Foreword

- Jonathan Frembling

It is always a joy when doing research to find connections between seemingly unrelated elements. This is often that “aha!” moment for historians. History is not limited to the stories of kings and nations; it also includes the small details that make moments a living thing. It is often these small, seemingly trivial details, especially as they build up, that create the richest stories.

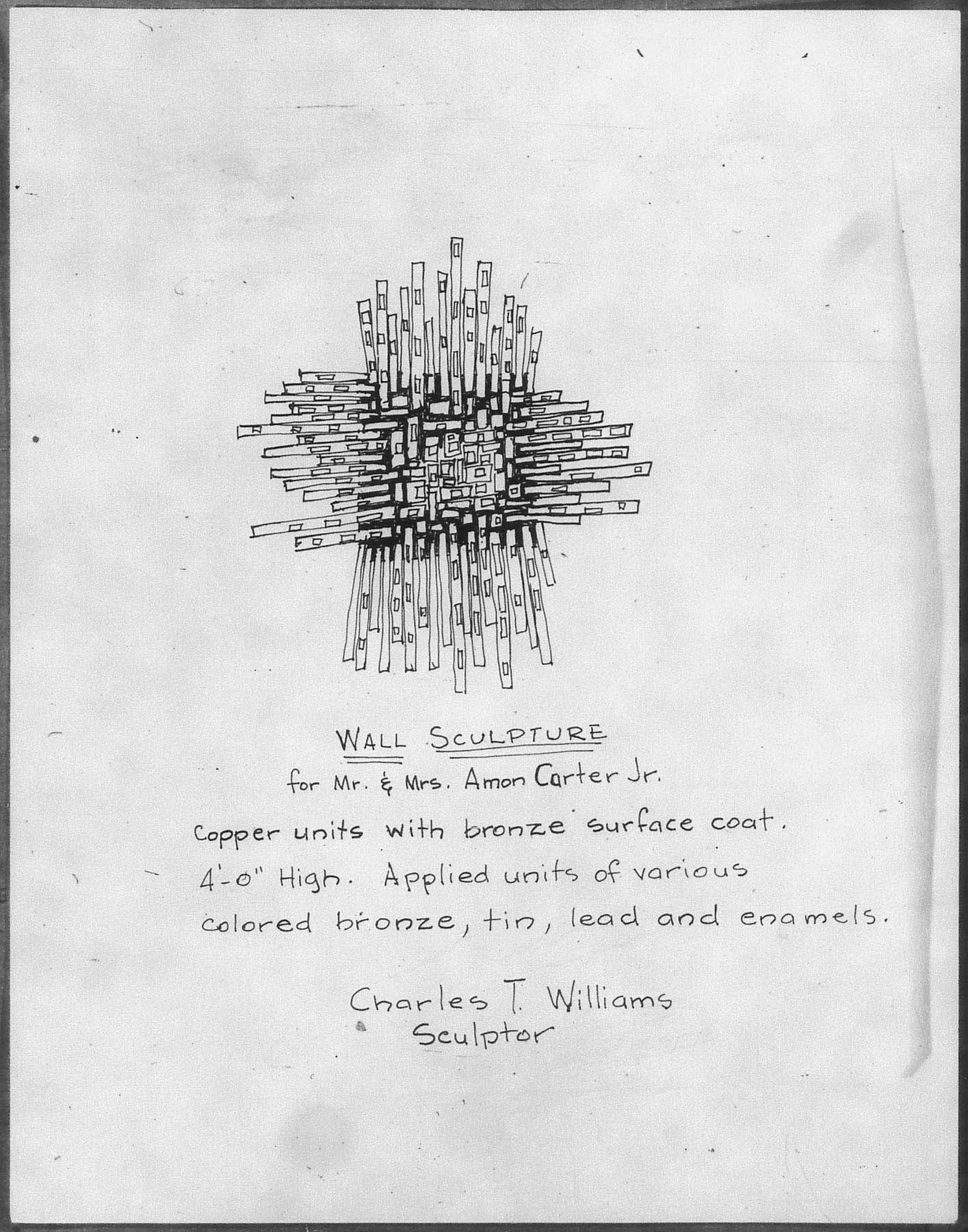

Take for example the Carter family, best known in Fort Worth for their role as civic boosters. Amon G. Carter Sr. became known in the national media as “Mr. Fort Worth” for his tireless promotion of the city and creation of its Cultural District. Similarly, his daughter Ruth Carter Stevenson became nationally known for her role in the arts, building the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in honor of her father and later serving as the president of the National Gallery of Art. Conversely, Amon Carter Jr., son and brother respectively, was best known as a businessman. Finding a link during this project between him and Charles Truett Williams—the subject of this publication—was a genuine delight that adds a further chapter to the Carters as arts patrons (fig. 1.1).

Since its founding in 1961, the Carter has become a leader in art scholarship through its rigorous research program, publications, and initiatives such as the Gentling Study Center, which was founded in 2019 to mine the art and archival riches of the Museum’s collection for the unknown, the unexpected, and the innovative. Charles T. Williams is an ideal case study for this initiative. He was an inventive artist, working at a pivotal moment in art history, and a man with a unique talent for drawing in other talented artists and enhancing their work. This publication is the result of scholars' delving into our archives to find this story outside the well-trod narrative of American art history.

This publication would not exist without two key figures: Shirley Reece-Hughes and Karl Williams. It began with Reece-Hughes, curator of paintings, sculpture, and works on paper at the Carter, and her decades-spanning engagement with the art and artists of Texas—such as the Fort Worth Circle and the Dallas Nine. Her publications and exhibitions laid the groundwork that led to Williams, and it was her introduction to Karl, son of the artist, in 2018 that initiated this project. Karl Williams has been a tireless promoter of his father’s legacy. An artist in his own right, widowed husband of a gifted sculptor, and studio assistant to his father from boyhood, he is immersed in the viscera of art making. It is his deep commitment and passion for the subject that led him to choose the Carter as the repository for his father’s work through the gift of the Williams Papers, which served as the wellspring for the new scholarship found in this publication.

