of a pink ceramic figure Williams made after he returned to the United States (fig. 3.7). Whether or not the Texan was familiar with Miró’s work prior to being drafted, in Paris he was impressed enough to emulate the Spanish artist. Williams carried several copies of his linocut back to the United States at the end of his tour.

© Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris 2022. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by Art Resource, NY.

Like Williams, American GIs arriving in mid-1940s Europe encountered art and artists they likely learned about only through magazines and newspapers. Europe was only beginning to recover from the war’s devastation, and the exodus of artists had initiated the art world’s shift to New York City. Still, from 1945 and for several years after, again according to Germain Viatte, “Paris was the only major capital cosmopolitan and receptive enough to become the focus and the promoter of new ideas.”16 The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, nicknamed the GI Bill, ensured the US government would fund classes for soldiers who had served at least three months in the armed forces.17 For example, over a hundred American servicemen-artists enrolled in regular lessons at the studio of Picasso’s colleague, the French painter and sculptor Fernand Léger.18 It is important to note that generally speaking, American GIs, many of whom were young and came from small towns or rural regions, might not have had the sophistication or awareness to know that Paris was in the process of losing its title of art world capital. In short, it didn’t matter much to them: the City of Light may have been dimmed, but to Americans it was a spectacular, culturally rich metropolis. Themes of revolution, thwarting the system, and rebelling against academicism ran deep in the local psyche, and Paris retained its well-earned, if waning, reputation as the center of European modern art.

In fact modern art itself was born in Paris. One can even pinpoint a particular year: 1863, when French painter Édouard Manet displayed his scandalous painting Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe at the Salon des Refusés, the exhibition of artworks rejected from the official French Salon. Manet depicted two fashionably dressed men sharing a picnic on the grass with a nude woman who confronts the viewer with her brown eyes and starkly painted pale face. Exhibition visitors recognized the naked woman as a prostitute and the illicit scene as taking place on the outskirts of Paris in the fashionable Bois de Boulogne area.19 With Le Déjeuner, Manet marked the beginning of a long series of challenges to the status quo and of intentional transgressions by artists of aesthetic and cultural boundaries. During the following decade, Claude Monet and a group of artists painted outdoors, translating the effects of changing light into color, placing quickly rendered brushstrokes onto their canvases and forever altering the concept of what a finished painting could look like. Scathingly dubbed “Impressionism” by a critic who visited their 1874 exhibition, a new art movement was born.

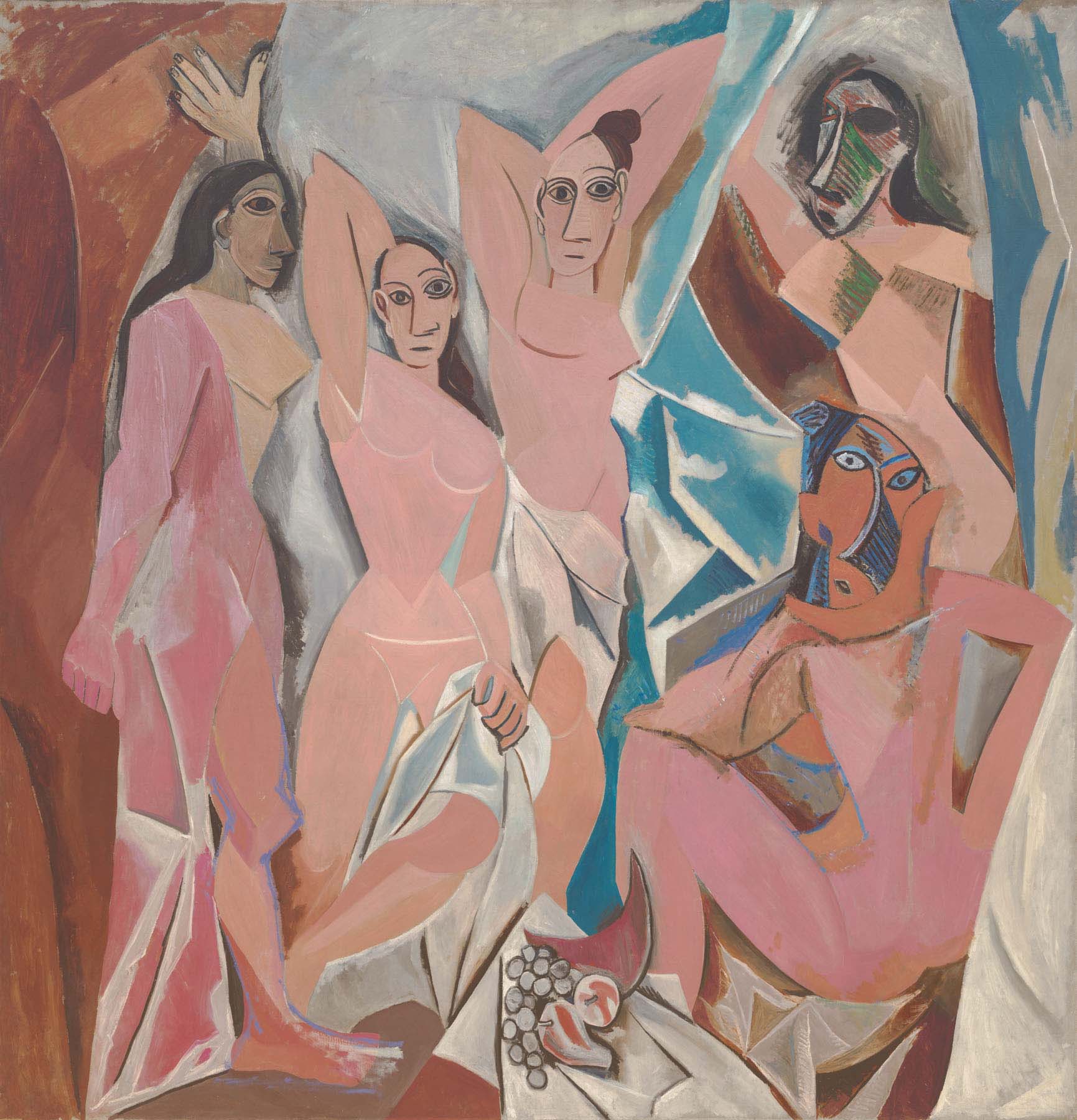

In 1907, Picasso turned tradition and decorum on its head once again when he finished his grand eight-by-eight-foot canvas Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, a depiction of five nude female figures in a Barcelona brothel (fig. 3.8). By intentionally rivaling the monumental scale of traditional French academic paintings, Picasso made it impossible to ignore his decidedly confrontational figures. Flattening the planes of the women’s angular bodies and reinterpreting their volume through deliberately visible shade marks, Picasso embarked on the road to cubism. Notably, he also painted two of the women wearing what appear to be African tribal masks.20 Historians believe this gesture reflected his visits to the artifacts in the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, later known as the Musée de l’Homme.21 Dedicated to the study of ethnography and anthropology, the Trocadéro’s collection of tribal objects and so-called “primitive” art influenced Picasso and many other early twentieth-century cubist and fauve artists.22

As a result of European colonization in the African continent and throughout Oceania during the early twentieth century, art from these cultures flooded Paris markets and galleries, ripped out of their original contexts. Picasso was not alone; the imagery and iconography of Oceania, Iberia, Mesoamerica, and Africa was repeatedly borrowed by artists, Williams included. Through appropriation, artists challenged European social norms and standards of “high art” while they simultaneously reinforced negative colonial stereotypes about non-European peoples. Many European and American artists genuinely resonated with the power conveyed in tribal objects, as Picasso claimed to have done, but artists also sought to utilize the subversive potential and shock value of objects that upset Western standards. These appropriations decisively changed the course of modern art. However much Picasso may have known about Africa and Oceania, he sensed that the objects he saw had little to do with aesthetics (a distinctively European invention) and instead served a “sacred, magical purpose.”23 Recognizing the significance of Picasso’s proto-cubist accomplishment, in 1939 New York’s Museum of Modern Art purchased Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. The painting, complete with its African and Iberian influences and tawdry setting, became a touchstone for contemporary artists and by 1946 was firmly ensconced within the modern art canon.24

Although Williams could not have seen Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in France, examples of non-European art would have been discoverable throughout Paris. It is likely that the young Texan’s perambulations, coupled with his interest in the artistic legacies of the city, led him to explore non-western art in Paris, perhaps even carrying him to the Musée de l’Homme. (His Parisian girlfriend, Lîlà, discussed at length below, also happened to live nearby.)25 According to the artist and writer Tom Motley, Williams “was intrigued with tribal ritual masks of Polynesia, in particular with the emphatic sense of character illustrated in those of New Guinea.”26 Black-and-white photographs from the Williams archive that date to his time show that he owned an Oceanic or African-style mask and two other non-Western sculptures.27 The origins of these objects, and whether they are authentic artifacts or replicas, is unknown.28 But they were important enough to Williams that he kept them his entire life, nicknaming the male mask “Joe” and the female figure “Rosie.” Indeed, these experiences and collections must have left quite an impression on Williams: Fifteen years after returning to the United States, he welded together the African-inspired Ubangi Woman from scrap salvaged from Gachman Metals in Fort Worth (fig. 3.9).29

Gregarious and hungry for life, Williams absorbed Parisian culture like a sponge. The artist’s 1946 datebook contains only abbreviated references to various activities and locales, providing an incomplete but nonetheless rich picture of his exploits in Paris. He writes of going to horse races at the Longchamp Hippodrome in the Bois de Boulogne; another time he watches the races at the Saint-Cloud Hippodrome.30 He makes notes of various dinners (“had chow at Monde/l”) and outings, sometimes geographically far from where he was stationed. He toured historical sites: Three times during February 1946 he visited the ancient Roman road that became the Rue du Faubourg-Montmartre.31 Some agenda entries allude to gaming activities (a “Ping Pong Bar”) or pure entertainment (a “movie”).32 He also partook of highbrow art forms. At least twice he patronized the Paris Opera at the famed Palais Garnier. He adored the ballet, attending in October and November 1945, and then at least three times in March 1946. In a letter to his wife back home he wrote:

Ballet to me is the height of emotional expression. I love it. Wish I could see one every day. Think I’ll go back and see this one again. It’s an English troupe and damned good if they are a little conservative. I love you.33

Louise’s responses to her husband’s letters have not survived, but Williams seems at ease sharing with her, apparently confident of her positive response. (Other deployed servicemen might have shied away from telling their wives how much they loved ballet.) Although the biographical record on Louise Williams is scant, she was no stranger to theater, having written, produced, and directed her own radio show in Atlanta, the Louise Williams Drama Hour.34 After Charles’s discharge, it is unknown whether he and Louise ever went to a ballet during their brief reunion in Atlanta. Once he moved to Fort Worth, however, Williams befriended artists of the Fort Worth Circle, who shared his passion for ballet, even performing their own dances and gifting one another ballet slippers at Christmastime.35

Photographs in the Williams archive show that while in France he traveled to landmarks including the Arc de Triomphe, the Dôme des Invalides, the Louvre, Notre Dame de Paris, the Palais de Justice de Paris, Place Vendôme, the Tombeau du Maréchal Foch, and Versailles, as well as unrecognizable sites of bombed-out architecture.36 He snapped pictures of Parisian markets, American soldiers, and German guards. These photos often display a sly, slightly bawdy sense of humor as well as a keen attention to detail. On one of his walks through the city he photographed a pigeon standing on the edge of a circular cast iron tree grate after a rain (fig. 3.10). One can imagine how the engineer in Williams admired the industrial design of the protective grate and the way it allowed water to reach the tree, or perhaps how he saw the pigeon as peaceful, comical, or all of the above. On the back of a snapshot of a young French woman in a dress riding a bicycle, Williams wrote, “Mademoselle [sic] on Champs Elysees / the skirts didn’t blow as per usual.” In still another photograph, this one by someone else, Williams stands in a public urinal plastered with broadsides, looking back at the camera (fig. 3.11). In an ominous reminder of the times, a poster on the latrine wall announces, “Un Document sensationelle: Le Carnet de Notes d’Hermann Goering,” opening June 6.37 On the verso Williams noted, “Me in typical French latrine Paris France Aug ’45.” The juxtaposition of the Texan relieving himself next to a symbol of German atrocities is revealing: While it indicates Williams’s ability to use scatological humor to create levity in challenging times, it also symbolizes the plight of thousands of young American soldiers who were deployed across Europe impossibly ill-equipped to handle the tragedy of the Holocaust and the war.

