An Advocate for Art: Charles T. Williams in Fort Worth

- S. Janelle Montgomery

At the end of World War II, as Europe rebuilt and the bulk of the Western art world completed its shift from Paris to New York, the art scene in the city of Fort Worth began a transition of its own. In 1945 a gallery run by the Fort Worth Art Association (FWAA) provided almost all of the city’s art exhibitions and programs (fig. 4.1). Public schools offered art instruction, which the FWAA supplemented with gallery lectures and classes, at least for the White children. Those seeking advanced education looked to the north and east, to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) or the Art Institute of Chicago. A group of artists now known as the Fort Worth Circle dominated local and regional exhibitions. Most of them had roots in the city, and many had trained on the East Coast and traveled extensively in Europe. During the war, they put their skills to work as designers and model makers in the defense industry. Their art reflected their encounters in Europe, bringing modernism to a town of 200,000 where many of their patrons claimed descent from early Anglo settlers.

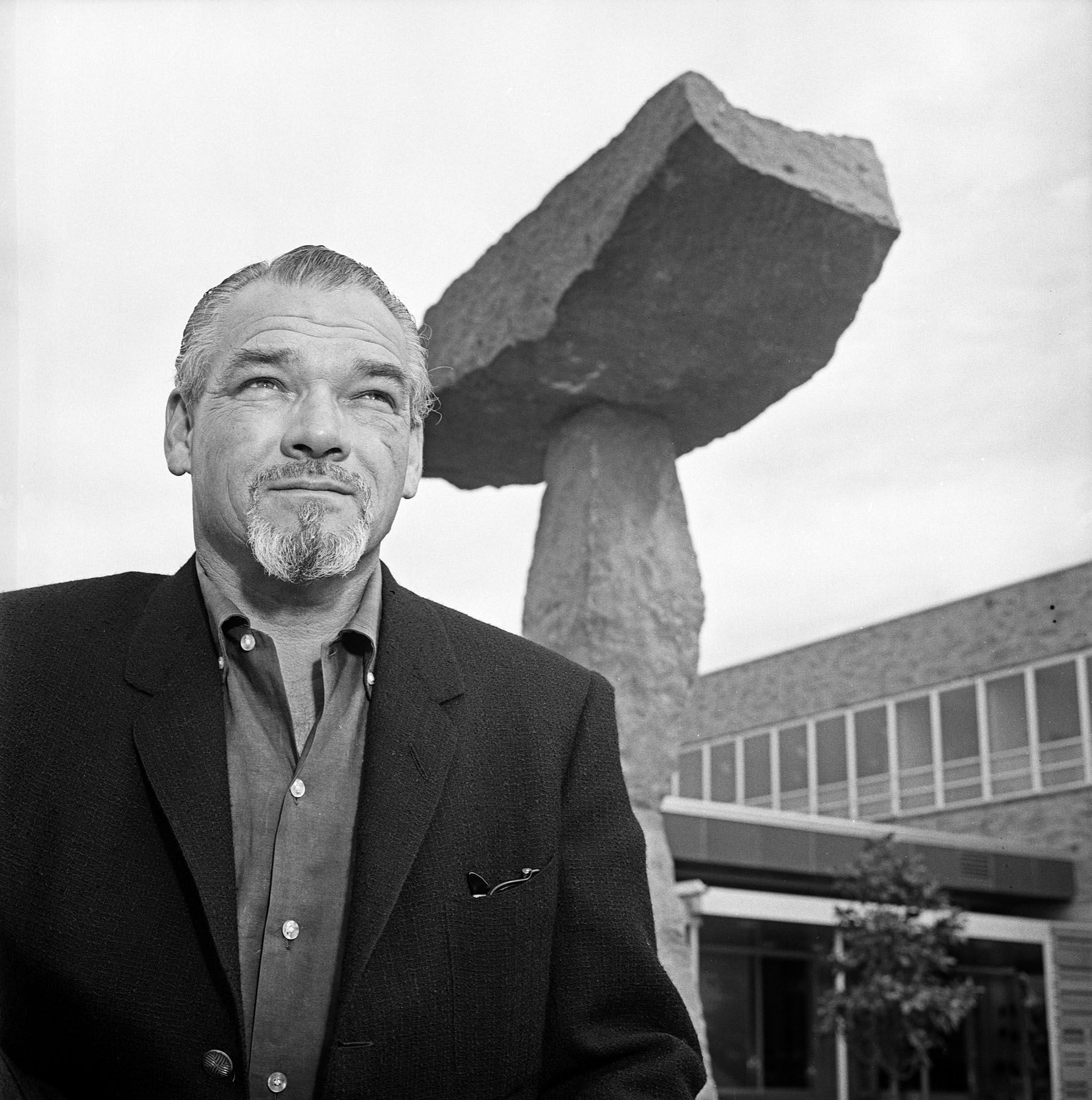

Charles Truett Williams (1918–1966) came to Fort Worth in October 1947. A photograph of him taken around 1921, when he was about three years old, looks like millions of other childhood pictures, except Williams’s hands seem too big even for his chubby toddler’s body (fig. 4.2). As he grew, he made his first forays into art with drawings and prints. Following high school, he worked as a stonemason, later joining the Army Corps of Engineers, which employed him as a draftsman for many years. Shortly before turning thirty, Williams took up sculpture. He initially worked in ceramic and, after settling in Fort Worth, progressed to wood, stone, and finally metal, making pieces at once monumental and intricate. He rapidly mastered materials and techniques and quickly won recognition. He shared his knowledge freely, and his studio became a gathering place for anyone interested in art. Williams advocated for art in Fort Worth, cultivating collaborations with his fellow artists and museum and gallery professionals to improve standards of art production and exhibition. By the time he died, a brief two decades later, “Cowtown” boasted two full-fledged art museums, both housed in modernist architectural gems, with a third on the way.

A Place for Art

Although it was far from clear for Williams in 1947, the move to Fort Worth secured his future as an artist. Born into a farming family in Weatherford in 1918, Williams graduated from Mineral Wells High School and went to work for his father, who had by then become a respected stonemason. Two years later, Williams enrolled at Weatherford Junior College. In 1939, he matriculated at Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, studying physics, math, and art. There he met Louise Beaver, a journalism student from Dallas who had been born in 1920 in Wichita, Kansas. By 1940, her junior and Charles’s sophomore year, the two of them were inseparable. She was associate editor of the newspaper and a feature editor on the yearbook; he worked as staff artist for both. They both belonged to the school’s Art League. The “Campus Couples” page in the yearbook calls them Torchy and Mr. Torchy.1 They married in February 1941 (fig. 4.3). At some point between 1930 and 1940, Louise’s family moved to Atlanta. The newlyweds joined them there, probably in mid-1941. Williams took a job as a civilian draftsman with the Army Corps of Engineers, studied life drawing at the High Museum of Art, and took evening classes in engineering drawing at Georgia Tech. In November, Louise gave birth to their son, Karl Boyd Williams.

In March 1944 the army drafted Charles and sent him to basic training at Fort Belvoir, Virginia.2 He was dispatched to Europe in early 1945. While stationed in Paris, Williams absorbed that city’s culture and took every opportunity to travel around the continent, as Katie Robinson Edwards discusses in her essay. Upon his discharge in June 1946, Williams returned to Atlanta and resumed his civilian duties for the Corps of Engineers. Almost immediately, he began to experiment with ceramics, as entries in his datebook and photographs in the archives attest (see fig. 3.13). Before the war, Williams’s artistic endeavors consisted of drawings and linocut prints. With ceramics he ventured into three dimensions, probably inspired by art he had seen in Europe.

One year after Charles returned to Atlanta, Louise contracted pneumonia and died. If that were not enough bad news, Charles’s employer told him his project had reached completion and “his services would no longer be needed.”3 Now a single parent with unemployment looming, Williams applied for and received a transfer to the corps’s Southwestern Division in Dallas. Proximity to his parents, who still lived in Mineral Wells, solved the problem of childcare. Charles and Karl completed the move west in mid-October, and the entire family soon relocated to Fort Worth, where Williams outfitted a studio in his parents’ garage.

Fort Worth in 1947 had a more vibrant art scene than many cities its size. It revolved around an institution, the FWAA, and a group of friends, the Fort Worth Circle. The association operated the city’s art museum, a single room built to function as exhibition space, sales outlet, and lecture hall on the second floor of the public library. The librarian, Jennie Scheuber, a vigorous champion of the visual arts as well as books, had been forced to retire in 1938 after directing the institution for nearly forty years.4 New leadership included a young banker, Sam Cantey III, and an established oilman, Robert Windfohr, each of whom served multiple terms as board president. The revitalized organization brought in more traveling exhibitions from the American Federation of the Arts, the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), the Smithsonian, New York galleries, and others. Some caused controversy, such as the 1942 Contemporary Figure Painting, which had more than a few nudes.5 In 1939, the FWAA inaugurated an exhibition inviting submissions from anyone in Fort Worth, which soon became known as the Local Artists Show, or often simply the Local.6 The show was an immediate and lasting success that continued annually for almost four decades.

By the mid-twentieth century, exhibitions like the Local provided the first step on the road to viability for artists in the western United States. A jury of one or more art critics, artists, curators, or teachers decided which submissions merited exhibiting. Sponsors, such as galleries, museum supporters, and local merchants, donated prize money; and the jurors or others, sometimes the general public, assigned awards. The exhibited works were typically also for sale. The exposure and press coverage might catch the eye of a gallerist, who might include an artist in a group show. If that went well, the gallerist might offer a solo show and perhaps a long-term arrangement. New York gallery representation marked the pinnacle of achievement. Museums might also mount a solo show for artists who regularly won recognition. Again, the works would be for sale, probably at higher prices since the artist now had a reputation. Making a living as an artist, however, required devoted patrons and a steady stream of commissions.

