A Moment of Time Caught in Grooves and Dimensions

- Jonathan Frembling

An artist’s archive is a time capsule or snapshot of a life’s multidimensional legacy, like the sole surviving photograph from an obscure happening that makes a single moment the permanent and definitive version of the event. The archive, then, serves as a repository to gather into one place the many items that make up a life’s snapshot, forming the fodder upon which the scholarship of that life is built—especially when all the contemporaneous actors in the events are gone. The archive reveals or obfuscates by turns, being the sum only of what has survived, and such “survivors” are prime examples of time’s uncertainty; no matter how carefully the archival items are gathered, what survives and what does not is often determined by chance. Chance shapes the narrative as much as who is telling the story.

While artists may diligently save important mementos of their lives, these carefully curated moments, gathered for posterity, in the end may not be of interest to the researcher. Imagine, for example, the contents of the hope chest at the foot of a grandparent’s bed that contains deeply personal items from life, which, once the person has passed and these associations are lost, lose all meaning. Rather than being held up as notable relics informing a notable life, they become part of antique shop displays of the faded and forlorn relics of countless, nameless lives. An archive also contains what is gathered after the artist is gone by well-intentioned third parties endeavoring to preserve anything that might illuminate the artist’s life. Such surviving artifacts are often bundles of random mail left on a table, boxes of old receipts saved in case of an IRS audit, or leavings from the last projects that were intended to be finished at some point in a future that will not come. Whether by plan or happenstance, these items inevitably shape the scholar’s narrative.

Such is the case with the Charles Truett Williams Papers in the archives of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. The raison d’être of the essays that follow is to take these archival materials and build upon them, to study and organize them and then stitch them together into a story. This starts with the Museum’s mission to share the artists archives we have through exhibitions, fellowships, and publications, which together provide an opportunity to encounter these otherwise hidden collections and to gain introduction to these artists on their own terms and in their own words—not just through the art they make, but in what they write, what they chose to keep, and what fortune allowed to survive. This mandate is particularly important with an artist like Charles T. Williams (1918–1966), who was such a vigorous part of the art world of his day—especially in Fort Worth—whose career was tragically short, and for whom there is little extant scholarship (fig. 2.1).

The Williams Papers serve as a textbook example of the opportunities to create engaging scholarship, as well as the challenges of doing so. The papers only amount to about four and a half linear feet of material—five boxes. However, the descriptor “Papers” obfuscates the range of its contents. There are letters and manuscripts here, doodles and sketches, photos and artifacts from birth to after death. Such seemingly bland items, obscured behind archives jargon, do not reveal on their surface the depths of what can be discovered in their collective portrait of the artist—or conversely, the maddening questions they raise by what is missing.

The basic details of Williams’s personal life are found in the papers; there are the legalistic standards of birth and marriage certificates, diplomas and passports. His professional career can similarly be broadly sketched from the catalogues of exhibitions and newspaper clippings, all easy to find now online, though no researcher will complain that they were saved and are now preserved. But such items do not make good history or tell the fuller story.

Indeed, the papers have surprisingly little that capture Williams’s voice. There are few examples of his letters, leaving sizable portions of his life and words unrecoverable. We have almost nothing from his childhood and young adulthood before World War II. We learn he was born in rural Texas to a small, conventionally religious family of masons, that he served as a draftsman during the war but wrote very little about what he encountered in Europe. The letters that survive capture his deep affection for his young wife, Louise, and a single line about what he had witnessed of war upon encountering a freed POW: “(He) is trying to get used to life again. Just sits and stares into space, is awfully jumpy and nervous. Tells about people starving—eating grass and wood. About people getting killed—and he’s telling the truth.”1