Something else Williams had in common with many American soldiers overseas was that, despite having a wife and son in the United States, he passed the time with a European girlfriend.38 Whether out of fear that they might never return home or as a result of being caught up in the romance of Europe, soldiers routinely engaged in sexual relations with locals. In fact, such dalliances may have been inadvertently encouraged by the paternalistic military culture. Historian Mary Louise Roberts maintains:

[World War II] was a particularly eroticized war. Anybody who remembers the pinups on airplanes, Rita Hayworth, the amount to which pinups became a part of the culture of the GIs, will recognize to what extent sex became important to the war experience. . . . Photojournalism in particular was used to portray the Frenchwoman as ready to be rescued, ready to greet the American soldier, and ready to congratulate and thank him through a kiss or even more.39

The subject of servicemen’s intimate relations seems unwholesome, standing in contrast with our received notions of American heroism in World War II.

Unlike some of his fellow soldiers, Williams seems to have had sustained relations with only one woman, Giséle Ménard, also known as Mrs. Lîlá Lippens. There is no indication of how they first met or whether Williams’s wife Louise knew about Lîlá. What evidence we have of their amorous relationship is gleaned from letters Lîlá wrote him after he left Paris, many of which are preserved in the Williams archive. (Regrettably, we only have Lîlá’s letters that Williams saved but no letters Williams sent to her.) Her dispatches arrived regularly for months in 1947 and intermittently thereafter: They indicate that he mailed her numerous letters and parcels, though evidently not frequently enough for Lîlá to be satisfied. For example, in a 1948 letter she wrote, “I’m developing a turned down nose, a turned down mouth, and a suspicious belligerent eye. The disappointment of having no mail from Fort Worth give [sic] me a MEAN look, a kind of death ray look looking for you.”40

An entrepreneur and great appreciator of the arts, Lîlá came from a wealthy family, spoke at least three languages, and traveled regularly throughout Europe and India, eventually establishing a successful import business. She occasionally made self-conscious fun of her limitations when writing in English, yet her judicious use of English words is at moments utterly disarming. We can surmise that Williams was charmed by her accented English and careful diction. (He valued verbal puns and whimsical titles and maintained a running list of potential artwork titles, both serious and comical, at the back of his sculpture log.) At one point in their correspondence, Williams must have inquired as to whether Lîlá was “still single.” Her answer came, unequivocal and shrewd: “OF COURSE, I’m single, and not like you ‘so to speak.’ I’m single, period.”41

However one views their romantic affair, Lîlá was unquestionably one of the artist’s greatest supporters and champions of his art making. Her correspondence reflects intense interactions about art, books, people, and love that they shared during their time together. One letter included a photo that Charlie (as she calls him) must have mailed her, of him with their mutual friend “Mac” at Harry’s New York Bar in Paris. (Perhaps “Mac” was the nickname for the establishment’s owner, Harry MacElhone, discussed later in this essay.) Elsewhere she thanks Williams for a package that contained coffee and powdered milk—Borden’s brand—two staples Lîlá was unable to obtain in postwar Paris. At another point, she mailed him a box of Edith Piaf records that we know he played on the turntable in his Fort Worth studio. Early in 1947 Williams must have sent her a ceramic sculpture that he made and fired in Atlanta. She responded, “My love, listen closely, I got big plans for your ceramics.”42 Later, in February 1948, she wrote of having received a box that included colored ceramic buttons and being “most excited to wear ‘your’ buttons.”43 She asked Charlie to “Tell me more about your future shop” and enthusiastically praised his work after he began to exhibit publicly in Fort Worth, writing at one point, “Figures in plaster at Fort Worth exhibition!”44 Perhaps prophetically and in a sly elision of sculpture and sensuality, in 1947 she wrote to Williams: “I got to think of your hands—you got the right hands for sculpture—ceramic is one thing. Sculpture is another. Why don’t you try to keep on with both—I wish you try doing my head, for instance.”45

For several years, both seemed to think that one day they could reunite: She mentioned marriage, repeatedly invited him to live with her, and indicated she would inherit a great sum of money once her father passed away. Although we do not have Williams’s responses, a few months after Louise’s death, he applied for US Government employment requesting an assignment (likely it would have been another transfer within the Army Corps of Engineers) in Austria or Germany.46 As the years passed, they remained friends even after each of them remarried different people.47 Nearly twenty years after their war-time affair, in 1963 Williams and his then-wife Anita visited Lîlá in Europe. And in 1966, in an indication of the former lovers’ cultural and class differences, Lîlá mailed the Williams family an elegantly typeset card announcing her divorce.48 Sadly, it seems to have been the last piece of correspondence he ever received from her.

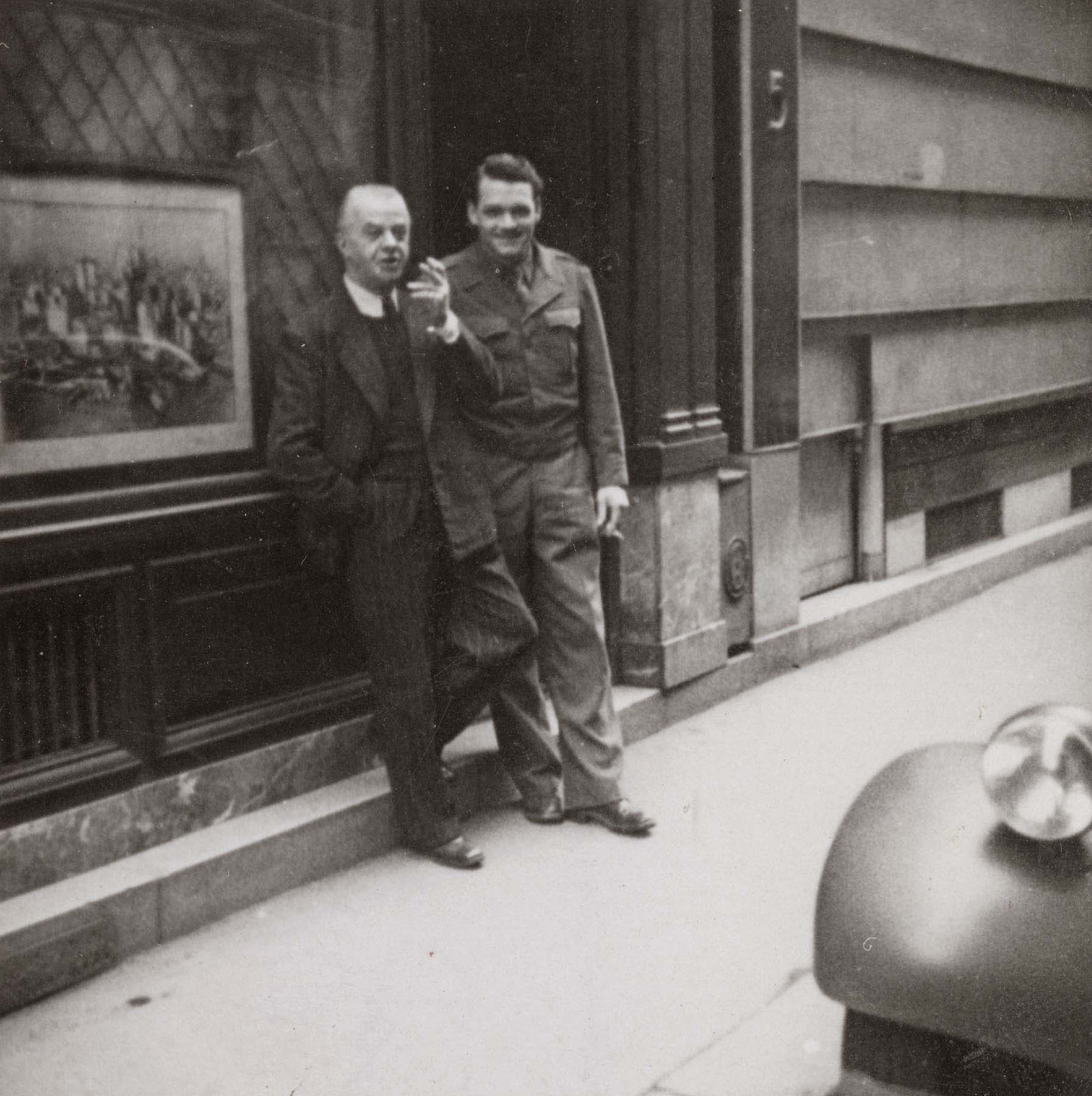

In Paris, one of the venues Williams and Lîlá frequented together was the aforementioned Harry’s New York Bar, the renowned expatriate hangout located near the Opera and the Place Vendôme at 5 Rue Daunou. Williams quickly found Harry’s to be a home away from home. Everything about the bar would have suited the Texan’s tastes: the buoyant atmosphere enhanced by cigarettes and alcohol, the constant flow of American expatriate, French, and foreign travelers, the women displaying current Parisian fashion, the opportunity to discuss every kind of cultural and political event, the prime location in a key cultural district of Paris, and the respite it provided from the anxiety brought on by trying to reconstruct entire nations after the war.

Harry’s Bar represented a literal piece of Americana in Paris: The establishment was named for the carved mahogany bar that Harry’s original owner shipped across the Atlantic from New York’s Seventh Avenue pub district around 1910 and then reassembled in Paris.49 Among the bar’s most famous denizens were actors Humphrey Bogart and Rita Hayworth; authors F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Sinclair Lewis; and football legend Knute Rockne. A regular, Williams went alone, with his army buddies or other acquaintances, or with Lîlá. He became good friends with the bar’s namesake, Scotsman Harry MacElhone, exchanging photographs and Christmas cards even after Williams returned to the States (fig. 3.12).50 Sometimes they carried on their socializing away from Harry’s Bar: One Saturday in May 1945, Williams, Harry, and Lîlá had a night out in the bohemian Montparnasse neighborhood.51 The engaging Williams would have struck up conversations with numerous customers, sharpening his conversational skills while learning about wide-ranging aspects of life abroad. He met all kinds of people, including businessmen in postwar Paris who were taking advantage of newly reopened European markets, like the American Ray Rivington Powers, who headed the Coca-Cola Company for the entire continent. As Williams reported in a letter home to Louise in Atlanta, he found Powers to be “a nice drunken character.”52

Williams also met the American author Henry Miller at Harry’s Bar and at some point acquired a signed copy of Tropic of Cancer, Miller’s quasi-autobiographical novel filled with candid accounts of sexual exploits drawn from his expatriate life in Paris. Published in 1934 by the English-language Parisian imprint Obelisk Press, both Tropic of Cancer and its prequel, Tropic of Capricorn (published 1939), drew charges of pornography and were banned in the United States.53 Although Williams was friendly and open to new ideas, he hailed from a conservative, rural Texas background. Having broken sexual mores and boundaries himself, one can only imagine how Miller’s novels and meeting the author in person affected Williams at that crucial point in his life. The two men maintained a friendship after their returns to the United States, with Williams visiting Miller on a trip to California in the late 1950s.54

Years later, sculptor Gene Owens, who became one of Williams’s closest friends, recalled how Williams enjoyed showing off his collection of mimeographed booklets that Miller allegedly traded for drinks at Harry’s Bar.55 Owens laughingly remembered another of the artist’s oft-told stories: Williams evidently spent so much time at the bar that the managers gifted him a lapel pin of a fly made of solid gold and colored enamel. Indeed, among the Williams papers are documents referencing the “Order of the Barflies” at Harry’s.56 Owens said Williams was fond of telling people it was the only medal he received during the war.57 Harry’s New York Bar possessed a lively and creatively charged postwar joie de vivre that was not lost on Williams.