The quality of works at the Fort Worth Local in part reflected the community’s investment in art education. In 1924, the public schools for White children added art electives to the high school curriculum to complement compulsory art instruction in grades one through seven.7 Sallie Gillespie’s classes at Fort Worth Central High School (later Paschal High School) were particularly well-regarded; her students included Dickson Reeder and Bror Utter. Private instruction was also available, most notably from Christina MacLean and Sallie Blyth Mummert. Mummert taught Bill Bomar, Veronica Helfensteller, and Reeder. In 1932 Gillespie and two other PAFA alumnae, Blanche McVeigh and Evaline Sellors, established the Texas School of the Arts (later the Fort Worth School of Fine Arts); Helfensteller and Utter studied there. The friendships formed in these studios evolved into the Fort Worth Circle.8

Among the earliest of the Local’s prize winners were Reeder (1941 and 1943) and Utter (1942). After high school, Reeder studied at the Art Students League in New York; in Taxco, Mexico; and in Ireland, London, and Paris, where he met his future wife and fellow artist, Flora Blanc. The Reeders moved back to Fort Worth in 1940.9 They reconnected with Utter and with Bomar, who by then lived in New York but returned frequently to his hometown. Kelly Fearing came to Fort Worth in 1943 to work in the defense industry, where he met Reeder and was introduced to the group. Another native, Cynthia Brants, became involved following her graduation from Sarah Lawrence College in 1945. These artists and others shared ideas, criticism, and camaraderie at the Reeders’ Saturday evening salons and at weekly sessions in Helfensteller’s print studio. Donald Vogel, a newcomer from Chicago who settled in Dallas in 1942, later commented that he found acceptance of his work in Fort Worth that he did not in Dallas.10 During a period when a group known as the Dallas Nine defined cutting-edge art in Texas—their hard-edged regionalism contrasted sharply with prevailing impressionist styles—the Fort Worth Circle artists took inspiration from cubism, constructivism, surrealism, and other European modernist movements.

The Local helped the Fort Worth Circle artists not only by generating community interest in the arts but also by motivating artists to produce. Fearing remembered, “We waited for opening night with great anticipation, hoping to learn if our work had been accepted, and eager to know who had won awards. . . . Preparing and submitting works for that annual event served as a creative stimulus for all of us.”11 As a result of the Local’s popularity, the FWAA introduced annual solo shows dedicated to local artists. The first, in 1943, honored Blanche McVeigh. While many artists had day jobs teaching or working in the defense industry, and others had family wealth, the Local and the solo shows that grew out of it provided important sources of sales and income in a city with few commercial galleries.12 The events also attracted the interest of galleries in New York such as the Weyhe Gallery, which in 1944 hosted works by Blanc, Bomar, Helfensteller, Reeder, Utter, and Vogel in Six Texas Painters.

Cantey and Gillespie, who was secretary of the FWAA from 1945 until 1950, created the conditions for the local artists’ success, as Fearing described many years later:

[In Fort Worth] I associated with people who loved the arts, encouraged the artist, and collected their work. . . . [Cantey and] Gillespie organized the annual Local Artists Show and arranged for other art exhibitions that included the best of what was being shown in New York at the time. . . . It is difficult to put into words what a vital and important influence Sam and Sallie had on my development as an artist in those years.13

Gene Owens, who joined the Fort Worth art scene in the late 1950s, described Cantey’s passion for local art as one of “missionary zeal.”14 Cantey, in turn, tried to give all the credit to Gillespie, saying, “Gillespie as much as anyone before or since, was responsible for the resurgence of the appreciation of local art.”15

The enthusiasm for art generated by the FWAA and the Fort Worth Circle spread to the city’s institutions of higher learning. Texas Christian University (TCU) and Texas Wesleyan College (TWC, later Texas Wesleyan University) entered the war years with small visual art departments. TCU, from the time it moved to Fort Worth in 1910 until the 1939–40 academic year, had only one faculty member teaching painting and drawing with occasional sessions in sculpture, art education, art history, and related disciplines.16 TWC’s program took a step forward in 1919, when Scheuber convinced the school to hire PAFA alumnus Samuel P. Ziegler.17 The department consisted of one to two faculty and offered a limited curriculum into the 1940s. Ziegler left for TCU in 1925. From fall 1942 through spring 1945, Gillespie was the sole faculty member in the TWC art department; Fearing took her place until he left for the University of Texas in 1947.18

Scheuber and Gillespie were two of many women who made invaluable contributions to Fort Worth art, as artists, educators, and in museum leadership.19 Brants, Gillespie, Helfensteller, McVeigh, Sellors, a painter named Emily Guthrie Smith, and others participated in the Local and regional exhibitions as frequently as the men did, and they consistently won prizes. The Texas General Exhibition was the top event in the state, jointly organized by the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (DMFA, now the Dallas Museum of Art), the Witte Memorial Museum of San Antonio, and the Museum of Fine Arts of Houston (MFAH). In 1940, all five entries to the Texas General from Fort Worth were by women (the rest of the state-wide field was evenly split between men and women). Between 1945 and 1950, Gillespie effectively directed the FWAA gallery. In 1946, the twenty-two member Art Association board consisted of thirteen women, among them McVeigh as well as Bill Bomar’s and Cynthia Brants’s mothers, and nine men, including Cantey, Windfohr, and grocery- and grain-baron Kay Kimbell.20 On the other hand, the art world in Fort Worth, as in the rest of the United States, lacked ethnic diversity. Although some of the artists and occasional shows had roots in Latin America, no visitor of Black, Asian, Indigenous, or Hispanic heritage could attend the FWAA’s programs or exhibitions until the late 1950s or early 1960s.21 Exhibitions, FWAA membership, and artists’ salons belonged mostly to people of Northern European heritage.

With a popular exhibition line-up, the Association expanded programming. Fort Worth’s Junior League organized regular visits to the galleries for sixth graders, although probably only those from White schools. Sellors and Reeder, among others, taught classes. Open forums where the public could ask questions and high-profile lecturers, such as Guatemalan abstract painter Carlos Mérida in March 1943, drew considerable interest.22 As audiences grew, the space and operational constraints of the library gallery became increasingly frustrating. Supporters lobbied for a bond issue to build a free-standing museum. Although voters approved the initiative in 1945, little had changed by the time Williams arrived in Fort Worth two years later.

Spaces For Art

After the cosmopolitanism, energy, and personal freedom of post-war Paris and the trauma of losing his wife and job soon after resuming civilian life, Williams initially struggled to adjust to Fort Worth. Weekdays, he commuted three hours by bus to Dallas to work as a draftsman on water management projects.23 Evenings and weekends, he continued working with ceramics.24 An unsent letter to Lîlá, a Paris girlfriend, expresses his ennui:

To bring you up-to-date on my situation—can safely say that it’s just the same as it was six months ago. I am still in the same old ruts which I have been in for the past year. And what is the more unhappy thought [is that] I don’t see any changes to come in the near future.25

He cast about, applying for a government position abroad. He built marionettes and pitched them to television advertisers, possibly landing interviews, if not actual contracts, with Humble Oil and Pearl Beer (figs. 4.4 and 4.5).26 Experiments with sculpture held more promise. A November 1947 letter from Lîlá conveyed her excitement at learning of them: “Your hands—. . . . Sculpture is what your hands are made for, what your feelings and the strength of your [whole] body are made for.”27 He did not yet realize it, but Williams had found his calling.

In early 1948, Williams took advantage of the GI Bill and enrolled at TCU. The GI Bill brought students and funds that triggered a period of growth for the TCU art program. With Ziegler still at the head, in 1947–48 the department doubled its faculty to four, and the school introduced Bachelors and Masters of Fine Arts (BFA and MFA) degrees. This signaled a professionalization of art education that was also underway elsewhere. The expanded faculty included painter Jack W. Erickson, who arrived at TCU in fall 1947 with a BFA from the University of Illinois.28 Across town, TWC had a new art department head, McKie Trotter III, another painter, who held an MFA from the University of Georgia. Trotter left TWC for TCU in fall 1955. Larger enrollments merited better facilities, and TCU’s art department moved, along with music and dance, into a dedicated fine arts building in September 1949 (fig. 4.6).29

Shortly before, in May 1949, Fort Worth suffered a catastrophic flood. In addition to $12 million in property damage and at least eight people dead, the flood uprooted large black walnut trees in Forest Park.30 Williams salvaged the wood. Once it cured, he had a stock of quality material to work with, though he may still have lacked proficiency handling it. While TCU had no sculptor on the faculty when Williams enrolled, Leonard Logan III, who completed his MFA in sculpture and painting at the University of Oklahoma, joined in fall 1949.31 The next year, TCU expanded its art curriculum with classes in modeling, sculptural composition, plastic design, and sculpting in wood and stone; it also introduced a sculpture major.32

After school one evening, Williams invited his classmate Jack Boynton to the garage studio.33 Visits to “Charlie’s shop” grew into regular events, and Boynton introduced other TCU students to the gatherings, among them Bob Cunningham, Erv Harrison, and Boynton’s future wife, Ann Williams. New friends notwithstanding, Charles remained restless. In fall 1949, Lîlá drafted a budget for him, Karl, and Harrison to live in Paris.34 Williams aptly titled a redwood sculpture from this period Indecision (pl. 2). Heavy feet convey impossible-to-overcome inertia, while a giant index finger scratches its tiny head in a familiar gesture of rumination.