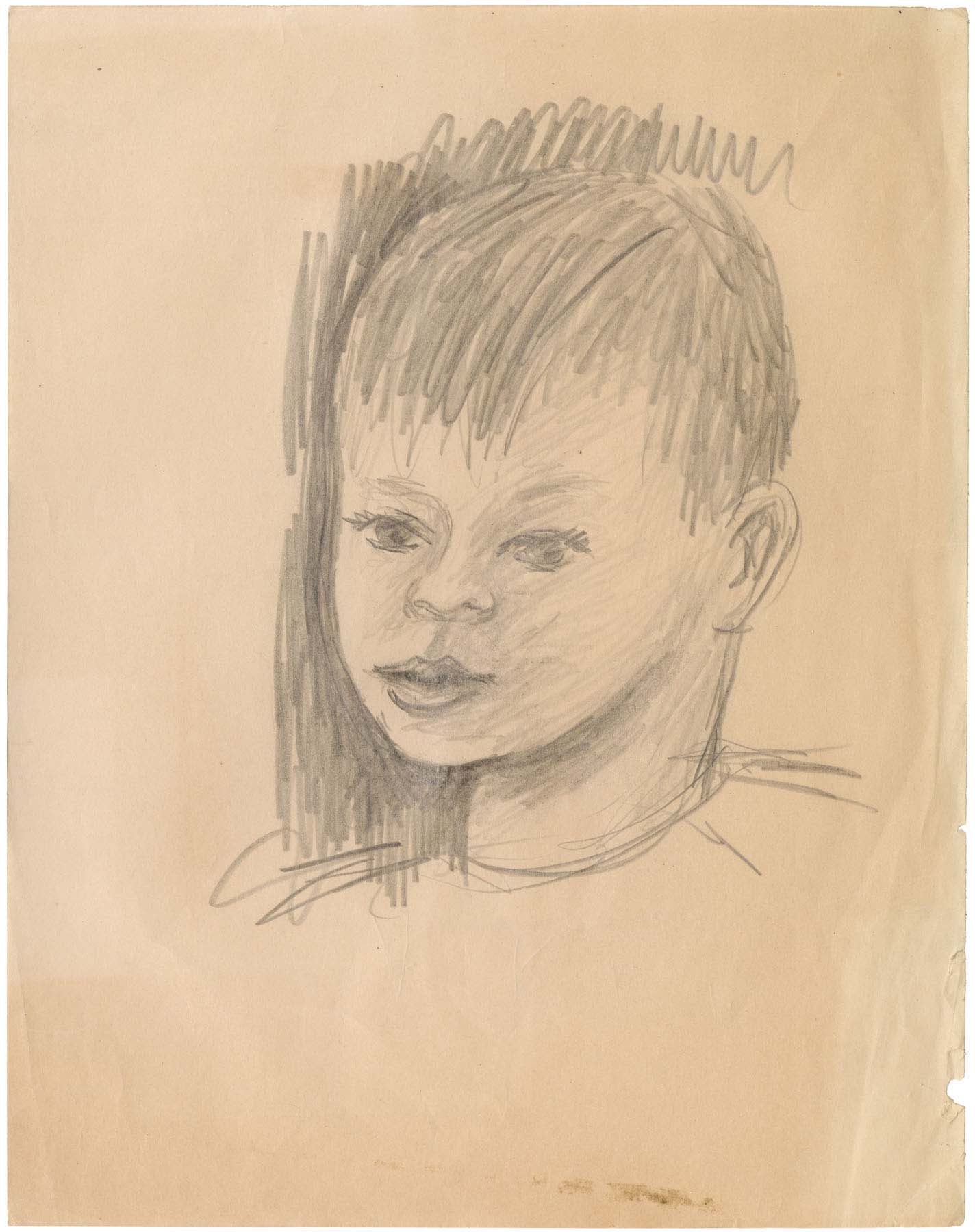

There are also gaping voids in the papers around Williams’s personal life following the war. Louise, the mother of his only child, died of pneumonia in 1947, but there is no record of what he felt and thought. Similarly, nothing from his courtship and marriage to his second wife, Anita, appears in the papers.2 He also kept very little pertaining to his relationship with his son, Karl (fig. 2.2).3 What does come into clear focus through a sheaf of letters—unlike anything else in the papers in quantity and duration—is evidence of an intense friendship struck up with Parisienne Lîlá Ménard during the war that would continue until Williams’s death.4 Beyond a handful of other letters from his kin asking him to join the family masonry business, the correspondence in the papers turns to purely professional matters.

Instead of joining his father and brother as masons, Williams opted for the Corps of Engineers, working on architectural embellishments in addition to his engineering work, which over time led him toward architecturally sculptural art and commissions.5 Even though he was not a writer by training, he could be eloquent, especially on matters of the arts and their importance to society.