This study tapped the singular knowledge of Katie Robinson Edwards, executive director and curator at the UMLAUF Sculpture Garden and Museum in Austin. A leader in the study of Texas art, Edwards’s previous publication on the subject is the standard against which this book will be measured. Her essay in this publication is amplified by that of S. Janelle Montgomery, Gentling Fellow at the Carter, whose trailblazing research led not only to a groundbreaking essay on the artist but to a comprehensive chronology of his life and of the art scene he moved in.

The refinement of this publication is the result of the often-unrecognized work of many hands. Will Gillham, editor and publisher at the Carter, shepherded the manuscript from inception to completion, ensuring wayward essayists, suspect prose, and artistic ambitions came together to make something worthy of the subject. Michelle Padilla, digital content strategist at the Museum, was instrumental in the identification of the platform and design of this publication. Selena Capraro, associate registrar, spent many hours pursuing the requisite permissions to make all the images and figures in the publication available, and Paul Leicht and Steve Watson, photographers at the Carter, captured images of Williams’s dispersed works and prepared the image files for the book. Without their collective work there would be no art in an art book. My sincere thanks to Scott Grant Barker, a ready font of expertise on the arts in Texas, who peer-reviewed the essays. Finally, I thank Greg Albers and Erin Cecele Dunigan at the Getty Research Institute, who provided support for the Getty’s Quire platform through which this publication is presented, and Stephanie Alger at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, who happily offered advice as someone who had gone before us in working with the platform.

This publication, then, is the study of a gifted artist that would not exist without the generous gift of his son and gifted circle of scholars and professionals. Each has brought, through their dedication and labor, something that is a credit to themselves and a service to the future. I extend my profound gratitude and respect to them all.

Jonathan Frembling

Gentling Curator and Head of Archives