As Williams continued pursuing his BFA, sculptures he created from the Forest Park walnut trees gained him entrée to local, state, and regional exhibitions for the first time.35 Between 1949 and 1951, the Texas General and the Local accepted three: Torso [#1], Torso [#2] (pl. 3), and Fallen Angel. Over the next several years, Williams progressed to regional exhibitions, including the New Orleans Art Association show at the Isaac Delgado Museum, the Mid-America Annual in Kansas City, and the Annual Exhibition of Western Art in Denver. He frequently won awards, among them a purchase prize at the 1950 Mid-America Annual for Torso [#1].

Williams followed his successes in walnut with a move into stone. Throughout his life, he demonstrated a talent for acquiring sculpting skills with little formal guidance, but his early development closely followed Logan’s arrival at TCU. At the 1949–50 Texas General, for example, Williams submitted only sculptures of wood, while Logan showed a stone sculpture, Weasel Farm, and a marble one, Boar Head.36 The next year, Williams sent a limestone sculpture to the Local, Continuum (pl. 4). The parallels between the two men’s exhibition histories suggest Logan provided mentorship as well as technical knowledge. As Williams progressed, however, he worked out his own way forward, conducting experiments and advancing by trial and error to master processes for which, he said, he had no prototype.37

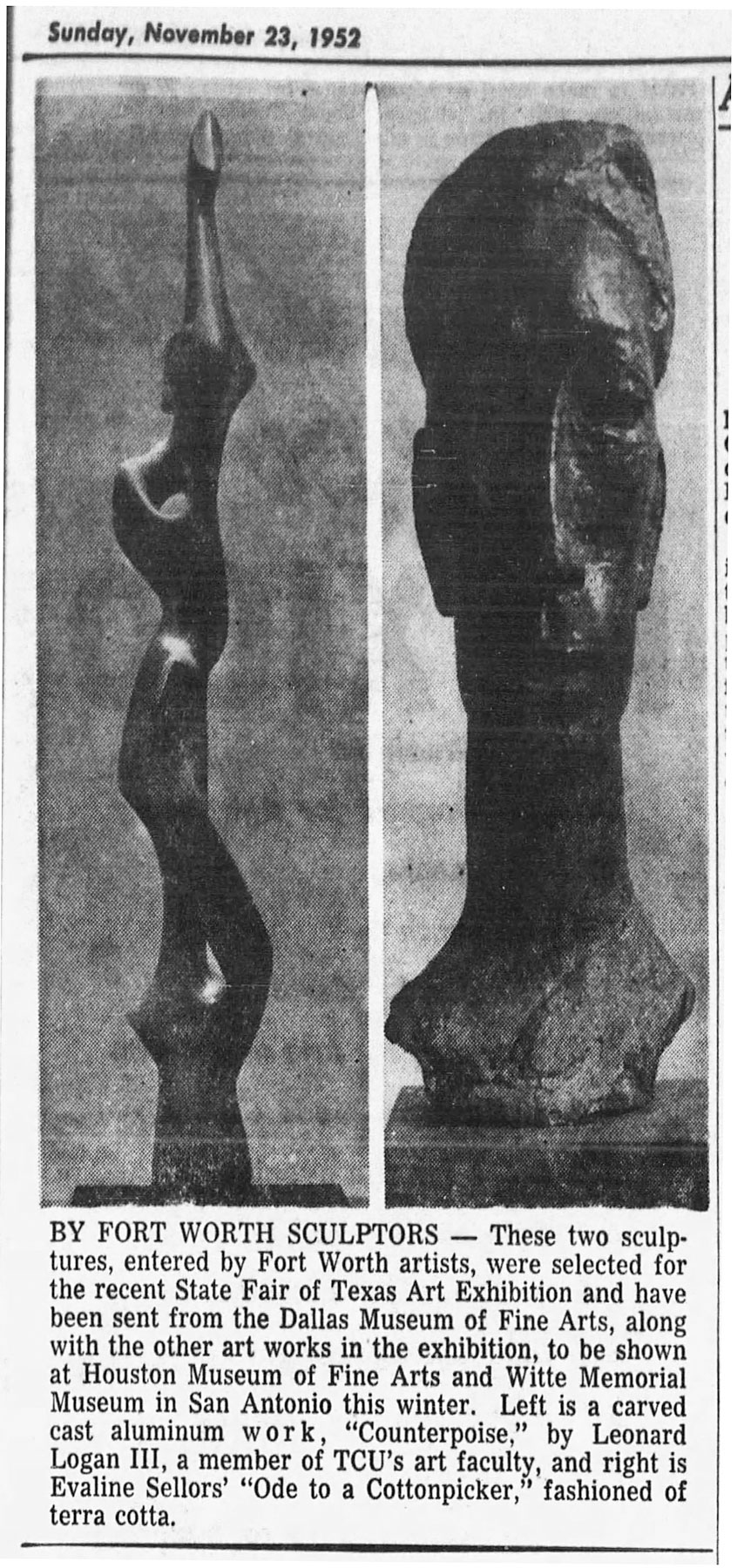

Evaline Sellors also regularly appeared on the same exhibition circuit as Logan and Williams (fig. 4.7). A native of Fort Worth, she trained in sculpture at PAFA and in Europe and taught at the FWAA, the Craft Guild of Dallas, and elsewhere.38 For several years, she and Williams took turns claiming first place at the Local. They provided mutual assistance, as well. Karl Williams remembers frequent errands between the two sculptors’ studios to drop off and collect tools and other necessities.39

In the 1951 Local, Continuum placed first, taking the Bertram Newhouse award for sculpture. Newhouse began sponsoring awards in various categories in 1947. His relationship with the FWAA dated to at least 1935, when the then Ehrich-Newhouse Gallery loaned an exhibition of old master paintings. Kay and Velma Kimbell made their first significant art purchase, The Artist’s Children, by Sir William Beechey, from the show. Newhouse oversaw the growth of the Kimbells’ collection for nearly three decades. Also in 1935, Amon G. Carter Sr. laid the foundation for his collection, acquiring Frederic Remington’s His First Lesson from Newhouse.

The FWAA enabled Kimbell and Carter, as well as others, to indulge their passions for art. At the same time, both families provided leadership and other support for the institution. Works from the Kimbells often appeared on the gallery’s walls; and Kay and Velma served on the Art Association board for many years. Carter also loaned works, and although he never held a board seat, his ex-wife, Nenetta Burton Carter, and their daughter, Ruth Carter Johnson (later Stevenson) did.40

In 1950, Gillespie left the FWAA and moved to Taos. Still seeking a space independent of the library, the association created the role of director and hired Dan Defenbacher from the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis to run the gallery, raise funds, and supervise the design and construction of a new building. Defenbacher arrived in June 1951. Almost immediately, he launched plans for an ambitious show of forty works by new artists, one of the most complex organized by the association to date.41 According to the catalogue, Texas Wildcat presented “a selective nationwide survey” of paintings by “established artists who had not yet attained a nationwide market.” It ran in Fort Worth from November 1 to December 31, 1951, then traveled to the DMFA and the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMOMA). In spite of the name, only two Texas artists made the cut: Brants and Clara McDonald Williamson, who had taken up painting in her sixties and produced stylized genre scenes and landscapes. For the San Francisco showing, however, Defenbacher added paintings by Bomar, Boynton, Erickson, Reeder, Trotter, Utter, and others.42 Texas Wildcat raised the profile of Fort Worth on the West Coast and burnished Defenbacher’s reputation, as well.

At home, the director focused on increasing memberships and public interest. He moderated a Saturday afternoon show on WBAP-TV called Your Art Center of the Air, for which Brants and the Reeders acted as consultants.43 Defenbacher also established an “artist’s subsidiary” membership group at the FWAA, which had a seat on the board and a voice in exhibitions and programming. To belong, an artist needed to have participated in a “necessary” number of “acceptable” juried shows. Its first president was Utter, followed by Trotter, then Williams. Members included Jack and Ann Boynton, Brants, Erickson, Logan, McVeigh, Dickson Reeder, and Sellors.44 Meeting minutes in the Williams archive show the group volunteering to organize fundraisers and offer demonstrations; planning a competition for murals and sculpture for the new building; recommending alternative formats, potential jurors, and a simplified award structure for the Local; noting that the gallery would benefit from better art reporting; encouraging the elimination of purchase prizes on the principle that a juror cannot know what makes sense for the permanent collection; and voting down a proposal for an un-juried show for local residents. Most ideas went unheeded, but the members of the artist’s subsidiary energetically supported the FWAA and adamantly argued for high standards for its exhibitions.45 Although Defenbacher may have organized the group, its enthusiasm and the tenor of its advice suggest Williams was actively working behind the scenes.