From Atlanta to Fort Worth

In June 1946, after crossing the Atlantic on the USNS Aiken Victory transport ship, Williams reunited with his family in Atlanta, Georgia.58 Back on familiar ground, still working for the corps, and buoyed by all he had seen and heard in Europe, his art career began to blossom. He tried to educate himself with the latest information on pottery and glazes (fig. 3.13). At the Atlanta library he checked out A.L. Hetherington’s Chinese Ceramic Glazes (1937) and R. Horace Jenkins’s recently published Practical Pottery for Craftsmen and Students.59 According to his tiny agenda book (which he carried back from Paris), in September Williams sought “books and plaster” and made a note about “buttons, kiln, glazes, blueprint of plaster mixture.” He became acquainted with an assistant professor at the Department of Ceramic Engineering at the Georgia School of Technology named W. Carey Hansard. They met on more than one occasion, discussing kilns and presumably glazes.60 Williams made and fired ceramic figures, such as the small, emerald-green seated female figure who reclines with her head cradled in her uplifted hands, like a three-dimensional interpretation of a Matisse odalisque (fig. 3.14).61

This flurry of activity came to a halt just over a year later when Williams’s wife, Louise, whom he had known since college in Abilene, Texas, died unexpectedly from viral pneumonia. Devastated and alone, with a five-year-old son, Williams left Atlanta for good in 1947 to move closer to his family. He was able to transfer to the Corps of Engineers in Dallas and live with his parents in Fort Worth. Charles’s lifelong friend George Fortenberry, who had known the Williams family since they lived in Mineral Wells, Texas, in the 1930s, suspected the new living arrangements would prove challenging: “Mrs. [T.L.] Williams was a grimly determined Baptist who had named her son for a Dallas evangelist and had actually tried to dedicate his life to the ministry.”62 By contrast, her son Charles was not a practicing Baptist, had named his only son for Karl Marx, and sketched and sculpted from live nude models. (Williams was irreverent, and art was his religion. For example, he titled a woodcut print of a modernistic abstract male and female figure, with a Henry Moore-like hole in the man’s arm, Immaculate Conception.) But it must have worked, as Fortenberry wryly observed, because Charles Williams became “a religiously dedicated artist.”63

The upheaval proved fortuitous, as Fort Worth turned out to be an ideal crucible for Williams and his unwavering determination to make art. First, he was able to stabilize his domestic life, and his family helped him care for his young son. He also found his lifelong partner: Within a few years of arriving in Fort Worth, Williams fell in love with and married Anita Stuart McConnell, whom he met when she was Karl’s third grade teacher. Anita and Charles became a dual income family, likely helping Williams retain the freedom to choose what kind of art he created.64 Equally important, his responsibilities with the Army Corps in Dallas built on his intensive training in Europe, increasing his drafting and engineering knowledge and priming him to easily visualize and fabricate drawings and sculpture. These skills provided the grounding for his more complex projects, such as devising the mechanics of the outdoor fountain commissioned by collectors Ted and Lucile Weiner in 1955.65 Additionally, his father, T.L. Williams, and brother, Joe, ran a successful construction business in the region.66 Charles had worked with both of them briefly in the 1930s.67 Even if his family might not have understood his decision to be an artist, Charles gained access through them to contractors, vendors, and the latest technology that he used in his art business.

Finally, Williams discovered a group of established Texas artists, known today as the Fort Worth Circle. Their roots could be traced back to the Fort Worth School of Fine Arts, founded by Sallie Gillespie, Blanche McVeigh, and Evaline Sellors and opened in October 1932 (under its original name, The Texas School of Art). McVeigh and Sellors are credited with organizing Fort Worth’s earliest exhibitions of modern European art, borrowing objects from private collections. Historian Scott Grant Barker has pointed out that their exhibitions marked the first time that works by Brâncuși, André Derain, Fernand Léger, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Picasso, Maurice Utrillo, and other European modernists were publicly shown to a Fort Worth audience.68

The members of the Fort Worth Circle were a progressive, cosmopolitan group that shared Williams’s interest in art, classical music, ballet, and theater. They were influenced by, and attentive to, European modernism and especially the School of Paris, including both the cubist and surrealist branches. Many—including Sellors and husband and wife Dickson Reeder and Flora Blanc Reeder—had formal training from art schools on the East Coast or in Paris. As most of the participants were a few years older than Williams, they also provided him with a blueprint for an art career. They had been exhibiting publicly for years, including in an important 1944 group show in New York where a critic identified them as a “compatible and independent-minded group.”69 In the 1940s, the Reeders hosted European-style salons at their Fort Worth home. In the 1950s, the Reeder Children’s School of Theater and Design was in its heyday, staging numerous productions. According to Scott Grant Barker, “Each year the Reeders recruited not only many local artists to work on their elaborate productions, but they also brought in actors to work as dramatic coaches, professional musicians to form an orchestra when required, and professional dancers to train the kids. Charles Williams, Ann and Jack Boynton, Sandra and McKie Trotter, and John Erickson were all credited as volunteers on the 1952 production of The Happy Hypocrite.”70 By about 1960, the social locus in Fort Worth had shifted entirely to Williams’s studio, where Charlie and Anita held countless soirees and many impromptu gatherings.

Williams built his first dedicated art studio in the double garage behind his family’s house at 4723 El Campo in Fort Worth, a space that came to be called “Charlie’s shop.”71 By the spring of 1948, he had enrolled in night school at Texas Christian University (TCU) and by 1952 had earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree.72 Initially, the core participants at Charlie’s shop were TCU students and professors and the slightly older Fort Worth Circle generation. As an army veteran and an older student, Williams was nearer in age to his TCU professors, like John W. (Jack) Erickson, who became a lifelong friend. He quickly struck up a friendship with fellow student James (Jack) Boynton. Although Boynton was ten years younger, they remained best friends for the rest of Williams’s life.73 Boynton knew he was part of something special, later recalling, “We were sort of the avant-garde of Fort Worth at that moment.”74

He remembered the older artist’s energy, enthusiasm, and generosity toward other artists in those years and how Charlie rode the bus to work in Dallas each day, returning to Fort Worth to work “half the night on sculpture.”75 Boynton called Williams “the most patient man I ever saw,” especially when it came to nurturing younger artists like himself.76 In 1960, Boynton gifted Williams a wooden sculpture featuring three square shaped heads, made of blocks of wood, nestled inside a hinged wooden box. The title is Captive Audience (pl. 17). The central mustachioed head inside the box bears a telltale resemblance to Charlie. The flanking “blockheads” may represent Boynton himself and their good friend, the artist Jim Love.

Boynton fondly described how friends and guests came through Charlie’s shop at all hours of the day and night, making it feel like “Grand Central Station every day.”77 Around this time, Williams received a letter from his European girlfriend, Lîlá, who expressed dismay at his frenetic work schedule and commute: “[You are] riding 3 (hrs) a day to come and go from your job. . . . I hate to think you’re wasting 3 hours a day you could use for ceramic [sic] or just to recuperate.”78 Even from across the Atlantic, Lîlá continued to ruminate about Williams’s artistic welfare and career.

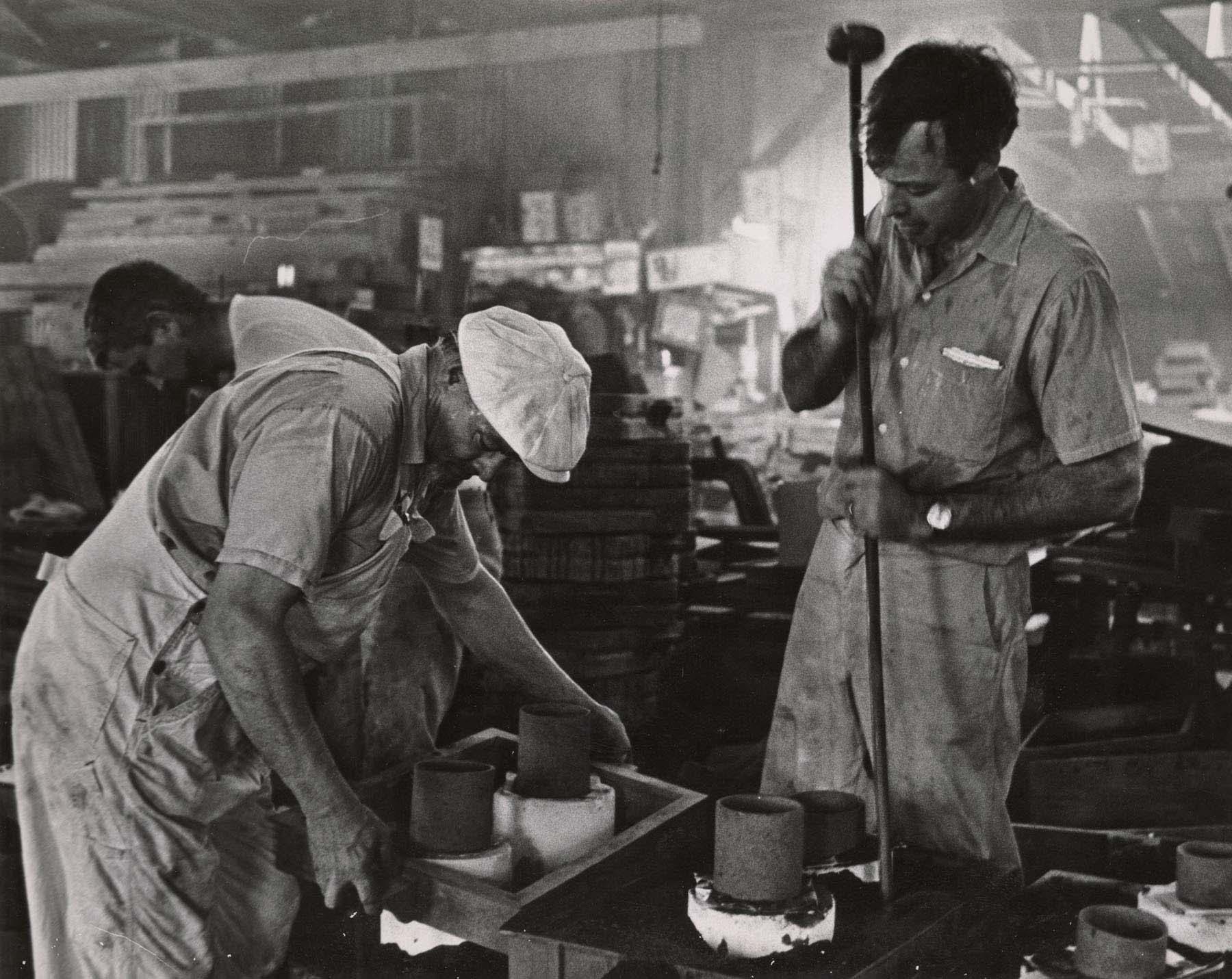

Gene Owens, another of Williams’s many friends in Fort Worth, first met Williams in 1951 while Owens was in a Texas Wesleyan College undergraduate course taught by painter McKie Trotter. Trotter often took his art students to visit Williams to show them how “a real sculptor” operated.79 Over the years Owens dedicated countless hours in the studio and foundry with Williams (fig. 3.15), where he produced works like Cinder Sun (fig. 3.16). Like Williams, Owens did not adhere strongly to the Christian faith with which he was raised. Unlike Williams, he developed a fascination with ancient Greek, Eastern, and South Asian deities and religions that he incorporated into his art. Yet both artists shared a belief that the bronze casting process itself was somewhat transcendental.