Sculpture and other forms of art have been removed from our daily lives and must be sought out in places set aside exclusively for their appreciation. With the result that instead of enriching the lives of many, art has become through inaccessibility, meaningless to all but a small portion of the population. This separation of the product of man’s artistic creation from the life of the community is a phenomenon which has not always existed in the past. The ancient Greek agora, an everyday meeting place of the people, was enhanced by sculpture, murals and mosaics. [In] the medieval marketplace, the focal point was the fountain, often a fine piece of sculpture.6

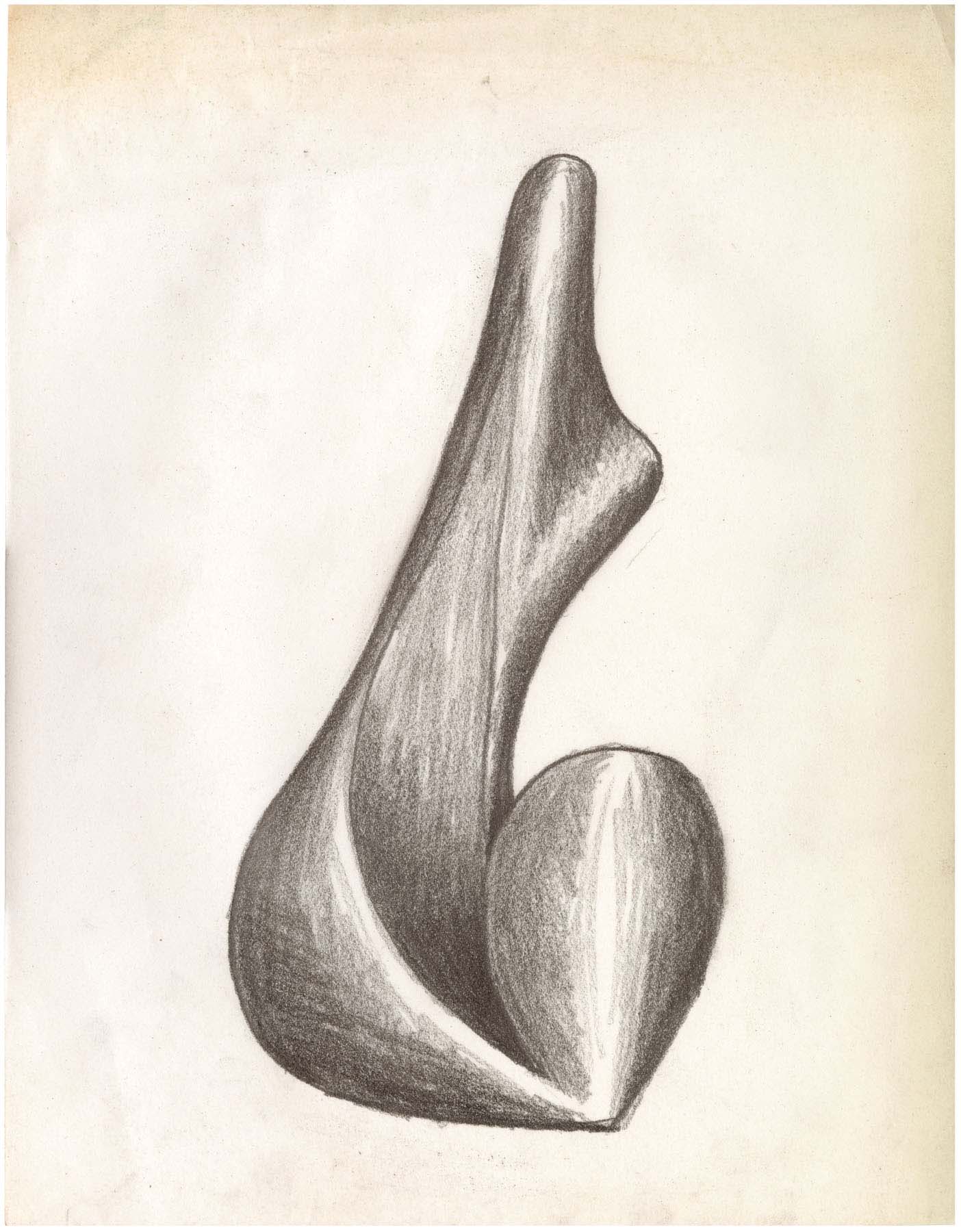

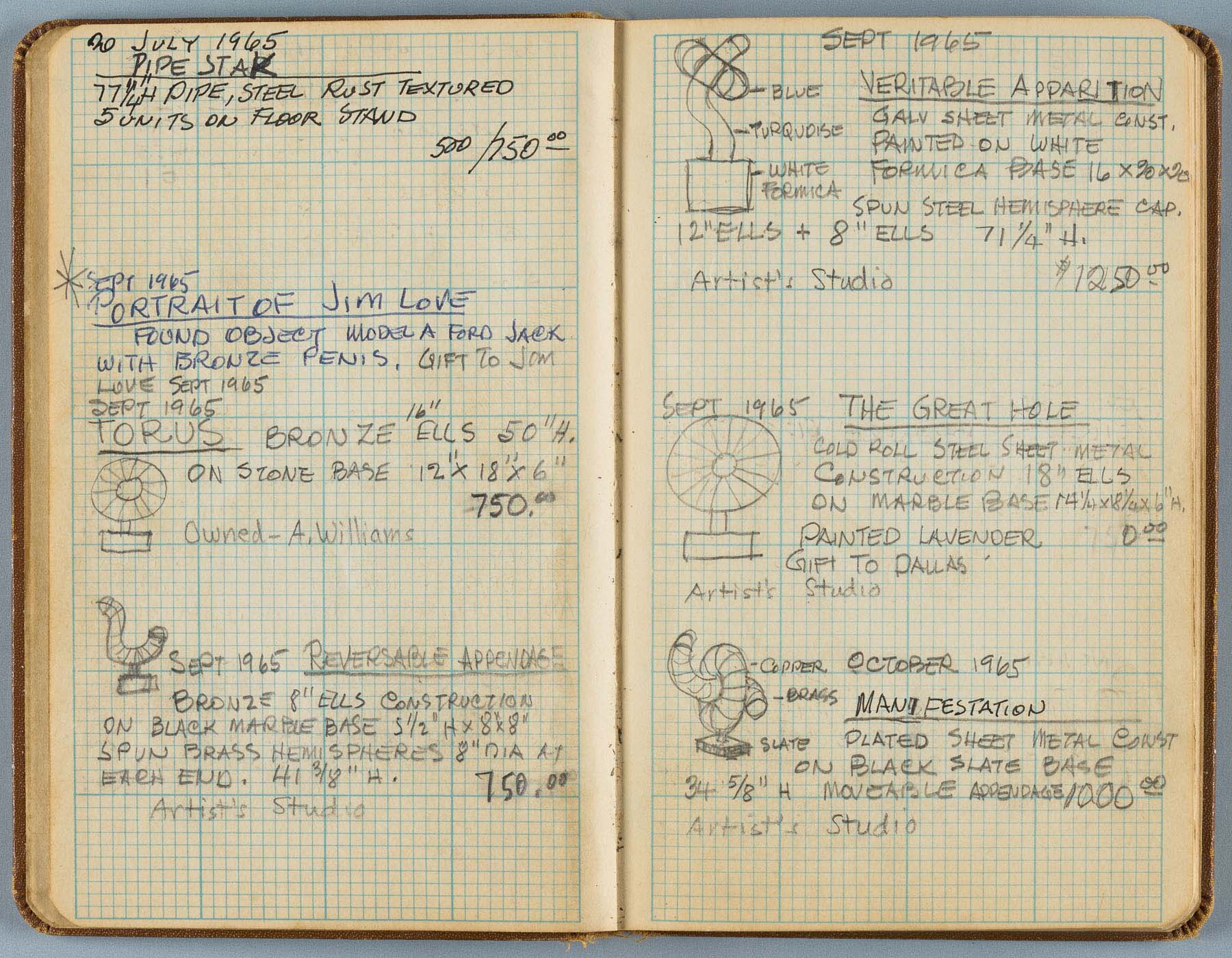

Art was not only Williams’s chosen profession, it was the core of his being, so it follows that 80 percent of his papers are about his art, forming the clear bulk of the archive. These materials convey his nature—both through what is observable in the material and by its volume. There are beautifully engraved linoleum blocks for his creative and playful prints, as well as hundreds of sketches and photographs that provide an irreplaceable summation of his artistic technique and overall output (fig. 2.3). Within these sketches are examples of his process, his working through ideas in iterative tinkering with motifs and designs leading to final formalized sketches. Included in the photographs are snapshots of final works, a number of which remain unlocated or lost, making these images the only records of their existence. A trained engineer, Williams meticulously logged each of his compositions and, in many instances, who their buyers were along with sales price, providing an expansive accounting of this aspect of his career (fig. 2.4).