In fact, not long after arriving in Fort Worth, Defenbacher became part of Williams’s circle of art friends and colleagues. The group had grown as Williams settled into life in Fort Worth. In early 1951, Williams took a leave of absence from the corps to focus on his studies. He graduated with his BFA from TCU a year later. In August 1951, he remarried and gained a stepson. He and Anita McConnell, a teacher, met when Karl was her student. The four of them moved to an old farm southeast of the city. The studio and “Charlie’s shop” moved as well, and Anita proved an able and popular co-host. Regular guests included the now-married Boyntons, Cunningham, Erickson and his wife Jane, and Harrison. Trotter, still teaching at TWC, and his wife Sandra joined. As the Fort Worth Circle dispersed—Fearing took a job at the University of Texas in Austin and Helfensteller moved to New Mexico in the late 1940s—the Reeders, Sellors, and Utter frequented the Williams’s soirees, as did David Brownlow, a self-taught painter who was making a name for himself in the area. Betty McLean (later Blake), who opened Dallas’s first gallery devoted to contemporary art in 1951, made appearances as well. She hired Vogel as gallery manager and, within the year, they organized solo shows for Utter, Fearing, and Bomar. With Trotter tending bar, the group shared strategies, ideas, and diversions like “The Game” that Katie Robinson Edwards describes in her essay.46

As in the Fort Worth Circle, the artists in Williams’s orbit worked in a variety of styles and mediums, and several had experienced European modernism firsthand. They supported each other outside of social events. Williams loaned the studio to Trotter for life-drawing classes since nude models were prohibited on TWC’s campus; Trotter’s student Gene Owens met Williams through these sessions.47 The artists’ connections led Williams to Taos, where he discovered volcanic rock that he used in several sculptures (fig. 4.8).48 Boynton, Erickson, Trotter, and Williams showed together at numerous exhibitions and galleries, such as Lon Hellums’s gallery in April 1950 and Three Painters and a Sculptor at the FWAA in September 1952. Around this time, Williams began welding, assembling steel rods and plates into compositions that echoed some of Utter’s works in watercolor and oil (pls. 7 and 8).

When Guggenheim Museum curator James Johnson Sweeney scouted North Texas for an upcoming show, he consulted McLean. Defenbacher convinced Sweeney to consider a trio of artists from his side of town. Since Defenbacher had no loyalties to the Fort Worth Circle generation of Bomar, Reeder, and Utter, he happily promoted the artists coming out of TCU. In 1954, Boynton, Erickson, and Trotter represented Texas in the Guggenheim Museum’s Younger American Painters exhibition, sharing space with artists like Richard Diebenkorn, Philip Guston, and Jackson Pollock.49

Defenbacher’s most lasting contribution, however, was to complete the fundraising and organizing needed to build a home for the FWAA. The new facility would house a growing permanent collection and host exhibitions and programs, including films, theater, and musical performances. Ruth Carter Stevenson recalled meeting in 1951 to decide on an architect with her then-husband, lawyer J. Lee Johnson III; Sam and Betsy Cantey; and Bob Windfohr and his wife Anne, who was a ranching and oil heir. Unhappy with the city’s recommendation, the historic revivalist Wiley Clarkson, they instead selected Bauhaus-trained Herbert Bayer.50 It is hard to imagine such a choice would have been possible without the embrace of modernism by the Fort Worth Circle and their successors. The building opened on October 8, 1954, with an updated designation: the Fort Worth Art Center (FWAC) (figs. 4.9 and 4.10). Defenbacher, however, did not stay to direct the center; in May he had taken the job of president at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland. Henry Caldwell, formerly of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, assumed the top post at the FWAA the following April.

Judging from correspondence in the archive, Williams and others bemoaned Defenbacher’s departure. “The artists really feel your absence around here,” Williams wrote, “those which are left, that is. The Artist Group is still hanging on in spite of a movement to disband.”51 An earlier letter from Defenbacher indicates that he may have provided a boost to sculpture in particular, “Sculpture out here is at about the same level as it is everywhere. It needs promotion and we are working on it.”52 Sculptors face challenges that painters do not encounter. Painters can easily enter contests and exhibitions since canvases photograph relatively well and ship readily. A wall suffices for display. With sculptures, on the other hand, even photos from multiple angles fail to capture the entire viewing experience or their materiality. They can be heavy and difficult to transport, requiring bulky crates and special handling. Display often requires a pedestal and ample floor space.

Cantey remarked on the paucity of sculptors in Fort Worth on the occasion of a 1963 show at Neiman Marcus in the Square, noting, “Sculptors are still rare in Fort Worth but those we have are good and we have more than we used to have.”53 At the 1956 Texas General, juror Francis Henry Taylor humiliated the area’s sculptors in his comments: “The strength of the Exhibition lies in the paintings. The sculpture was not of the same high order and for this reason no sculpture was considered . . . for a cash award. . . . Except for the sculpture, the exhibition is one which ranks highly.”54 Dallas sculptor Octavio Medellín’s wood Joan of Arc, Gene Owens’s bronze Dog Barking at Moon, Sellors’s wood Saltamontes, and Williams’s steel Vertical Figures were among the sculptures Taylor found inadequate. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram reacted, “Is sculpture, long art’s stepchild in Texas, being kicked back to the scullery again after a brief fling as Cinderella?”55 Some considered withdrawing their works from the exhibition.56

Fortunately for Williams, by this time he had steady patrons in oilman Ted Weiner and his wife Lucile. They probably met through the FWAA.57 The Weiners, with Defenbacher’s help, built the first International Style house in the region, designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes, a student of Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer (fig. 4.11).58 With the completion of the house and its six-and-a-half acre garden in 1954, the Weiners started collecting modern sculpture in earnest. Along with works by Jean Arp, Harry Bertoia, Alexander Calder, Henri Laurens, Jacques Lipchitz, Henry Moore, Alicia Penalba, and Pablo Picasso, the Weiners acquired a number of works by Williams, including commissions for a large fountain for the garden and a fountain and sculptures for Ted’s offices at the Texas Crude Oil Company (fig. 4.12).59

Williams’s association with the Weiners encompassed building pedestals for their collection and repairing damaged works.60 It also led to other projects, such as three sculptures for the Ridglea Country Club: Odalisque for the cocktail bar (pl. 9), a fountain for the entryway (fig. 4.13), and a golfing figure for the men’s grill. The Weiner fountain and the country club commissions show the artist working on a much larger scale and mastering still more materials and techniques, such as hammered bronze and copper.61 The fountains required an appreciation for plumbing and armatures sufficient to sustain the weight of metal and water. Williams took inspiration from Asian calligraphy for the Weiner fountain; he detailed the design process and technical challenges in his MFA thesis (pl. 11).62

In August 1955, Williams received his MFA from TCU in absentia. He had suffered a heart attack several weeks earlier and was still recovering. At this point, he realized he had to make a choice. He could no longer continue holding down a full-time job and pursuing the creative life all night. With his recent commissions, he felt he could make it as an artist. He resigned from his job at the corps in September and devoted himself to sculpture.

A Case for Art

In October 1955, Williams addressed the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects, arguing that sculpture humanizes architecture and should not be neglected in building design. He considered two installations of Bertoia’s work outstanding examples of the practice, one at the Manufacturers Trust Company building by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and the other at the General Motors Technical Center designed by Eero Saarinen & Associates (fig. 4.14).63 Either Williams made a compelling presentation or had a receptive audience. He earned steady commissions for functional yet ornamental building components into the 1960s, from door pushes for All Saints Hospital (fig. 4.15) to light fixtures for the American Bank of Commerce in Odessa to a stair railing for Tarrant County Savings and Loan.64 The city of Dallas put Williams on the short list for a monument at Love Field Airport, but he did not make the finals (nor did Logan or Medellín).65 Charles Umlauf, a sculptor and professor at the University of Texas, ultimately won the commission.66