Owens recalls countless tales about Williams, including one that conveyed the older artist’s irreverence toward religion, or more particularly, “Holy Roller” religion when it disrupted his work.80 As Owens tells it, one night a religious group installed a revival tent on the empty land right behind Charlie’s studio. The churchgoers created a ruckus that went on into the wee hours of the morning. After tolerating it for a few hours, Williams, wearing his workman’s overalls and carrying his trademark gold cigarette holder, left his shop to see what was going on. In the tent he found two women lying on the sawdust floor “kicking and screaming and hollering.” Owens wanted nothing to do with it so remained near the back of the tent. Williams walked down the aisle, smoking his cigarette and looking from side to side at the congregation. He approached one of the women on the floor, then looked up at the preacher, who told him, “Mister, you’re interfering with the Lord’s work.” Williams took another puff of his cigarette and replied, “The Lord’s work? Hell, I thought it was the Devil’s!”81

Such was the energy at Charlie’s place that visiting it became de rigueur for anyone in the area who was interested in contemporary art. Williams himself served as catalyst, his studio as the “social center,” according to the artist Roger Winter.82 Williams remained in his studio on El Campo until 1952, when he moved to his second studio, southeast of town near what is today Highway 820 and Sun Valley Road. The list of studio visitors reads like a who’s who of the regional art scene: Heri Bartscht, Jack Boynton and his wife Ann Williams Boynton, David Brownlow, Bob and D’Aun Cunningham, Jane Cunningham, Jack and Jane Erickson, Kelly Fearing, Roy Fridge, Duayne Hatchett, Jim Love, David McManaway, Gene Owens, Dickson and Flora Reeder, Evaline Sellors, Emily Guthrie Smith, Ed Storms, McKie Trotter, Bror Utter, and Donald Vogel. They rubbed shoulders with friends, gallerists, and local luminaries like Dallas Museum of Art Director Jerry Bywaters, Fort Worth Art Center Director Henry Caldwell, Fort Worth Art Association President Sam Cantey III, Fort Worth Art Association Director Dan Defenbacher, actors and musicians Dick Harris and his wife Georgie, Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts Director Douglas MacAgy, Neiman Marcus president and arts patron Stanley Marcus, patron and gallerist Betty [Brooke] McLean Blake, and collectors such as Raymond Nasher and Ted and Lucile Weiner. When they came to Texas to install or speak about art or architecture, Buckminster Fuller, Claes Oldenburg, and Isamu Noguchi each stopped in.83 At the center of the scene were the gracious and generous hosts, Charles T. Williams and his beautiful, patient, and witty wife, Anita.84

Canadian curator Douglas MacAgy was an example of the type of savvy, art world-pedigreed interlocutor with whom Williams engaged in North Texas. MacAgy trained in London and Pennsylvania, revitalized the California School of Fine Arts by embracing abstraction (and bringing both Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still to teach there), served as a special consultant to the director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and was, from 1959–63, director of the Dallas Museum of Contemporary Art.85 A decade later he wrote about his time in Dallas: “As an artist, a man with swinging curiosity and surprise perceptions, as a generous friend and relaxing host, the late Charles Williams was a key figure in bringing most of the rest together. . . . Again and again, Charlie’s new and older friends were drawn to his and Anita’s memorable parties.”86 Between the TCU cohort, the Fort Worth Circle artists, and the Dallas contingent, Williams found people in Texas with whom he could truly relate.

At Charlie’s studio, art making and merrymaking went hand in hand. Conversations went on at all hours, fueled by martinis, beer, and cigarettes.87 Williams seems to have internalized both lessons and an artistic ambiance from his European sojourn. The romance of Paris stuck with him, instilling a desire to recreate both the sociability and the artistic productivity in his new town. A close examination of some of the archival documents in the Williams Papers provides insight into Williams’s artistic practice and how he transformed social occasions into working parties, and vice versa, with a unique, European-inflected flair.

The concept of play itself was embedded in a paper-and-pencil parlor game that visitors to Williams’s studio played regularly. Nicknamed “The Game,” the rules were simple enough that any guest could partake: One person drew three basic lines on a sheet of paper, invented a title, and passed the paper to a partner. Using those three lines, the second person created a drawing to illustrate the title. The results were relatively quickly dashed off. It was easy enough to play even after a few drinks; indeed, the martinis and beer surely contributed to the creative flow. The Game was an icebreaker, an amusement, a form of entertainment, and never intended to create fine or finished works of art. As such, though, The Game provides a distinct and edifying view into Williams’s creative process. The Williams archive contains dozens of drawings from The Game, fortuitously saved by the Williams family.

The Game was similar in structure to the surrealist parlor game called the “Exquisite Corpse.” Also known by its French title, Cadavre Exquis, this game was invented in Paris around 1925 by André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Prévert, and Yves Tanguy. To play, each participant sketches one segment of what is usually a trifold drawing, with the paper folded such that the other drawings are hidden.88 Small lines indicate where the next person should connect their drawing. Unfolding the drawing reveals an “exquisite corpse,” at once beautiful and ghastly, made up of three connected but essentially random sketches. The name was born early on when the surrealists, led by their founder, the French poet Breton, first played it with words, resulting in the nonsense sentence, “Le cadavre / exquis / boira / le vin / nouveau,” or “The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine.” The illustrated version of the Exquisite Corpse emblematized the surrealist spirit, privileging chance and whimsy and tapping into the unconscious. Individual agency was subsumed into the group dynamic.

The likely forbearer to the Exquisite Corpse is a nineteenth century paper-and-pencil game called “Consequences,” which involves multiple players who each contribute one sentence to a story detailing something that happened and what its consequences were. Breton commented that the Exquisite Corpse was like a pictorial adaptation of Consequences, noting, “Surely nothing was easier than to transpose this method to drawing, by using the same system of folding and concealing.”89 Although we have no evidence that Williams engaged in these kinds of pencil games during his tour of duty, the parlor games and much of the historical documentation of them originated in Europe, just like the modern art that so intrigued him.

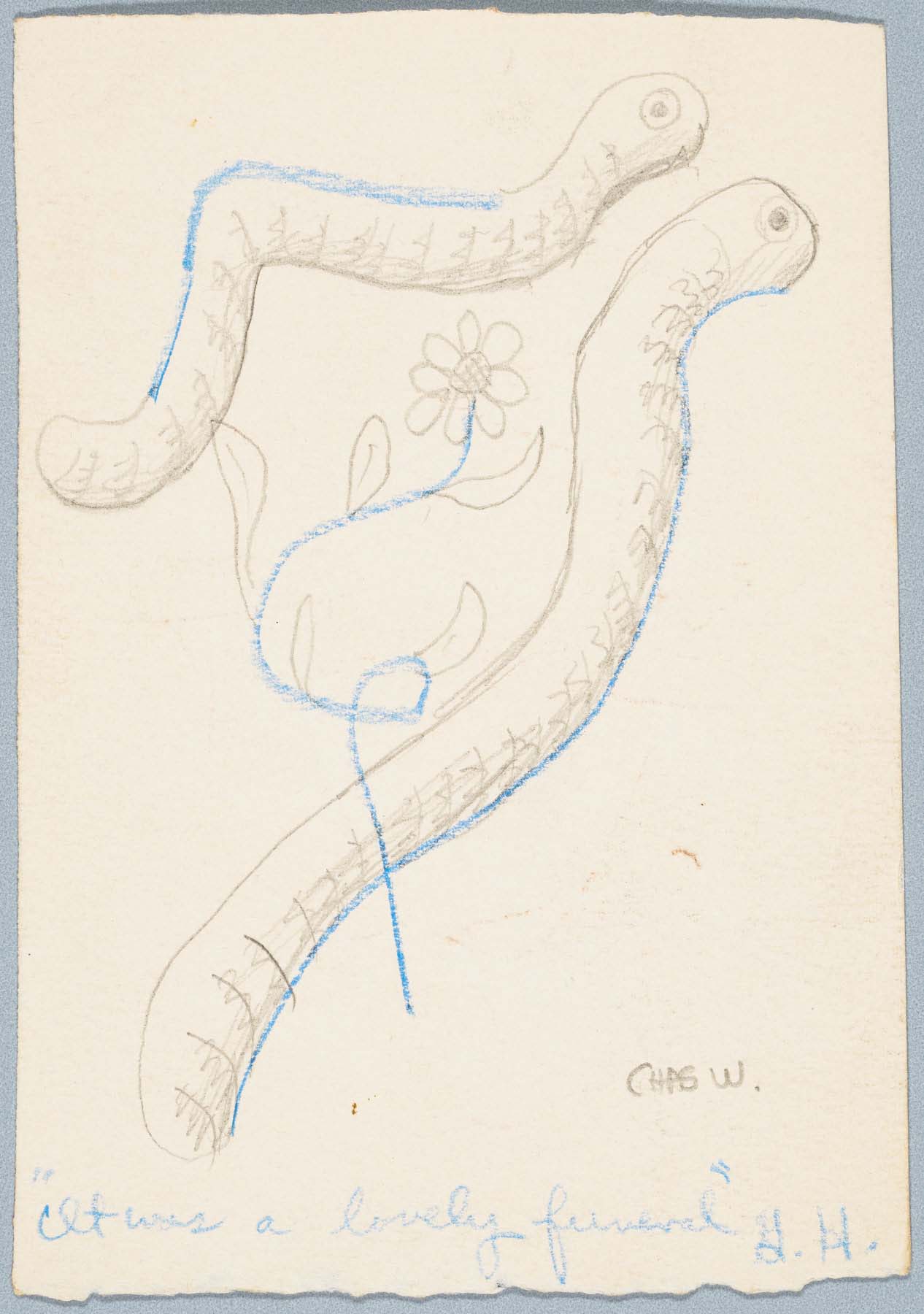

The twenty-seven examples of The Game exhibited in The Art of the Scene attest to the broad variety of studio visitors who played it. In one turn of The Game, a guest named Georgie Harris contributed three simple blue lines and the title “It was a lovely funeral” (fig. 3.17). With a colored pencil, Williams transformed Harris’s lines into two wide-eyed worms and a flower. The drawing is basic; the humor stems from the absurdity of talking worms remarking on a funeral, using the incongruous adjective “lovely.” The finished drawing and caption are unremarkable, perhaps generating a quick smile when Williams and Harris showed it to their friends. Williams used shading to give the worms dimension and added worm-like “segment” lines. In fact, It was a lovely funeral bears a striking resemblance to Williams’s “Ell” series of the 1960s, one of his last. For the Ell sculptures, Williams pieced together prefabricated industrial metal known as Ells to create curved columns, as in his 1965 piece Components (fig. 3.18), or donut shapes like Small Blue Torus (1966). Then he painted them in brilliant metallic colors. The formal similarities between It was a lovely funeral and Components, with its blue and green overlapping Ells that look like vertical earthworms, are compelling, suggesting that while the artist was casually playing The Game, his creative pistons were firing and he envisioned future three-dimensional objects.90 Looking at Components with the drawing in mind, one can see the spirit of anthropomorphized worms in the twisted blue and green metal tubes.

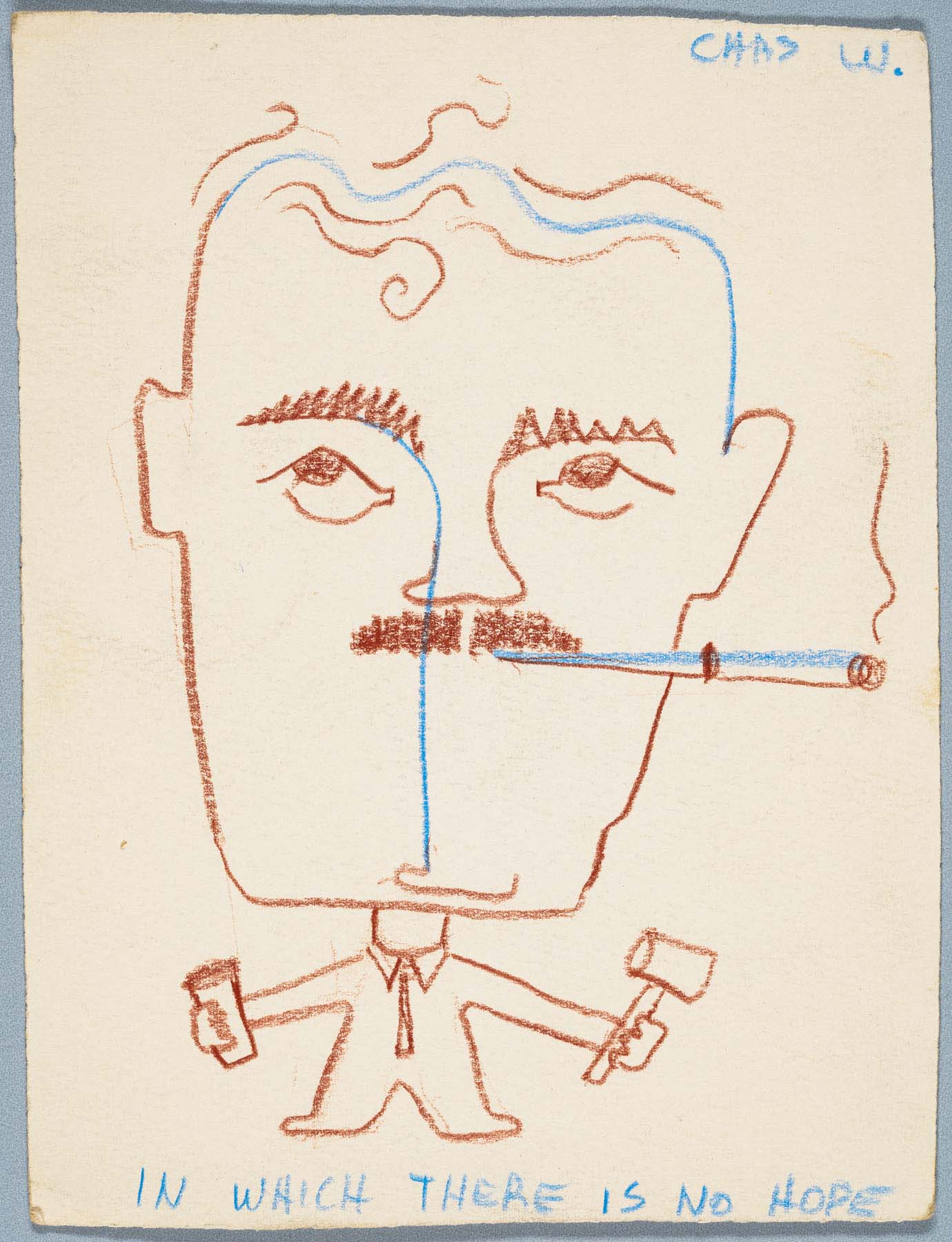

Williams himself is the subject as well as one of the makers in The Game drawing titled In Which There Is No Hope (fig. 3.19). He first drew three blue lines and signed his name “CHAS W.” Next, with brown pencil or crayon, his unidentified partner (most likely a good friend) made the lines into a portrait of Williams himself with a giant head, wavy hair, thick eyebrows, moustache, and a lit cigarette in its holder. The sculptor wears a necktie; one hand holds a mallet, the other seems to hold a glass of beer. Whoever made the drawing surely reveled in poking fun at his host, the very person who generated the work’s title, completely oblivious that in a few strokes he would be the unwitting star of that round of The Game. No doubt the evening’s guests erupted in laughter when they were shown the finished drawing.