While this summation of his art making is vital, something important about the man would go missing without observing closely the blocks, sketches, photos, and sculptures that form his art. His work brought out a deep spirituality and innate passionate eloquence, hinting at his natural charisma and force of personality. His spirituality was at odds with the larger conservative outlook of midcentury Texas—he was an unashamed atheist but one who acknowledged the unique magic of making art, considering artists as something more akin to a shaman than a craftsman, even if this outlook at times cost him commissions to his peers and rivals, such as Charles Umlauf.7 It gave his art a delightful playfulness, especially as he progressed from a journeyman learning technique to an accomplished artist. In his later work, there is a much greater emphasis on found-object compositions that tap into the mystery of chance leading an artist to inspiration—turning the everyday into art.

While art was fundamental to Williams’s character, that did not translate into serious art making. This is elegantly expressed within the archive and extends the motif of Williams as shaman or artistic spirit guide, which is made clear in the hundreds of photographs in the papers of parties mixing frivolity with artistic and intellectual mingling—an example being “The Game” played at these parties, wherein one artist began a composition and another finished.8 More happened here than partying; The Game was an expression of the French Existentialist viewpoint, championed by Williams, of living for today, forged during a life lived with intensity, leavening in ideas new to Texas that he gathered in his time in Europe during the war. This milieu is glimpsed in the photographs of artists gathered in his studio—Williams leading a collaborative artistic environment that created art and lived for the moment.9

The Charles Truett Williams Papers provide a singular opportunity to encounter a uniquely creative mind in a viscerally direct way through his own words, art, snapshots, and mementos. The archive reveals his studio as the new post-war gathering place for artists, succeeding the previous generation of artists in Fort Worth, and although his career lasted only about twenty years, and his life was cut short, he inspired and led a generation of artists that followed him and created artistic works of enduring beauty.

Notes

-

Charles Truett Williams to Mrs. C. Williams, November 19, 1945, in Correspondence - General [1] folder, Charles Truett Williams Papers, Amon Carter Museum of American Art (hereinafter, “ACMAA Williams Papers”). ↩︎

-

Louise met Charles before the war while they both attended Hardin-Simmons University, and they married in 1941. Anita was his son Karl’s grade-school teacher. They married in 1951. “Marriage License, Chas. T. Williams and Anita S. McConnell,” August 31, 1951, in Legal and Financial Records, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Father and son had an often tumultuous relationship. Karl assisted in the studio before leaving for college, but like his father, he would pursue his own course. Karl Williams, conversation with the author, April 12, 2022. It is worth noting that the only portrait sketch in the papers is that of a young Karl. ↩︎

-

Anita continued corresponding with Ménard for years after Charles’s passing. ↩︎

-

His body of work is explored in detail in Katie Robinson Edwards’s essay, but a large portion of his works were designed as architectural elements—directly, such as fountain pieces and decorative additions to structures, or indirectly through appropriation in found object designs using building materials. ↩︎

-

Charles T. Williams, “American Institute of Architects (AIA) Lecture” (unpublished manuscript, abridged), October 25, 1955, 1, in Clippings folder, ACMAA Williams Papers. ↩︎

-

Williams specifically called any artist a shaman as a way to express the nuance of an abstracted spirituality. He was raised in a Christian household but clearly did not feel the need for an anthropomorphized deity. He did not express overt disdain for others who held sincere convictions, however, and within the papers are examples of his linocut blocks that use Christian motifs and imagery for holidays. Both Karl Williams and Katie Robinson Edwards note the enmity between Umlauf and Williams, who actively detested each other both professionally and personally. Williams found Umlauf’s extensive use of religious motifs pandering and unartistic. However, Umlauf received many more commissions because he read the pulse of his patrons. Karl Williams, conversation with the author, April 12, 2022. ↩︎

-

Based on the surrealist “Exquisite Corpse” party game. ↩︎

-

The dangerous side of this force of personality is demonstrated in a story of his stepson’s getting in trouble with the police. After his son was roughly delivered to the Williams residence by the police, Charles sent him inside and, barehanded, threw the police officer off of his property. “He was incredibly strong from working in metal and stone, but his presence was what made you never want to cross him.” Karl Williams, conversation with the author, April 12, 2022. ↩︎