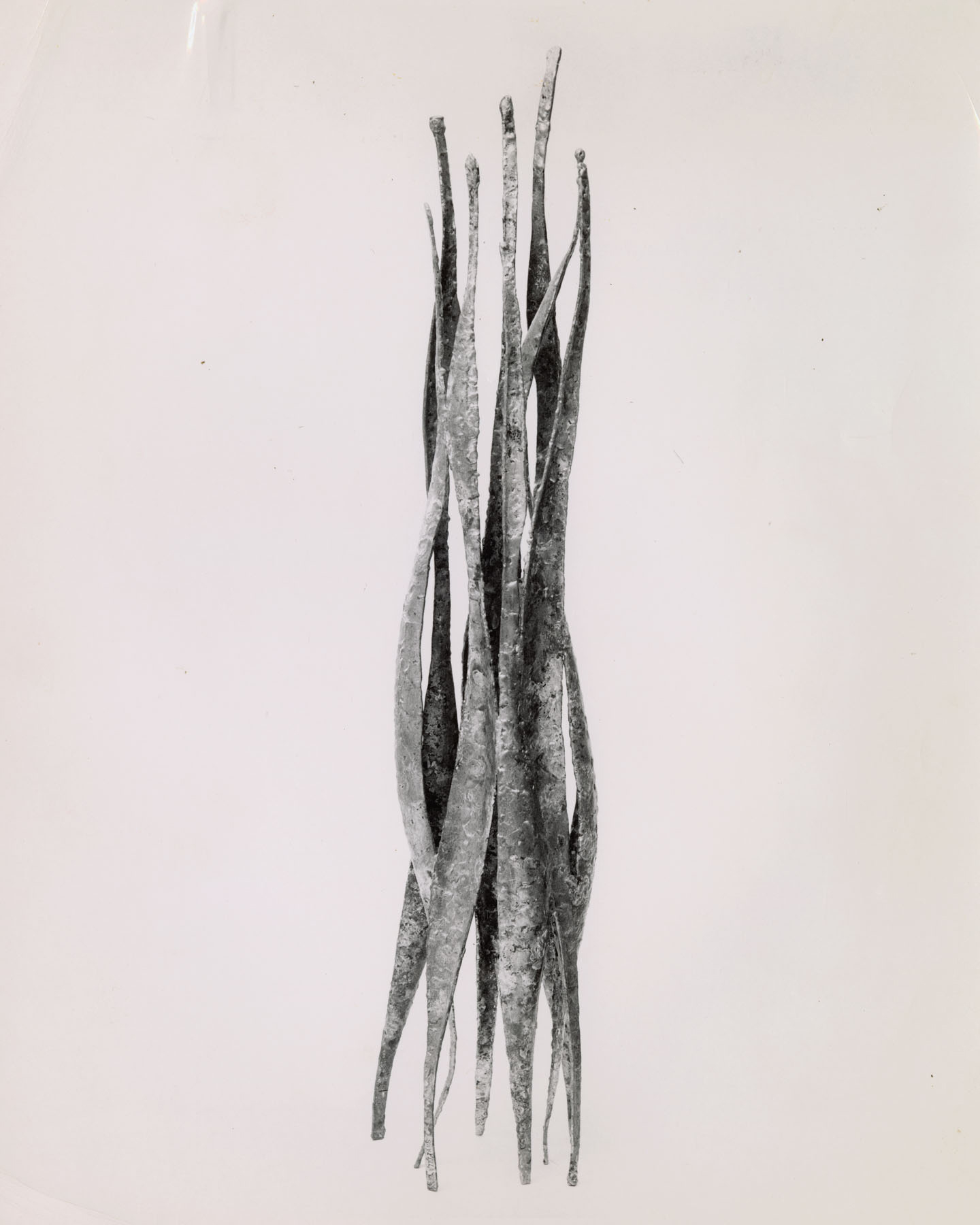

The FWAC granted Williams a solo show in late 1957. The director’s catalogue introduction commends Williams’s bravura, even with difficult materials, noting, “He is completely the master of his medium.”67 The show comprised six models and forty-two sculptures, from wood and stone carvings, through steel rod and plate welded constructions, and works of hammered brass and steel, to Williams’s first forays into bronze casting.

In truth, at the time of the FWAC show, Williams had only begun taking on technical challenges. Sometime after, he acquired a heliarc welder, a finicky tool that created aircraft-quality seams and could fuse nonferrous metals, and overhead handling equipment, which enabled him to take on ever-larger projects.68 Exploiting a variety of equipment and materials, he investigated all aspects of twentieth-century abstraction, staying abreast of developments through his friends, travel, and art publications.69 He ventured into found objects not long after assemblages and their evocations of entropy emerged on the West Coast (pl. 16). Torn-wax sculptures documented Happenings, as visitors to the studio ripped up sheets of wax and assembled them into forms that Williams later transferred to bronze (pl. 14). A 1964 lead piece resulted from a chance-driven deformation process. In the mid-60s he experimented with steel H beam and cold-rolled steel constructions (pl. 25 and see fig. 3.18). To these he added color and shine with automotive paints and coating processes, possibly responding to another West Coast craze, Finish Fetish.70 Unlike many sculptors, Williams rarely outsourced production.71 He upheld his standards even using equipment designed for speed and power over accuracy, provoking Vogel to observe, “As a craftsman, he had no peer. . . . Even when he sculpted with a chainsaw, it was with flawless precision” (fig. 4.16).72

Williams continued to participate in shows at the FWAC, although he did not have a warm relationship with Caldwell, and he seems to have actively disliked Caldwell’s successor, Raymond Entenmann, who was hired from PAFA in 1960. Boynton received a letter from Williams that must have expressed some frustration and replied, “How can Entenmann be worse than poor old Caldwell? I’m having trouble imagining. Actually the F.W. Art Center died some years ago and you ought to expect it to be stinking a bit by now.”73 Neither Entenmann nor Caldwell altered the FWAC exhibition practices, relying even more heavily on traveling shows to fill the spacious new building and interspersing them with periodic permanent collection, local collector, and local artist shows. Williams appeared in Sculptors of Texas in 1957 and featured prominently in a 1959 presentation of the Weiner collection. Works by Williams, Owens, and Medellín supplemented a 1961 show from MoMA on modern church architecture. In 1963, Williams installed elements of his large-scale Heritage of the Great Southwest series in the Art Center garden (fig. 4.17). On the other hand, Williams cut back on the time he offered the FWAC for demonstrations and committee work, and the artist’s subsidiary disbanded around 1957.

Fort Worth’s women artists remained a force at the Art Center. The juror for the 1960 Local, Walter Stuempfig of PAFA, was “impressed ‘by the extraordinary number of women painters in Fort Worth, and how good they are.’ . . . Usually, he explained, men painters are far better both in inspiration and execution than are women,” the Star-Telegram reported.74 Stuempfig did not comment on the sculptors. The FWAC made small advances in ethnic diversity. Sculptors of Texas consisted mostly of Houston artists and included Carroll H. Simms, a Black artist on the faculty of Texas Southern University. In 1962 the Art Center devoted a solo show to a Black artist for the first time with Illustrations by John Biggers, also a faculty member at Texas Southern. Beyond the walls of the Art Center, Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi made contemporary art part of the Fort Worth landscape when he installed the plaza of the new First National Bank building in 1960.

Under Caldwell, the FWAC expanded its class schedule and added instructors. Emily Guthrie Smith, Sellors, Trotter, and Utter formed a reliable core, while others came and went. In 1958 the center hired John Chumley, a realist painter from Tennessee, as its first non-local teacher.75 In retrospect, the appointment was an early sign of the center’s fading enthusiasm for local artists. TCU’s art department prospered and by 1962 numbered seven faculty. When Logan left in 1960, however, the department did not replace his expertise in sculpture, and sculpture courses merged with crafts and ceramics.76 An aspiring sculptor attended Sellors’s classes at the FWAC or visited Williams’s studio.

For experimentation and teaching advanced technique, Williams had no equal. After Gene Owens returned to Fort Worth with his MFA from the University of Georgia, he and Williams engaged in intensive study of the largely forgotten arts of sand and lost wax casting. In 1961 they set up a burnout kiln at Southwestern Brass Foundry in Fort Worth.77 Casting at Southwestern was a communal activity in which Sellors participated as did a new TCU BFA graduate, Ed Storms.78 Two recent arrivals to the area, painters Roger Winter and Joe Ferrell Hobbs, worked for Williams as studio assistants.79 Fellow artists deeply appreciated Williams’s encouragement. Vogel commented, “No one was more generous than Charles Williams in helping a friend or a young sculptor solve a problem or teach them how to cast their work. I have known him to drop his tools and go to the foundry and cast another’s work to teach him the process, never asking anything in return.”80 Boynton and Owens expressed similar sentiments.81

In 1957, Williams, along with Brownlow, Trotter, Utter, and a number of other area artists established the DFW Men of Art Guild (MoAG). Modeled on a similar cooperative in San Antonio, it aspired to provide mutual support and sponsor shows and awards to foster quality. In the fall, MoAG opened a space in Dallas, one of a growing number of contemporary art galleries in the area. The oil and Cold War defense industries drove prosperity, and museum exhibitions and sales had demonstrated the strength of the market. In 1959 in Fort Worth alone, Pauline Evans and Utter established Fifth Avenue Gallery, showing Williams and his peers as well as members of the Fort Worth Circle; the Weiners opened the Gallery of Modern Art, offering works by European artists; and Robert and Nancy Ellison inaugurated Ellison Gallery, concentrating on abstract expressionism. Electra Carlin refocused an existing operation and named it Carlin Galleries in 1960.

In Dallas, galleries for contemporary art remained rare through the early 1960s. McLean Gallery closed in 1954 following Betty’s divorce from Jock McLean and marriage to Tom Blake Jr.82 Vogel inherited McLean’s list of artists and in April 1955 opened Valley House Gallery. He worked with Joe Lambert, a Louisiana transplant who built a spectacularly successful landscape design business, to transform the gallery’s five acres in North Dallas into a garden suitable for a sculpture show; the inaugural took place in May 1960.83 Williams appeared regularly at the Spring Sculpture Shows, again alongside names like Moore and Picasso. Artforum’s review of the 1962 exhibition noted, “The most impressive pieces are by Fort Worth’s Charles Williams, who has upended a huge slab of granite and topped it with a balancing rock even huger and for a potent spell of mysterious playfulness.”84

Lambert became a champion of Williams, sponsoring a trip to Europe for Charles and Anita in 1963. He also offered to fund a move to New York City, still the epicenter of contemporary art. Williams declined.85 He explained to Karl:

If I were in the New York market—which is the only place I could really become a recognized sculptor—I would be deep in [a] political rat race. I just refuse to play and remain here where I will never be able to be anything but a third rate sculptor. It is true that I enjoy my seclusion and the easy pace, but there are dark moments when I feel that I haven’t given my all—that I have failed myself, my profession and my art by simply being afraid of that bitter stuff called failure.86

The “dark moments” may have been aggravated by Williams’s second severe heart attack, in late 1960. Williams’s eminence in the Texas art world and bustling commission business did not shield him from punishing self-critique.