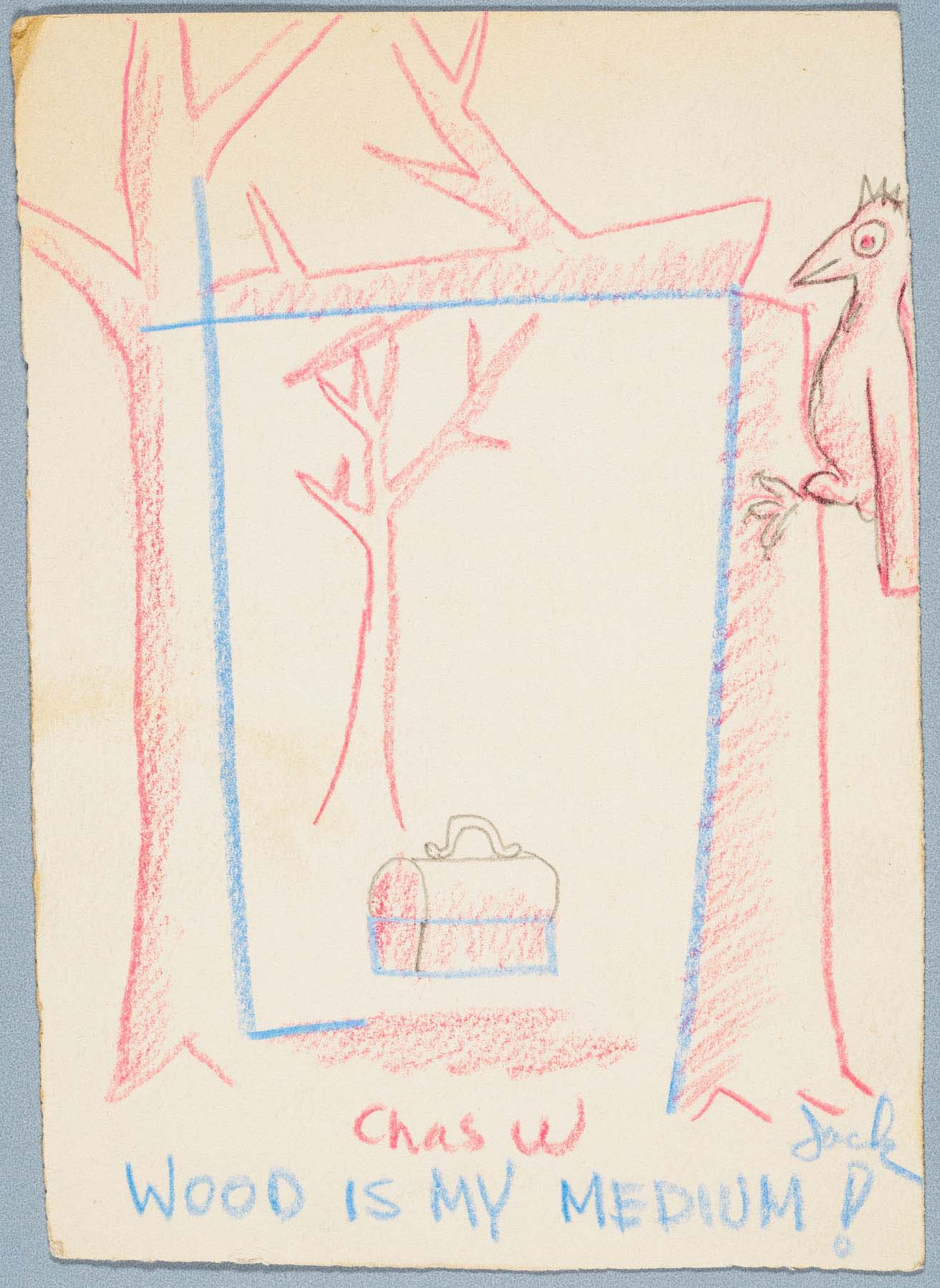

In a collaboration with Jack Boynton, Wood Is My Medium! (fig. 3.20), Williams seems again to be the subject, although more obliquely. In blue pencil, Boynton provided the title and lines that almost form a square surrounding a smaller rectangle. Williams used red pencil to transform it into a landscape in which a woodpecker just chopped down a tree with its beak. A lunchbox—presumably belonging to the working woodpecker-lumberjack—rests at the center of the scene.

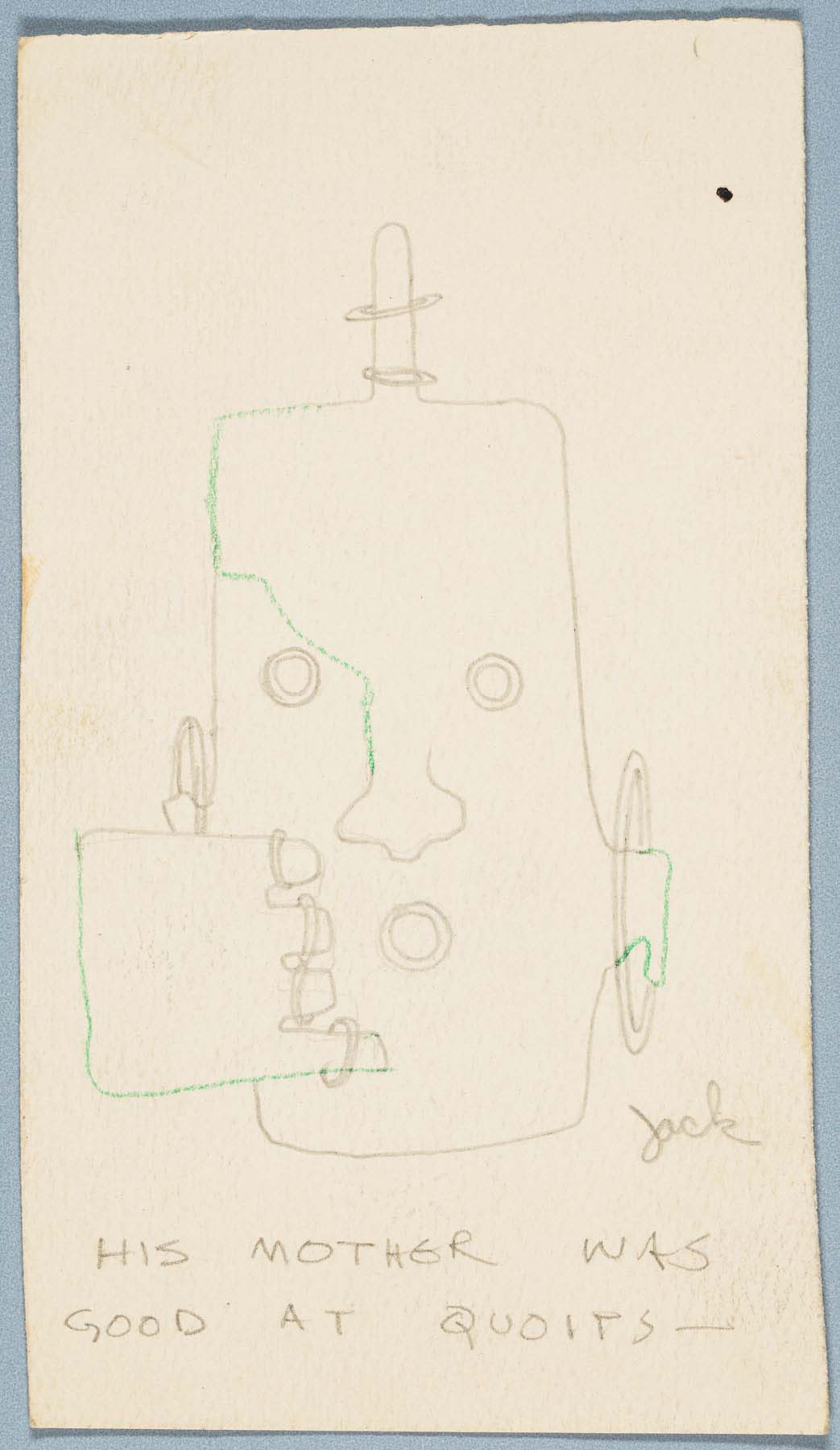

Another drawing, His Mother Was Good at Quoits (fig. 3.21), depicts a game within The Game.91 Quoits, a traditional ring-toss game, was first recorded in the United Kingdom in the early nineteenth century, though it is probably much older. The rings can be made of wood, rubber, or metal, cast onto spikes or pins, and can be played outdoors or indoors. A tabletop version was once popular in pubs. His Mother Was Good at Quoits originated with three green lines (from an unidentified contributor) that Boynton transformed into a person with rings encircling his ears, fingers, and a dowel-shape (like a ring holder) that juts out from of his head. The figure’s eyes and mouth are also represented as rings. Although primarily a painter, in this sketch Boynton toyed with three-dimensional views, drawing the quoit rings from various angles. The mischievous and absurd image is surrealist at its core, a double entendre on the obsessions of motherhood (a mother so extreme about her game that she raised a quoit-headed son) and the Freudian implications of a game of pegs and rings. Like all The Game drawings, it serves as a metaphor for the creative process itself—or the multiple creative processes—that happened in Charlie’s studio. Along with their mutual love of art, Boynton and Williams shared an appreciation for the ludicrous. Much like the Exquisite Corpse, the collaborative rules of The Game encouraged chance connections that brought the players closer to the unconscious.