Though he turned down New York, Williams’s exhibitions and commissions during this era expanded beyond Fort Worth to Dallas and Houston, as, in general, the ties between the cities’ art worlds grew closer. He added patrons in Dallas, such as high-end retail magnate Stanley Marcus and oil heirs John and Lupe Murchison.87 When Boynton took a job at the University of Houston in 1955, he provided introductions for Williams in that city. The next year, Williams won the only sculpture prize at the Gulf-Caribbean Exhibition at the MFAH with Eight (fig. 4.18), a work whose forms echo in some Boynton canvases of the period, such as Aftermath (fig. 4.19). At the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, director Jermayne MacAgy featured Williams’s work and Boynton’s in Pacemakers in 1957. In the events surrounding the exhibition, Boynton introduced Williams to sculptor Jim Love. They became scavenging partners, frequenting Gachman Metals, a Fort Worth recycling yard, in pursuit of future assemblages.88 Love later introduced Williams to filmmaker Roy Fridge and painter David McManaway, who joined the scrap metal hunt. Between 1958 and 1962, Houston’s New Arts Gallery gave Williams two solo shows; MacAgy’s groundbreaking Totems Not Taboo exhibition inspired Williams’s Ancient Warrior, which won first prize at the Texas General (fig. 4.20); and Houston’s new Sheraton Hotel commissioned a screen and fountain.

In 1957, the DFW Turnpike opened (now I-30 from downtown Dallas to Oakland Boulevard in Fort Worth), and a motorist could “breeze 30 miles through picturesque countryside” between the urban centers.89 For the operations building halfway between, Williams and Medellín, each city’s best-known modernist sculptor, collaborated on a mosaic that, somewhat ironically, humanized a space dedicated to the latest in high-speed ground transportation technology. The two men had known each other for several years and in 1956–57 jointly contributed to the interior of Temple Emanu-El in Dallas. They became such good friends that they and their wives took a road trip in the summer of 1959 through Texas and Mexico to Antigua, Guatemala.

Williams’s interest in ancient Mesoamerican cultures, particularly the Maya, undoubtedly informed the itinerary. During the 1960s, he made several trips to archeological sites in Mexico with Doc Keen, a local veterinarian and stunt pilot. In the archive, a manuscript of uncertain date documents considerable research into Maya art and architecture, especially techniques for sculpting in jade. He observed, “The Ancient Maya had no metal tools [making] their complete mastery of jade-carving an outstanding technical achievement.”90 In 1958 Williams received a block of Wyoming jade courtesy of New York gallerist Victor Hammer. He may have hoped to try his hand at carving in the manner of the Maya, but he never produced anything with it. The Weiners’ collection contained pre-Hispanic objects that may have sparked Williams’s curiosity, though museums and galleries in the area routinely exhibited similar works, much of it probably looted.

The 1959 road trip occasioned a derisive anecdote in Medellín’s memoirs in which Williams mistook a Chac Mool figure for a sculpture by Moore.91 Williams’s manuscript, however, almost certainly pre-dates the trip and includes a half-page discussion of the Chac Mool; he would not have mis-identified the maker.92 Whether prompted by Moore or the Maya, Williams’s massive 1958 Earth Mother, created for the Weiner garden, owes a clear debt to the form (fig. 4.21 and pl. 13).93 Nevertheless, the story reflects an underlying tension in the relationship between Williams and Medellín. During lunches, Karl reported, the two artists engaged in machismo-driven competitive hot-pepper consumption, the goal being to show no outward sign of discomfort. The challenges of travel through Texas and Mexico, particularly for a darker-skinned Otomí descendent like Medellín in the company of lighter-skinned Anglos, may have proved a strain. In any event, according to Karl, the friendship never fully recovered, much to the Williamses' dismay.94

At the time of the trip, Medellín worked for the DMFA, around which Dallas’s relatively conservative art scene revolved.95 After a controversy there over “communist art,” a group seeking an outlet for avant-garde work opened the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts (DMCA) in 1957.96 Boynton, McManaway, Williams, and others were frequent visitors and sometime exhibitors. When the DMCA hosted MoMA’s Art of Assemblage, director Douglas MacAgy (Jermayne’s ex-husband), added works by McManaway and Fridge to the show, which already included work by Love.97 McManaway joined Williams and abstract painter Toni LaSelle in Three Texas Artists shortly before the DMCA merged with the DMFA in 1963.

On the other end of the turnpike, in 1961 the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art (ACMWA) opened (fig. 4.22). When Amon G. Carter Sr. died six years earlier, his will provided funds for a museum to showcase his collection of works by Remington and Charles Russell “for the benefit of the public of Fort Worth and Texas.”98 Ruth Carter Johnson headed the effort. After rejecting architect Joseph Pelich, who had designed buildings for her father, and FWAC designer Herbert Bayer, she met Philip Johnson at a party in Houston. Ruth already knew of Johnson’s reputation, and a visit to his recent work on the University of St. Thomas campus led to an invitation to Fort Worth.99 Philip Johnson designed the building for a site overlooking downtown and across the street from the Fort Worth Art Center. Jermayne MacAgy organized the opening exhibition and wrote the catalogue. Ruth’s brother, Amon G. Carter Jr., ran the Star-Telegram as well as radio and TV stations, and the opening received extensive and highly complimentary media coverage. Until Mitchell A. Wilder arrived later in the year, the FWAC’s Entenmann also served in an administrative role for the ACMWA. Wilder quickly expanded the Carter beyond Russells and Remingtons, and by the middle of the decade, it exhibited contemporary artists alongside its western collection.

In 1964, Kay Kimbell died, setting in motion the creation of the Kimbell Art Museum just down the hill from the ACMWA. Like Carter, Kimbell got his start collecting art through the FWAA. The people leading the two new institutions, including Nenetta Burton Carter, Ruth Carter Johnson, Kay and Velma Kimbell and his niece Kay Fortson, helped guide the FWAA and learned as it grew from a library gallery to a stand-alone museum. That evolution owed some part to the contributions of Williams and his circle.

A Legacy of Art

Williams’s third serious heart attack, in March 1966, proved fatal. He is buried in Wichita, Kansas, next to Louise. Fort Worth remembers him with a handful of his sculptures in public and private collections.

A more enduring legacy, however, resulted from Williams’s long-time promotion of artistic excellence and cooperation. Up-and-coming artists in Fort Worth found an infrastructure of classes and community to support their development, make introductions, and promote sales. Scott and Stuart Gentling, for example, took art classes at the FWAC. Instructor Emily Guthrie Smith showed Scott’s work to a visiting artist, who secured an invitation for Scott to study at PAFA. Scott had a solo show in the Art Center Members Lounge in 1964. Anne Windfohr brought the young man to the attention of Vogel, who gave Scott a solo show in March 1966. Stuart’s career followed Scott’s, albeit on a slightly different path.100 The advocacy of Williams, and of the Fort Worth Circle artists before him, helped build and sustain the institutions that launched the Gentlings’ and others’ careers.

In spring 1965, a friend of the Gentlings named James J. Meeker, whose father Julian had commissioned sculptures from Williams, wrote an article for the Star-Telegram on the opening of a new building for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). He called LACMA’s director, Richard F. Brown, “one of the most accomplished art museum directors in the United States.”101 By the end of the year, the Kimbell Art Foundation had hired Brown as director. Brown arrived in Fort Worth in early 1966 and immediately went to work on a building for the Kimbell collection. After considering both Philip Johnson and Edward Larrabee Barnes, by late spring he was in conversations with Louis Kahn. The Kimbell Art Museum opened October 4, 1972 (fig. 4.23).102

At the FWAC, Entenmann resigned in 1966. Although his replacement, Donald Burrows, stayed only two years, he added Picasso’s Femme couchée lisant (Reclining Woman Reading) to the permanent collection by outbidding suitors from London, New York, and Los Angeles during the first internationally televised art auction.103 Burrows’s successor, Henry T. Hopkins, a curator from LACMA, took over in June 1968. Under Hopkins, exhibitions and programs at the FWAC mirrored the national fascination with abstract expressionist, pop, and conceptual art, and artists like Robert Irwin, Robert Rauschenberg, and Ed Ruscha made regular appearances on the Fort Worth art scene. In 1970, Hopkins organized the US Pavilion at the 35th Venice Biennale, jointly sponsored by the FWAA and the Smithsonian.104

While the Biennale and Picasso purchase raised international awareness of Fort Worth and its Art Center, attention to hometown artists waned. The last of the annual solo shows for a Fort Worth artist took place in October 1966 and featured Emily Guthrie Smith’s work. The Local continued until the mid-1970s. Based on the Local’s successful proof-of-concept, private galleries entered the business.105 They eventually supplanted the Art Center’s event altogether.

The shift away from local talent coincided with a decline in presentation of work by women artists. Group shows still included women in reasonable numbers. The share of “one-man” shows devoted to women, however, plummeted.106 In the 1940s and early 1950s, half of the FWAC’s infrequent solo shows went to female artists. As the Center mounted more solo exhibitions, fewer and fewer went to women: between 1957 and 1967, women received about one of every six solo exhibitions, and only three had solo shows during the entire decade of the 1970s, with none from 1974 to 1979.107 Similarly, most of the solo exhibitions at the ACMWA and the Kimbell Museum went to men, although the Carter organized a Georgia O’Keeffe retrospective and an exhibition of Clara MacDonald Williamson’s works in 1966 and nine solo shows of works by woman photographers between 1966 and 1978, including Dorothea Lange, Laura Gilpin, and Barbara Morgan.108

The drop at the FWAC happened despite having a board of directors that was more than half women, among them the formidable Anne Burnett Tandy (formerly Windfohr) and her daughter Anne Windfohr Meeker (later Marion), as well as Velma Kimbell and Kay Fortson. Betty Guiberson (formerly McLean) served on the Art Association’s advisory board. Kimbell and Fortson also played important roles at the Kimbell Foundation. Ruth Carter Johnson, the visionary behind the Amon G. Carter Foundation and the ACMWA, represented the City Art Commission at the FWAA.109

A 1967 press release from the Amon Carter Museum announced it would no longer limit itself to western art but expand its mission to encompass the entire United States, arguing that “to understand the West the East also must be studied.”110 The three art museums, whose directors had known each other in Los Angeles and whose board members had years of shared history, soon agreed on boundaries to avoid competing for exhibitions or acquisitions: The FWAC focused on art of the twentieth century regardless of geography, while the other two museums divided pre-twentieth century art between them along geographic lines, the ACMWA concentrating on American art and the Kimbell on art outside of North America.111

The spirit of cooperation, however, did not prevent the loss of an unfortunate number of mid-century works. The Williams/Medellín mosaic at the Turnpike operations center fell to a bulldozer, and Noguchi’s installation at the First National Bank was largely dismantled. Williams’s door pulls for All Saints Hospital disappeared during a renovation.112 Most of the Weiners’ sculpture collection went to Palm Springs when the city of Fort Worth failed to take action to acquire the garden. Earth Mother now resides on the campus of the University of North Texas in Denton.

A close-up of Charles T. Williams manipulating a mallet and chisel graced the catalogue cover for his solo show at the FWAC in 1957, but he had a hand in shaping more than wood, stone, and metal (fig. 4.24). Sharing materials and expertise, he formed artists and others who passed through his studio. Working behind the scenes, he connected people and ideas to leave a distinctive impression on the modernist impulse in Fort Worth.

NOTES

-

Hardin-Simmons University, The Bronco, Yearbook of Hardin-Simmons University (Abilene, TX: Hardin-Simmons University, 1941), texashistory.unt.edu. ↩︎

-

He also completed non-commissioned officer and carpentry training there. ↩︎

-

R.S. Walsh Jr., Chief, Personnel Branch, to Charles T. Williams, August 7, 1947, in Army Corps of Engineers Records [3] folder, Charles Truett Williams Papers, Amon Carter Museum of American Art (hereinafter, “ACMAA Williams Papers”). ↩︎

-

“Forced Retirement of Librarian Is Indicated,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 15, 1938, 1, 4. ↩︎

-

Reba Oglesby, “History of the Fort Worth Art Association” (Master’s Thesis, Texas State College for Women, 1950), 124. ↩︎

-

Confusingly, the FWAA used the 1940 show as the starting point for numbering subsequent Local exhibitions, although the Star-Telegram called the 1939 show “the first annual” and the 1940 show the “second annual.” (Ida Belle Hicks, “Art Prize Winners Announced,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 4, 1939, 20; and “First Prize Winner in Local Artists Show” (photo caption), Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 8, 1940, 9). ↩︎

-

Pauline Naylor, “Public School Art Work to Be Shown,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, February 24, 1929, 7. The report did not discuss curricula for Black schools. ↩︎

-

Scott Grant Barker, “An Unconventional Vision: Remembering the Fort Worth Circle,” in Intimate Modernism: Fort Worth Circle Artists in the 1940s (exhibition catalogue), ed. Jane Myers (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 2008), 12–13; Kendall Curlee, “Helfensteller, Veronica,” Texas State Historical Association, June 11, 2020, www.tshaonline.org. See also the artists’ biographies in Intimate Modernism, 184–94. ↩︎

-

Kendall Curlee, “Reeder, Edward Dickson,” Texas State Historical Association, June 1, 1995, www.tshaonline.org. ↩︎

-

Donald S. Vogel, Memories and Images: The World of Donald Vogel and Valley House Gallery (Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 2000), 57–60. ↩︎

-

William Kelly Fearing, “Memories and Reflections of People and Artists, Events, Actions and Happenings, during My Days and Nights as an Artist in Fort Worth, Texas 1943–1947,” in First Light: Local Art and the Fort Worth Public Library 1901–1961 (exhibition catalogue) (Fort Worth: Fort Worth Public Library, 2001), vi. ↩︎

-

The Artists Guild provided a sales outlet until it closed in 1939. Other venues included Bandy’s, and Collins and Dow frame shops. Various artists’ clubs also held periodic exhibitions and sales (Scott Grant Barker, “New Deal Entrepreneurs: The Fort Worth Artists Guild Opens a Gallery,” in Planned, Organized and Established: Houston Artist Cooperatives in the 1930s (exhibition catalogue) (San Angelo, TX: Center for the Advancement and Study of Early Texas Art, 2017), 26–29; Ibbie Bryan, “Art Notes,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, February 7, 1936, 27). ↩︎

-

Fearing, “Memories and Reflections.” ↩︎

-

Katie Robinson Edwards, “Gene Owens Oral History Transcript” (unpublished manuscript), 2008, 43. ↩︎

-

Sam Cantey III, “Fort Worth,” in Texas Painting & Sculpture: The 20th Century (exhibition catalogue) (Dallas, San Antonio, Austin, Fort Worth, and Lubbock: Pollock Galleries, San Antonio Museum Association, University Art Museum, Amon Carter Museum, The Museum, 1971), 21. ↩︎

-

Leon Wilson, “The History of the TCU Art Department Through 1969” (MFA Thesis, Texas Christian University, 1970), 46–116, TCU Art History Department Archives. ↩︎

-

Wilson, 85; Texas Woman’s College, TXWOCO, Yearbook of Texas Woman’s College (Fort Worth: Texas Woman’s College, 1920), 12, texashistory.unt.edu. Wilson says Ziegler joined TWC in 1917 based on an interview with Ziegler in 1966. TWC was Texas Woman’s College until 1935. ↩︎

-

Texas Wesleyan College, TXWECO, Yearbook of Texas Wesleyan College (Fort Worth: Texas Wesleyan College, 1943), texashistory.unt.edu. See also the yearbooks for 1944–1947. ↩︎

-

Reflecting the practice of the era, this essay refers to “men” and “women,” understanding that to do so overlooks many nuances of gender identity and sexual orientation. “Black,” “White,” and other terms related to ethnic heritage similarly elide fascinating complexities of culture and experience that are unfortunately beyond the scope of this discussion. ↩︎

-

“Fort Worth Art Association Leaders Named,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 6, 1946, 2. ↩︎

-

Richard F. Selcer, A History of Fort Worth in Black & White: 165 Years of African-American Life (Denton, TX: UNT Press, 2015), 452, 475. A full understanding of segregation and integration of the library and art association requires further research. Some civic facilities were open to non-Whites on select days. In September 1929, when the National Association of Negro Musicians held a conference in Fort Worth, Scheuber gave the group a tour of an art exhibition at the library. In 1963, an American Library Association report on library desegregation held that “Fort Worth [has] equal facilities.” (“J. Wesley Jones Re-elected,” Chicago Defender, September 7, 1929, 2, and “Integrated Libraries,” Chicago Daily Defender, January 14, 1963, 12.) A Black person was appointed to the library board in 1961, by which time, Selcer notes, the library department “had been quietly integrating for several years.” ↩︎

-

Oglesby, “History of the FWAA,” 99–101. ↩︎

-

“Application for Federal Employment,” June 7, 1948, 1, in Army Corps of Engineers Records [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers; Katie Robinson Edwards, “Jack Boynton Oral History Transcript” (unpublished manuscript), 2007, 4; Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], November 9, 1947, 4, in Correspondence - Lila [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], October 5, 1947, 2, in Correspondence - Lila [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

[Charles T. Williams] to Lîlá [Ménard] (draft letter), September 17, 1948, in Manuscript - Puppet Show folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Charles T. Williams, “[Script for Humble Oil commercial]” and “[Script for Pearl Beer commercial],” both [ca. 1948] in Manuscript - Puppet Show folder, ACMAA Williams Papers; Charles to Lîlá, September 17, 1948. ↩︎

-

Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], November 4, 1947, in Correspondence - Lila [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Scott Grant Barker, “John Wilbur Erickson” (unpublished manuscript), 2022, 1. ↩︎

-

Texas Christian University, “Fine Arts Building and Auditorium” (press release), September 9, 1949, repository.tcu.edu. The auditorium was dedicated to Ed Landreth shortly after the building opened. Later, the entire building became Ed Landreth Hall. ↩︎

-

“Drowning Death Toll Brought to 8” and “Estimates Set $12,000,000 Flood Damage,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 18, 1949, 1. ↩︎

-

Wilson, “History of TCU Art Department,” 156–57. ↩︎

-

Wilson, 137–38. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Boynton Oral History,” 4. ↩︎

-

Lîlá [Ménard] to [Charles T. Williams], September 13, 1949, in Correspondence - Lila [1] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

“Forest Park Tree Award-Winning Carving Now,” [Possibly Fort Worth Press], [October 1950], clipping in microfilm reel 1800, Charles T. Williams Papers, 1949–1966, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (hereinafter, “AAA Williams Papers”). ↩︎

-

Eleventh Annual Texas Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture (exhibition catalogue) (Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio: Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Witte Memorial Museum, 1949–50), texashistory.unt.edu. ↩︎

-

Charles T. Williams, “The Design and Execution of a Fountain Sculpture” (MFA Thesis, Texas Christian University, 1955), 26. Logan was not among the faculty members who approved Williams’s thesis. ↩︎

-

Scott Grant Barker, “Sellors, Evaline Clarke,” Texas State Historical Association, February 8, 2022, www.tshaonline.org. ↩︎

-

Karl Williams, conversation with the author, April 12, 2022. ↩︎

-

“FWAA Leaders Named,” 2; Nedra Jenkins, “Art Association Hears Gloomy Financial Report,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 4, 1954, 7; 20th Century Paintings (exhibition catalogue) (Fort Worth: Fort Worth Art Association, 1966). ↩︎