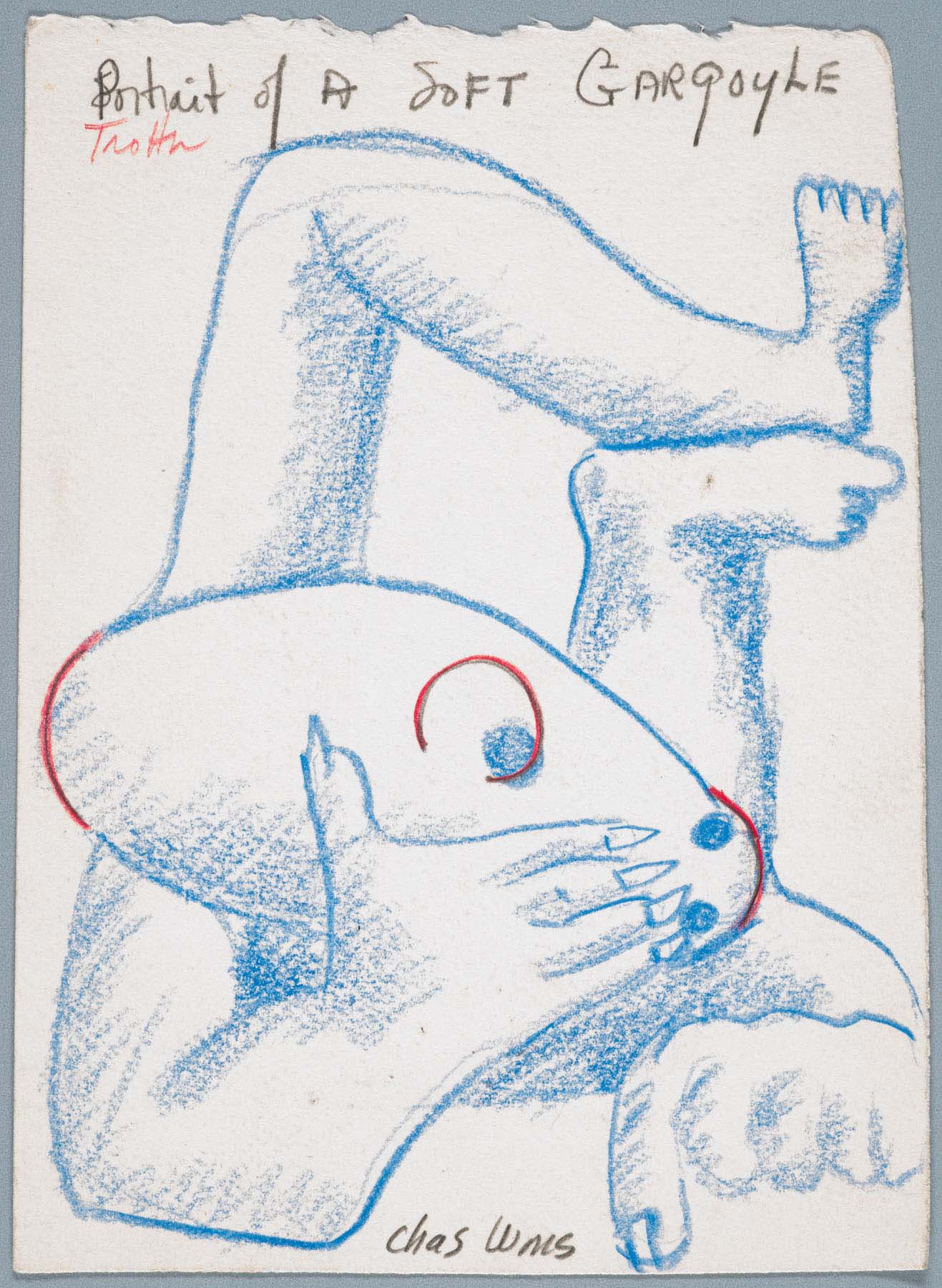

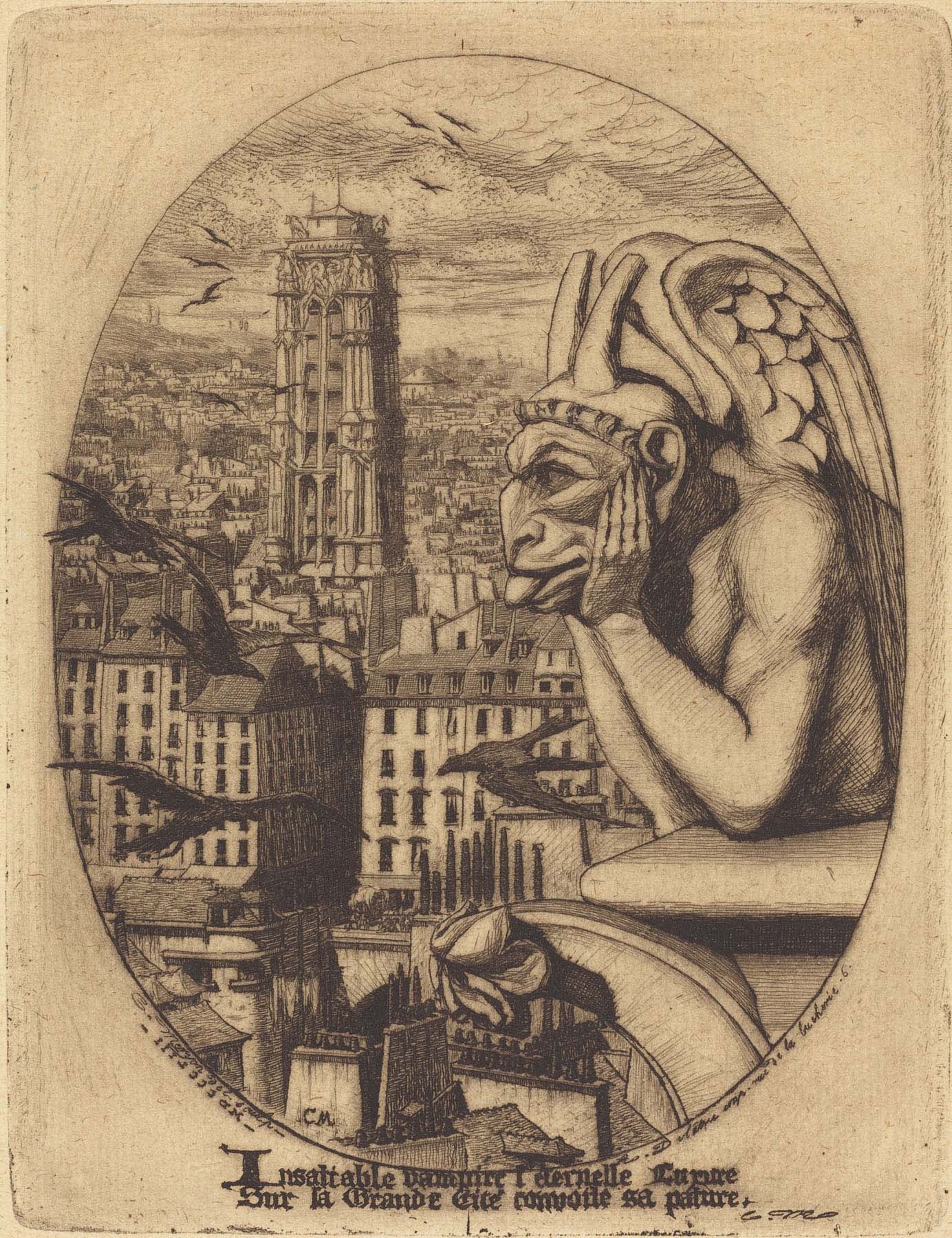

Williams was the draftsman in Portrait of a Soft Gargoyle (fig. 3.22), originated by McKie Trotter, who provided three abstract red lines and likely the title. The figure nearly fills the page, with legs and arms bent to create a rectilinear form, as the gargoyle’s right hand holds up its head. Like in the worms drawing, the humor here derives from irony: gargoyles are made of stone and intended to look frightening, but Williams’s version looks bored, even silly. The gesture of a gargoyle resting its head on its own clawed hand is like that of the beloved so-called “Stryge” chimera on the north tower of Notre-Dame de Paris, who holds its head in both its hands (fig. 3.23). Its contemplative pose, as if gazing out at all of Paris, led artists and photographers to immortalize Stryge, or “the vampire.” The Game’s Portrait of a Soft Gargoyle has fingernail claws more akin to artist Charles Meryon’s 1853 etching of the Stryge chimera than to the actual stone figure at Notre Dame, suggesting Williams had familiarity with the print.

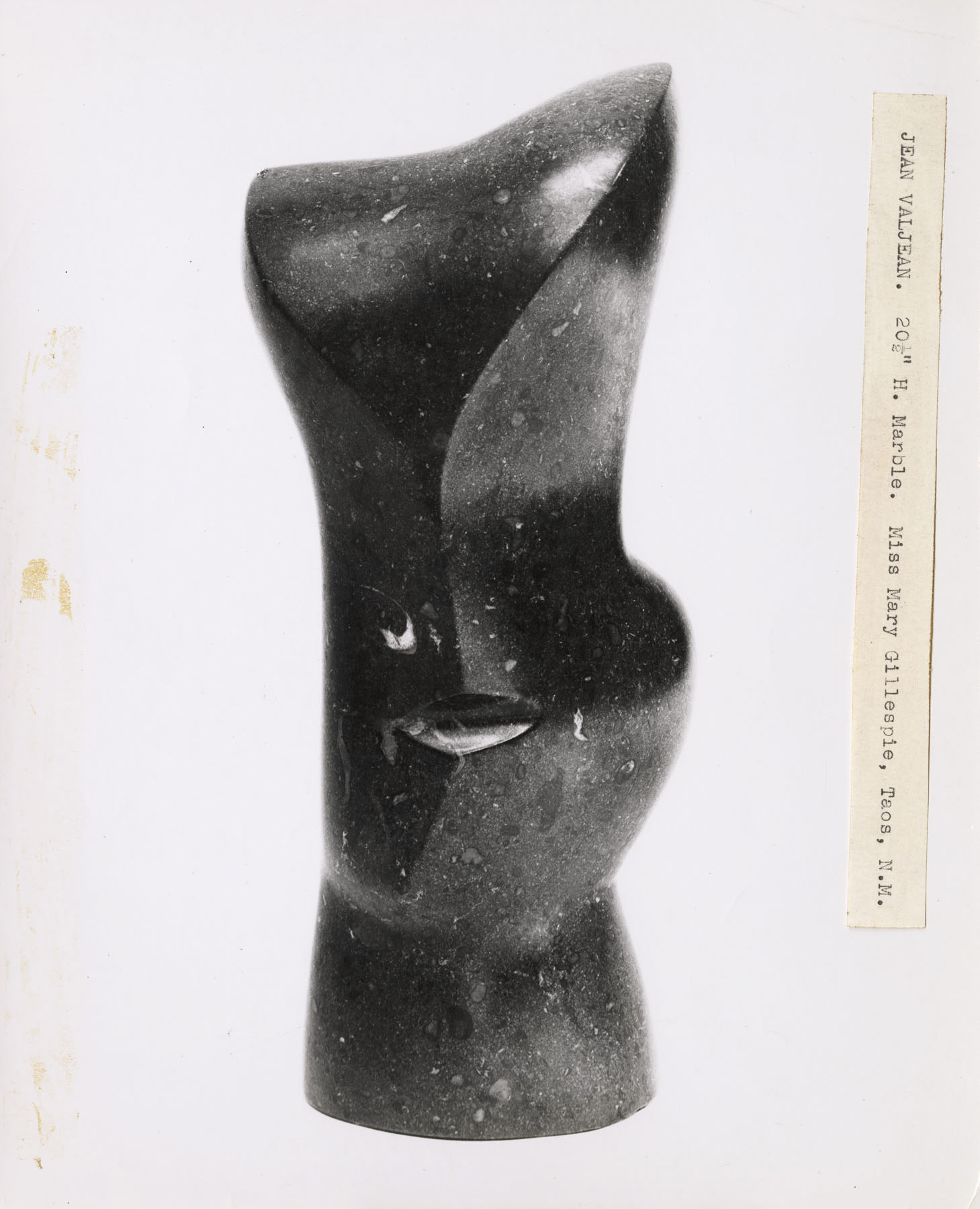

Williams was also acquainted with the stone chimera and with its origin story. His 1945–46 datebook entries document at least one visit to Notre-Dame de Paris on the Île de la Cité, and his curiosity likely would have led him up to the Tower with Chimeras. Notre-Dame was the setting for Victor Hugo’s classic 1831 Notre-Dame de Paris, known in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. Although it introduced the now-legendary hunchback, Quasimodo, the novel’s primary protagonist is the cathedral itself. Quasimodo considers Notre-Dame’s monsters and demons to be his friends and guardians. Hugo’s tale allegedly inspired French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc to add chimeras, including Stryge, to the cathedral during a major restoration project in the 1840s. Williams found inspiration in another Victor Hugo novel for his 1952 marble sculpture Jean Valjean (fig. 3.24), named for the criminal-turned-hero of Les Misérables (1862). Perhaps Williams had read the book, or he had seen the 1935 Academy Award-winning Hollywood movie of the same name that starred Fredric March and Charles Laughton.

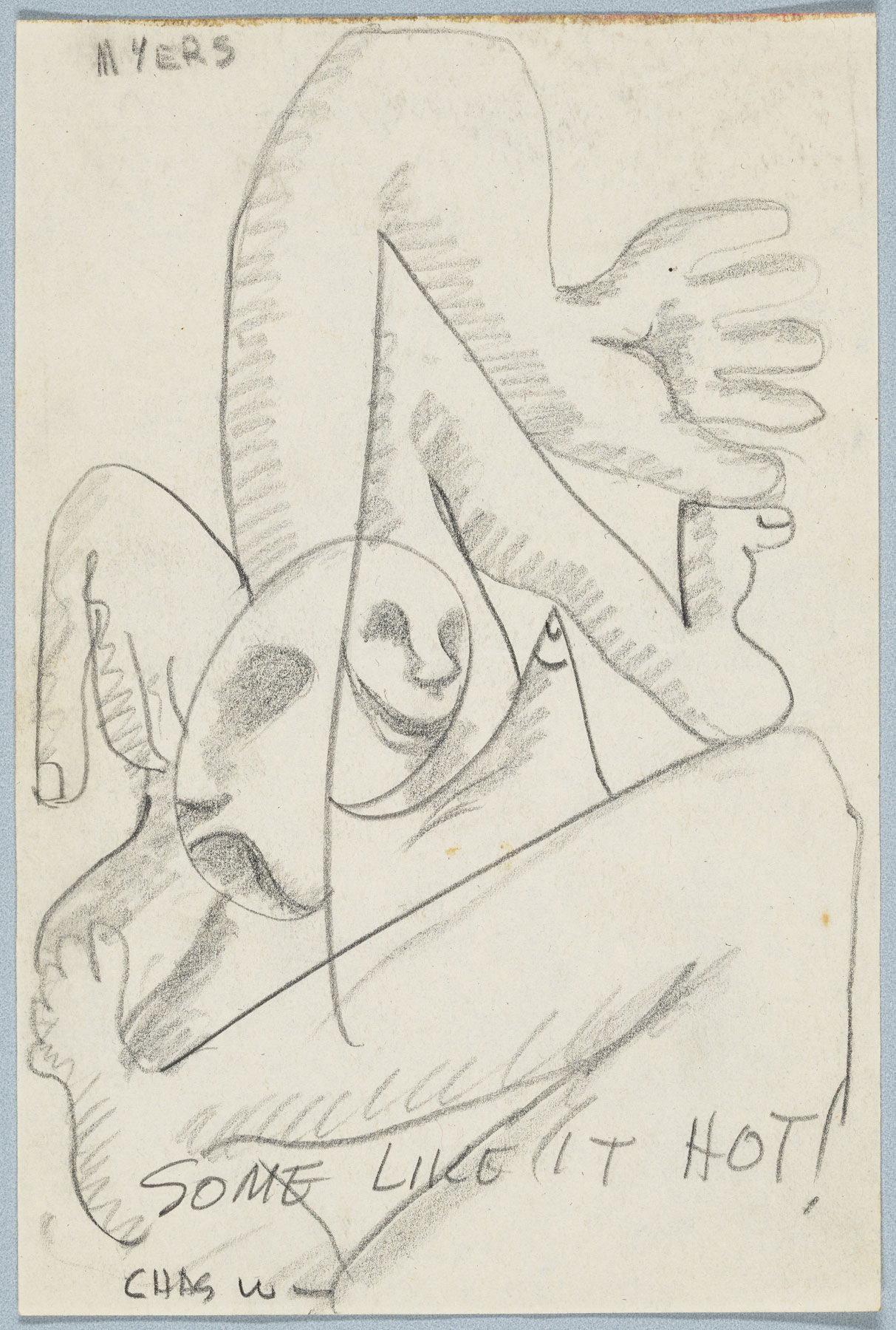

Hollywood almost definitely provided the inspiration for another turn of The Game. In the drawing Some Like It Hot! (fig. 3.25), the participants were someone named “Myers,” who provided the initial lines and title, and Williams, recognizable as the draftsman.92 The drawing’s title seems to have been lifted from the romantic comedy Some Like It Hot! starring Marilyn Monroe, directed by Billy Wilder, and the winner of six Academy Awards. The film came out in 1959, offering a terminus post quem for the drawing. Williams filled the page, much as he did in Portrait of a Soft Gargoyle, with a jumbled, entangled mix of two people. It is a fitting illustration of the movie, which revolves around two male musicians played by Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis who accidentally witness the mob’s 1929 Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago. To escape retribution, the characters disguise themselves as women and join an all-girl band. Monroe plays Sugar Cane, the band’s sultry lead singer and the object of both men’s affection. Williams renders a clever interpretation of the film: As in theatrical comedy and tragedy masks, one of his faces smiles, the other has a downturned mouth. The figures’ genders are not identifiable, yet there appears to be a breast jutting up. The Game drawing invokes the topsy turvy action of the film while also punning on the raunchy theme that sexually, some people like it “hot.”

The drawing also reflects Williams’s profound visual and tactile interest in women. In a 1948 letter, Lîlá made a highly percipient observation about Williams’s fascination with the female form, both in real life and plastic recreations. Of course, the two of them almost certainly visited multiple art exhibitions together, looking at painted and sculpted female figures, the latter of which also abound in public art throughout Europe. In her letter, Lîlá seems to have been eagerly awaiting a reply from Charlie to her previous missives. Probably motivated by worry, her jealousy comes through: “Keep away from women and go ahead with your art, you’ll get more satisfactions [sic] out of it.”93 In her entreaty for him to “keep away from women,” Lîlá, perhaps knowingly, set up a false dichotomy. For Williams, women and art were inextricably entwined.

Williams created more artworks based on the female form than any other subject. In the wide variety of media with which he engaged—wood, marble, cast bronze, hammered copper, welded rods, prints and drawings, to name a few—he obsessively revisited the physical, sensuous qualities of the female body. He explores the shape as a monumental abstract deity, as in the marble Earth Mother (pl. 13), and in the smooth walnut breasts, belly, and hips of the nearly life-size, quasi-geometric Torso #2 (pl. 3). Throughout his investigations, we find Williams playing with his aesthetic media, as in the hammered copper Odalisque (pl. 9) commissioned by Ridglea Country Club. In one clever example, Seated Figure (pl. 6), he harnesses line by creating a drawing in three-dimensions using bent and welded metal rod. The sculpture toys with negative space, incorporating it as an integral component of the female body. As a final flourish, Williams channeled his ribald humor into the sculpture by adding curly metal pubic hair.

Charles T. Williams went to Europe for work, but it was the history, the art scene, the sense of novelty and playfulness, the bars, and the people that left the most lasting mark. It was a time in his life when work and play were forced to be separate things, when combining the two meant not much more than drawing or taking photographs as he walked to work. As he gained critical skills during his time in the Army Corps, Williams committed himself to his artistic passions, romance, and meeting influential people from all over Europe and America, finding that his love for these things did not have to be mutually exclusive. The crass, crude, and erotic were elevated to high art, and high art was brought to bars and pubs and romance. Each fed into the other, with his romantic exploits providing inspiration for his art and his art attracting the eye of women like Louise, Lîlà, and Anita. In modernism, Williams found an artistic style as bold and eager as he was, a movement that sought to reimagine what it meant to be an artist or even a person, a movement that, like Williams, sought to blur the lines between work and play.

Perhaps he was simply born with that special single-mindedness that artists need to really thrive, or perhaps it was slowly nurtured and awakened during his time in Paris. Regardless, he returned home with an expanded mind and sense of the world, and through unfortunate circumstances found himself in Texas, hardly the cradle of culture that he had grown accustomed to in Europe. Ever the opportunist, however, he ingratiated himself with what was a relatively young and burgeoning modern art scene; his wit, humor, and good nature made him a locus of ideas, people, and artistic exchange. Through his time in Fort Worth, we see how his love of play became ever more entwined with his art, through both the playful nature of his work and the parlor games that filled so many evenings. It is as though he took everything that he adored about Paris and set about making it flourish in Fort Worth.

One object in particular symbolizes Williams’s longing for a European artistic ambiance: In 1952, he crafted a beautiful L-shaped wooden bar, simplified and modern, but nonetheless reminiscent of Harry’s Bar and all those other places where he spent his evenings in Paris. The bar itself stood for many years in Williams’s own Fort Worth studio, a resting place for the drinks and elbows of so many artists and intellectuals, friends and lovers, coworkers and playmates. Perhaps it is fitting that Williams saw the bar, a place of drinking and merrymaking, as perfectly compatible with and in fact vital to his working space. Indeed, for Williams, art always imitated play, and play always imitated art.

NOTES

-

Unless otherwise noted, sources for biographical details are documented in this volume’s chronology. ↩︎

-

Karl Williams, conversation with the author, April 6, 2022. ↩︎

-

Between February 4 and June 24, 1951, Williams took a leave of absence from the corps to focus on his education. ↩︎

-

Scott Grant Barker, “Karl Williams Oral History Transcript” (unpublished manuscript), 2021, 4, Amon Carter Museum of American Art Oral History Archives. The full quotation is poignant: “There was not a moment that that drive ever left him, and I think that probably contributed to some of his health issues and probably contributed to his early death.” ↩︎

-

Douglas MacAgy, one i at a time (exhibition catalogue) (Dallas: Pollock Galleries, Meadows School of the Arts, Southern Methodist University, 1971), 9. ↩︎

-

Ryan Moore, “The Bob Crozier Collection: Aerial Reconnaissance in World War II,” Library of Congress, February 9, 2017, https://blogs.loc.gov. ↩︎

-

“Application for Federal Employment,” June 7, 1948, in Army Corps of Engineers Records [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. Charles Truett Williams Papers, Amon Carter Museum of American Art (hereinafter, “ACMAA Williams Papers”). ↩︎

-

Diana R. Block, “Introduction,” in Charles T. Williams, Retrospective with Friends (exhibition catalogue), ed. Diana R. Block (Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 1998), xi. ↩︎

-

Before Williams was drafted, LIFE magazine published an article titled “New French Art: Picasso Fostered It Under Nazis” (November 13, 1944, 72–76). In 1947, according to LIFE magazine, Picasso was “the most talked about man in Paris” and “More people try to get into his studio than into any other private place in Paris” (Charles Wertenbaker, “Portrait of the Artist,” LIFE, October 13, 1947, 97). ↩︎

-

The German government labeled many international artists “degenerate” and organized a major touring exhibition of over 600 objects of degenerate art (Entartete Kunst) in Munich in 1937, featuring mostly German works; over 2 million visitors attended. ↩︎

-

Williams’s Paris girlfriend, Lîlà Ménard, wrote in a 1949 letter that the Canadian Peter Sager (an artist they both seemed to know personally) “will do work in Picasso’s studio” (Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], September 13, 1949, in Correspondence - Lila [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers). ↩︎

-

Photos of Picasso in his studio during the war were published in both LIFE and Vogue in 1944. According to Alfred Barr Jr., director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York: “Since the liberation of Paris, Picasso has been very much in the news; and visits to his atelier have developed almost a standard pattern. Indeed Captain Philip W. Claflin, recently on leave in New York, reports that groups of G. I.’s are taken like tourists through Picasso’s studio every Thursday morning” (Alfred H. Barr, “Picasso 1940–1944: A Digest with Notes,” The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 12, no. 3 (January 1945): 2, 5). ↩︎

-

Germain Viatte, Aftermath France, 1945–1955: New Images of Man (London: Barbican Gallery, 1983), 27. ↩︎

-

Charles de Gaulle publicly insinuated that Antoine Saint-Exupéry was supporting Germany, which allegedly drove the author into a bout of depression. ↩︎

-

André Breton, co-author of the Surrealist Manifesto and the movement’s founder, took charge of admitting members and was known to “excommunicate” artists from official Surrealism. Countless writers and artists, however, were influenced by the movement’s style and how it privileged the unconscious mind and automatism. ↩︎

-

Viatte, Aftermath France, 13. Paris’s reigning position as the international art world capital would not last long after 1945. In the 1930s and 1940s, so many artists had emigrated to the United States and rubbed shoulders with American artists that New York City soon took over as the leader in the art world. ↩︎

-

Clément Thiery, “Summer 1945, American GIs at the Sorbonne,” France-Amérique, August 27, 2020, https://france-amerique.com. ↩︎

-

Viatte, Aftermath France, 27. ↩︎

-

Andrew Israel Ross, “Urban Desires: Practicing Pleasure in the ‘City of Light,’ 1848–1900” (Dissertation in History, The University of Michigan, 2011), 101–7. ↩︎

-

The “African mask” origin for the two figures in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon has never been definitively established, although they resemble ceremonial masks from the Fang people of Gabon. ↩︎