-

Nedra Jenkins, “Art Association Will Present ‘Wildcat’ Show,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 26, 1951, 44. ↩︎

-

Texas Wildcat (exhibition catalogue) (Fort Worth: Fort Worth Art Association, 1951); Nedra Jenkins, “Texas Art Preview to Be Seen Here April 29,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 20, 1952, 54. ↩︎

-

Nedra Jenkins, “Art Plan Is Extended into Business Field,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, February 17, 1952, 27. ↩︎

-

“[Committee Roster],” ca. 1956, in microfilm reel 1803, AAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

“Artists to Form Subsidiary of Fort Worth Art Association,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, October 10, 1951; “[Artists Subsidiary Meeting Minutes],” [ca. 1952]; “[Artists Subsidiary Meeting Minutes],” May 4, [1952 or 1953]; “[Artists Subsidiary Meeting Minutes],” January 29, 1953; “[Artists Subsidiary Meeting Minutes],” May 25, 1953; “[Artists Subsidiary Meeting Minutes],” April 11, 1956; all in microfilm reel 1803, AAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Owens Oral History,” 63. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, 3–4. ↩︎

-

Charles T. Williams, “Sculpture Log 1952–1964,” 7, ledger in ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Boynton Oral History,” 15–16. Only eight artists of the 57 in the exhibition did not come from the East or West Coast. The Trotter work in the show, Two Cities, was loaned by Ted and Lucile Weiner (Younger American Painters (exhibition catalogue), (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1954), www.archive.org). ↩︎

-

Christopher Ohan, “Ruth Carter Stevenson Oral History Transcript” (unpublished manuscript), 1999–2000, 22–23, Amon Carter Museum of American Art Oral History Archives. ↩︎

-

[Charles T. Williams] to Dan [Defenbacher] (draft letter), [ca. October 1955], in microfilm reel 1800, AAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

D.S. Defenbacher to Charles Williams, May 25, 1955, in microfilm reel 1800, AAA Williams Papers. “Out here” refers to Oakland, California. ↩︎

-

Sam Cantey III, “Store’s Art Exhibition Features Local Talent,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 24, 1963, 44. ↩︎

-

The Eighteenth Annual Texas Painting and Sculpture Exhibition (exhibition catalogue) (Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio: Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Museum of Fine Arts, and Witte Memorial Museum, 1956), texashistory.unt.edu. ↩︎

-

Nedra Jenkins, “Texas Sculpture Again Fades into Background,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, November 4, 1956, 60. ↩︎

-

[Sculptors] to Jerry Bywaters, Director, Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (draft letter), October 8, 1956, in microfilm reel 1800, AAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Scott Grant Barker, “Karl Williams Oral History Transcript” (unpublished manuscript), 2021, 5, Amon Carter Museum of American Art Oral History Archives. ↩︎

-

Cantey III, “Fort Worth,” 21; Katie Robinson Edwards, Midcentury Modern Art in Texas (Austin: University of Texas, 2014), 211. ↩︎

-

The Sculpture Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Ted Weiner (exhibition catalogue) (Fort Worth: Fort Worth Art Association, 1959); Williams, “Sculpture Log 1952–1964,” 56. The collection also included works by a handful of women artists as well as by Logan and Sellors. ↩︎

-

Williams, “Sculpture Log 1952–1964,” 97, 103, 110, 125. ↩︎

-

Williams, 18–19. ↩︎

-

Williams, “Fountain Sculpture,” 9–11. ↩︎

-

Charles T. Williams to Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Architects (draft letter), May 24, 1955; Charles T. Williams to Eero Saarinen & Associates (draft letter), May 24, 1955; both in microfilm reel 1803, AAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Williams, “Sculpture Log 1952–1964,” 45, 51, 61, 62. ↩︎

-

Rual Askew, “Stage Is Set for Monument,” Dallas Morning News, March 22, 1959, 78. ↩︎

-

“Statues Ok’d at Love Field,” Dallas Morning News, July 18, 1959, 1. ↩︎

-

The Sculpture of Charles Williams (exhibition catalogue) (Fort Worth: Fort Worth Art Association, 1957). ↩︎

-

Karl Williams, email to Katie Robinson Edwards, March 27, 2022. ↩︎

-

Barker, “Karl Williams Oral History,” 8; Williams, “Sculpture Log 1952–1964”; Charles T. Williams, “Sculpture Log 1965–1966,” ledger in ACMAA Williams Papers; Karl Williams, conversation with the author, September 17, 2021. ↩︎

-

Williams, “Sculpture Log 1965–1966.” ↩︎

-

“Sculptor’s Remains Interred in Wichita,” 1966, clipping in Clippings folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Donald Vogel, “Foreword,” in Charles T. Williams, Retrospective with Friends (exhibition catalogue), ed. Diana R. Block (Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 1998), ix. ↩︎

-

Jack [Boynton] to Charlie and Anita [Williams], December 1, 1960, 1, in microfilm reel 1801, AAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Lloyd Stewart, “Art Show Judge Is Impressed,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 4, 1960, 75. ↩︎

-

“Tennessee Artist Named to Art Center Teaching Staff,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 20, 1958, 30. ↩︎

-

Wilson, “History of TCU Art Department,” 200–204. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Owens Oral History,” 5, 6, 28; Williams, “Sculpture Log 1952–1964,” 72; Diana R. Block, “Introduction,” in Block, Charles T. Williams, Retrospective with Friends, xv. ↩︎

-

Karl Williams, conversation with the author, September 17, 2021; Robinson Edwards, Midcentury Modern Art in Texas, 288. ↩︎

-

Paul Rogers Harris, “Contemporary Art and Texas Artists in the 50s and 60s,” in Block, Charles T. Williams, Retrospective with Friends, 26. ↩︎

-

Vogel, “Foreword,” ix. ↩︎

-

Robinson Edwards, “Boynton Oral History,” 4; Robinson Edwards, “Owens Oral History,” 72. ↩︎

-

Vogel, Memories and Images, 102–3. ↩︎

-

Vogel, 120; “Partial Exhibition History,” Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden, accessed April 22, 2022, www.valleyhouse.com. ↩︎

-

Rual Askew, “Reviews - Dallas,” Artforum 1, no. 2 (July 1962): 44. ↩︎

-

Karl Williams, conversation with the author, April 12, 2022. ↩︎

-

Charles [T. Williams] to Karl [Williams], January 10, 1966, in Correspondence - General [2] folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Barker, “Karl Williams Oral History,” 11–12. ↩︎

-

Barker, 7. ↩︎

-

Quentin McGown, Fort Worth in Vintage Postcards (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 115. ↩︎

-

Charles T. Williams, “[Essay on Maya culture],” n.d., 24–25, in Manuscripts folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Stephanie Lewthwaite, “Modernism in the Borderlands: The Life and Art of Octavio Medellín,” Pacific Historical Review 81, no. 3 (August 2012): 361. ↩︎

-

Williams, “[Essay on Maya culture],” 19. ↩︎

-

Block, “Introduction,” xv; Thomas Motley, “The Sculptural Works of Charles T. Williams,” in Block, Charles T. Williams, Retrospective with Friends, xi–xvi. ↩︎

-

Karl Williams, conversation with the author, April 12, 2022. ↩︎

-

Mark A. Castro, Octavio Medellín: Spirit and Form (exhibition catalogue) (Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 2022), 21. ↩︎

-

Kendall Curlee, “Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts,” Texas State Historical Association, June 20, 2019, www.tshaonline.org. ↩︎

-

William C. Seitz, The Art of Assemblage (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1961), 160; Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts, The Art of Assemblage (unpublished exhibition checklist), 1962, 1, 2, 9, texashistory.unt.edu. ↩︎

-

“Carter Estate Left for Public’s Benefit,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 7, 1955, 1. ↩︎

-

Ohan, “Stevenson Oral History,” 32–33. ↩︎

-

Janelle Montgomery, “Brothers in Arts: A Gentling Chronology,” in Imagined Realism: Scott and Stuart Gentling (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 2021), 244. The entry on Scott’s introduction to Vogel incorrectly refers to Anne Burnett Windfohr (later Marion); it was her mother, Anne Burnett Windfohr (later Tandy) who made the introduction. ↩︎

-

James J. Meeker, “Los Angeles to Open Largest Art Museum,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 28, 1965, 18. ↩︎

-

“Kahn’s Museum: An Interview with Richard F. Brown,” Art in America, September–October 1972, 44, 46. ↩︎

-

Mark Thistlethwaite, “Pablo Picasso,” in Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth 110 (Fort Worth: Fort Worth Art Association, 2002), 274. ↩︎

-

More than half of the invited artists, including Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and Robert Motherwell, declined to participate in protest of the Vietnam War (Frederic Tuten, “Soggy Day in Venice Town,” New York Times, July 12, 1970, 87). ↩︎

-

Cantey III, “Fort Worth,” 21. ↩︎

-

The local press during this era referred to solo shows as “one-man” regardless of the gender of the presenting artist. ↩︎

-

This analysis is based on exhibition history records in the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth archives. ↩︎

-

Amon Carter Museum of American Art Exhibition Archives. ↩︎

-

20th Century Paintings. ↩︎

-

Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, “Image to Abstraction” (press release), August 31, 1967, 1, Amon Carter Museum of American Art Exhibition Archives. ↩︎

-

Carolyn Aiken, “Third Museum to Culminate Cultural Plan,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 11, 1969, 127, 132. ↩︎

-

Karl Williams, conversation with the author, April 12, 2022. ↩︎