-

Christopher Green, Picasso: Architecture and Vertigo (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 51. ↩︎

-

The classic essay on the Museum of Modern Art’s embrace of “primitivism” is Thomas McEvilley, “Doctor Lawyer Indian Chief: ‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art at the Museum of Modern Art in 1984,” Artforum 23, no. 3 (November 1984): 54–61. ↩︎

-

Andrew Meldrum, “Stealing Beauty,” Guardian, March 15, 2006, https://www.theguardian.com. ↩︎

-

The painting led to the development of Cubism and much twentieth-century modern art and appeared in numerous publications. In its October 13, 1947, issue, LIFE magazine reported somewhat dismissively on Picasso: “[with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon] Picasso launched into his ‘Negro’ period. He transferred to his own canvases the fearsome distortions and grotesque colors of Africa’s witch doctors, painting sharp, elongated noses, staring button eyes and pointed bellies. Around Picasso swarmed cultists who made him the high priest of modern art, collected fetishes made with bits of African hair and teeth. To induce the proper primitive mood some even took ether or hashish as the master himself once did” (Charles Wertenbaker, “Picasso,” 94). ↩︎

-

Karl Williams, email to the author, May 2, 2022. ↩︎

-

Thomas Motley, “The Sculptural Works of Charles T. Williams,” in Block, Charles T. Williams, Retrospective with Friends, 7. ↩︎

-

Block, “Introduction,” xi. The names of artists Williams saw in Paris are repeated by many, yet aside from considerable visual evidence, we don’t have anything definitive documented from the artist himself. The Trocadéro/Musée de l’Homme was one of the few museums open during the Occupation; its director was actively involved in the Resistance. ↩︎

-

Williams’s African-style mask is visually similar to the style of the Dan people from the Ivory Coast or Liberia. ↩︎

-

Katie Robinson Edwards, Midcentury Modern Art in Texas (Austin: University of Texas, 2014), 225. For a discussion of the racism of “primitivism” in Texas, see pp. 214–28. Also see S. Janelle Montgomery, “An Advocate for Art: Charles T. Williams in Fort Worth” in this volume. ↩︎

-

Charles T. Williams, “Agenda,” 1946, January 26, March 18 and 24, uncatalogued notebook in ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Williams, February and March. There is no mention of visiting the former Trocadéro/Musée de l’Homme. ↩︎

-

Williams, February 20. ↩︎

-

Charles [T. Williams] to [Louise Williams], November 16, 1945, in Correspondence - General [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Barker, “Karl Williams Oral History,” 2. ↩︎

-

Kelly Fearing discussed this with the author. One of the Fort Worth Circle artists traced everyone’s feet so he could give them ballet slippers for Christmas. ↩︎

-

Charles T. Williams, [Photographs of Paris], 1945–46, in Photographs - World War II [1]-[4] folders, ACMAA Williams Papers; Williams, “Agenda,” January 23. ↩︎

-

The full text read “Un Document sensational et [illegible]: Le Carnet de Notes d’Hermann Goering” (“A Sensational and [illegible] Document: The Notebook of Hermann Goering”). Hermann Goering (also Göring) was the lead architect of the Nazis’ police state and was convicted as a war criminal at Nuremberg. ↩︎

-

One Army report estimated that eighty percent of single men and fifty percent of married men engaged in sexual relations during their stay in Europe during World War II. “Sex Overseas: ‘What Soldiers Do’ Complicates WWII History,” Radio (New York: WNYC, May 31, 2013), https://www.wnyc.org. ↩︎

-

“Sex Overseas.” ↩︎

-

Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], June 29, 1948, in Correspondence - Lila [2] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], March 21, 1949, in Correspondence - Lila [2] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], October 5, 1947, in Correspondence - Lila [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], February 7, 1948, in Correspondence - Lila [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Lîlá to Charles, June 29, 1948. ↩︎

-

Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], November 4, 1947, in Correspondence - Lila [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Williams never moved to Germany or Austria. It is possible the process was stalled due to an outstanding debt he owed to Hardin-Simmons University. Louise Williams died in August 1947; by October that year Williams was living at his parents’ house on El Campo in Fort Worth. Charles T. Williams to Business Office, Hardin-Simmons University, October 26, 1948, in Army Corps of Engineers Records [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers; “Application for Federal Employment.” ↩︎

-

By October 13, 1947, Lîlà was aware that Louise Williams had died. ↩︎

-

Lîlá’s divorce announcement doubled as a 1966 New Year’s greeting; Williams died of a heart attack in March of that year. The card reads “Avec ses meilleurs voeux pour une heureuse année 1966 Giséle Lippens vous annonce son divorce d’avec André Ménard” (“With her best wishes for a happy new year 1966, Giséle Lippens announces her divorce from André Ménard”) (“Giséle Lippens Divorce Announcement,” January 14, 1966, in Correspondence - Lila [2] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers). ↩︎

-

Simon Difford, “Harry’s Bar,” Difford’s Guide - for Discerning Drinkers, December 17, 2015, https://www.diffordsguide.com; David Chazan, “A Century of Harry’s Bar in Paris,” BBC News, November 25, 2011, https://www.bbc.com. ↩︎

-

“In 1923, Harry MacElhone, its former barman, bought the bar and added his name to it. He would be responsible for making it into a legendary Parisian landmark.” In 1960, Ian Fleming forever linked James Bond to Harry’s New York Bar in the short story, A View to a Kill (“Harry’s New York Bar,” Wikipedia, July 2, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org; “Harry’s New York Bar Paris, France,” Atlas Obscura, n.d., https://www.atlasobscura.com). ↩︎

-

Williams, “Agenda,” May 11. ↩︎

-

Charles to Louise, November 16, 1945. Williams documents another meeting with Rivington on March 25, 1946. Two quizzical references in Williams’s 1946 agenda mention meeting a “Chas. W. Hauke / Hanke / Hawke.” It is possible this was a nickname for César Mange de Hauke, an art dealer who was in Paris during the war, looting artworks during the Nazi era and selling them to established galleries such as Knoedler (Williams, “Agenda,” January 3). ↩︎

-

Katie Robinson Edwards, “Gene Owens Oral History Transcript” (unpublished manuscript), 2008, 75–76. According to Karl Williams: “I was told by CTW’s studio assistant and frequent driver, Leon Walters, that CTW visited with Miller while he was on a trip to California. Somewhere around here there’s a battered Obelisk Press copy of Tropic of Cancer also a number of other Miller books out of the studio bookcase” (Karl Williams, email to author, May 2, 2022). ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Owens Oral History,” 77; Karl Williams, email and conversation with the author, April 30, 2022. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Owens Oral History,” 76. ↩︎

-

“I.B.F. Trap No. 1” (Harry’s New York Bar, ca 1946), in Photographs - World War II [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Owens Oral History,” 72. ↩︎

-

Williams, “Agenda,” May 16. ↩︎

-

A.L. Hetherington, Chinese Ceramic Glazes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1937); R. Horace Jenkins, Practical Pottery for Craftsmen and Students (Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing, 1941). ↩︎

-

Williams, “Agenda.” Regarding the Kiln Dealer - July 5; “get library books on Chinese Ceramics and Practical Pottery” - July 16; “glazes” - August 31; “buttons, kiln, glazes, blueprint of plaster mixture” - September 2; “books and plaster” - September 17; “[Announcements],” The American Ceramic Society Bulletin 25, no. 5 (May 1946): 51; Bruce J. O’Connor, “Ceramic and Structural Clays, and Shales, of Whitfield County, Georgia” (Information Circular 73, Atlanta, 1988), 50, https://epd.georgia.gov. ↩︎

-

Henri Matisse, Odalisque couchée aux magnolias, 1923, oil on canvas, 1923. ↩︎

-

George Fortenberry, “A Friendship,” in Block, Charles T. Williams, Retrospective with Friends, 12. ↩︎

-

Fortenberry, 13. ↩︎

-

After the war, the GI bill swelled the enrollment of colleges and universities, leading to an increase in art professors who had steady salaries and could therefore work in any style they chose. In the decade after the war, this phenomenon began to be associated ideologically with American freedom and was used as a political tool internationally. See Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom and the Cold War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983). ↩︎

-

Charles T. Williams, “The Design and Execution of a Fountain Sculpture” (MFA Thesis, Texas Christian University, 1955). ↩︎

-

Joe [Williams] to Charles [T. Williams], September 8, 1947, in Correspondence - General [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

“Record or Request for Approval of Promotion and/or Reassignment,” June 28, 1943, in Army Corps of Engineers Records [3] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Scott Grant Barker, email to Amon Carter staff, July 1, 2022. Also see Kendall Curlee, “Fort Worth School,” Texas State Historical Association, January 30, 2022, www.tshaonline.org. ↩︎

-

Jane Myers, “Progressive Rebels and True Believers: How the Fort Worth Circle Made Art New,” in Intimate Modernism: Fort Worth Circle Artists in the 1940s (exhibition catalogue), ed. Jane Myers (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 2008), 21. For the studio and Williams’s connection to the Fort Worth Circle, see S. Janelle Montgomery’s essay. ↩︎

-

Barker, email. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, Midcentury Modern Art in Texas, 329. ↩︎

-

Boynton calls it “night school”; his future wife, Ann Williams (no relation to Charles) was also in TCU night school. ↩︎

-

Karl Williams has pointed out that Boynton was very much like Williams in that he was completely dedicated to art and to being an artist, all the time. That may have contributed to why Boynton and Charlie hit it off immediately (Karl Williams, conversation with the author, April 6, 2022). ↩︎

-

Katie Robinson Edwards, “Jack Boynton Oral History Transcript" (unpublished manuscript), 2007, 6. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, 4. ↩︎

-

Eleanor Kempner Freed, “Art: Requiem for a Sculptor,” Houston Post, April 10, 1966, clipping in microfilm reel 1803, Charles T. Williams Papers, 1949–1966, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (hereinafter, “AAA Williams Papers”). ↩︎

-

Kempner Freed. ↩︎

-

Lîlá to Charles, November 4, 1947. ↩︎

-

Matt Szal, “Sculpting the New Circle” (unpublished manuscript), n.d., 4, essay in Williams, Charles folder, Amon Carter Museum of American Art Artist Files. ↩︎

-

Gene had spent a summer at the University of Texas Austin learning mold-making from Charles Umlauf. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Owens Oral History,” 85. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, Midcentury Modern Art in Texas, 207. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, 207. James Johnson Sweeney, the Director of The Museum of Modern Art, likely visited Charlie’s studio ca. 1953 or 1954; Sweeney visited Boynton, Erickson, and Trotter’s Fort Worth studios at the suggestion of Dan Defenbacher (Robinson Edwards, “Boynton Oral History,” 17). ↩︎

-

Charles and Anita, Karl’s third grade teacher, married in August 1951. Karl was in fourth grade and it was Charles’s last year at the El Campo studio. Presumably, getting remarried spurred Williams to find a new home. ↩︎

-

“Douglas G. MacAgy Dies at 60; Hirshhorn Exhibitions Curator” (obituary), New York Times, September 7, 1973, 38; Robinson Edwards, Midcentury Modern Art in Texas, 228–31. ↩︎

-

MacAgy, one i at a time, 9. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Owens Oral History,” 73. ↩︎

-

All these artists were involved in the Dada and Surrealist movements, which had been underway since World War I. Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. ↩︎

-

David Mitchell, “Write and Fold Games,” The Public Paperfolding History Project, n.d., http://www.origamiheaven.com. ↩︎

-

Because The Game drawings are undated, it’s difficult to discern which came first, the drawing, It was a lovely funeral, or the sculpture, Components. What is clear is that Williams was moving back and forth between two- and three-dimensions, and the drawing either forecasted or recalled a completed sculpture. ↩︎

-

His Mother Was Good at Quoits is signed “Jack,” which could be Jack Erickson and not Boynton. Based on the handwriting and the existence of other The Game drawings signed “JWE” (Jack Erickson), the Quoits draftsman seems to be Jack Boynton. In this case, Boynton may also have added the title. ↩︎

-

We were unable to identify who all The Game participants were, even with the generous assistance of Williams’s son, Karl. Only “Myers” last name is known as of this writing. ↩︎

-

Lîlá to Charles, June 29, 1948. Later in that sentence she explains, “and . . . so I may have a chance to keep you.” ↩︎

| words